As the world’s biggest cattle producer, Brazil braces for change

While you’re browsing the mall for running shoes, the Amazon rainforest is probably the farthest thing from your mind. Perhaps it shouldn’t be.

The globalization of commodity supply chains has created links between consumer products and distant ecosystems like the Amazon. Shoes sold in downtown Manhattan may have been assembled in Vietnam using leather supplied from a Brazilian processor that subcontracted to a rancher in the Amazon. But while demand for these products is currently driving environmental degradation, this connection may also hold the key to slowing the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest.

The sharp contrast between forest and pasture in Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett Butler.

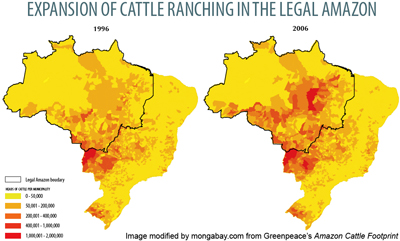

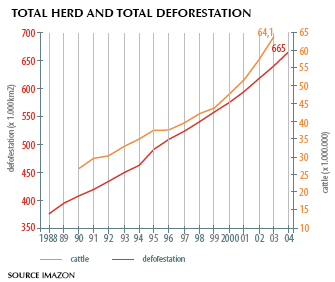

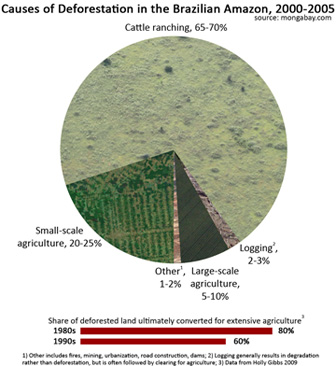

Cattle ranching is overwhelmingly the biggest driver of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: the fate of nearly 80 percent of cleared rainforest land is to serve as forage for livestock. Since 2006 more than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, an open space larger than France. The Brazilian Amazon, region consisting of rainforests and a biologically rich wooded grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle, up from 26.6 million in 1990 and equivalent to more than 85 percent of the total U. S. herd. Brazil is today the world’s largest exporter and producer of beef.

Brazilian cattle products end up in a wide array of consumer goods. Fresh beef is converted into burgers sold in fast-food restaurants and grocery stores across Brazil, Russia, Venezuela, and a number of other countries. Processed meat finds its way into canned products in Europe and America, while leather goes to China, Italy, Vietnam, and Hong Kong. But as Brazil’s beef industry has grown along with its ties to global conglomerates, so has its vulnerability.

A cattle herd wandering in the heart of Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett Butler.

The role of the cattle industry in deforestation is no secret. Environmental groups have issued reports for years warning that cattle production is the dominant driver of forest destruction, but their campaigns have had no discernible impact on deforestation. Forest clearing remains stubbornly high while beef production has continued to expand, enabling the industry to become an economic and political juggernaut, seemingly unstoppable. But in catering toward conglomerates serving an international market—part of a broader trend over the past 20 years in which industrial corporations have replaced poor farmers as the primary agents of deforestation—producers have left themselves exposed to consumer backlash. It’s tough for an environment group to target a subsistence farmer who’s clearing land to feed his family; it’s much easier to go after a multinational enterprise bent on maximizing profits by minimizing raw material costs. Thus in its strength, the multibillion dollar Brazilian cattle industry developed an Achilles’ heel—it was only a clever campaign away from facing this new reality.

This June Greenpeace leveraged this vulnerability. The green group issued Slaughtering the Amazon [PDF], a report that linked some of the world’s most prominent brands to illegal destruction of the Amazon rainforest. The fallout was immediate and substantial.

Days after the report was released, Brazil’s biggest domestic beef buyers, supermarket chains Wal-Mart, Carrefour, and Pão de Açúcar, announced they would suspend contracts with suppliers found to be involved in Amazon deforestation. Bertin, the world’s second largest beef exporter, saw its $90 million loan from the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation withdrawn. Investigators raided the offices of JBS, the world’s largest beef processor, and other firms, arresting executives for corruption, fraud, and collusion. And a Brazilian federal prosecutor filed a billion-dollar law suit against the cattle industry for environmental damage, warning that firms found to be marketing tainted meat will be subject to fines of 500 reais ($260) per kilo. Marfrig, the world’s fourth largest beef trader, said it would institute a moratorium on buying cattle raised in newly deforested areas within the Brazilian Amazon (Bertin echoed the moratorium last month). BNDES, the development bank that accounts for most financing for the agricultural sector in Brazil, announced it would reform its lending policies, making loans contingent on environmental performance.

But while the Greenpeace report effectively turned the Brazilian beef industry upside down, it was short on solutions. Banning cattle production in the Amazon is unlikely given the growing global beef demand, a demand due largely to the surging middle-class appetite for meat in the emerging economies of Brazil, China, India, and Russia. The Amazon is expected to remain a top supplier.

John Cain Carter in Mato Grosso. Photo by Woods Hole Research Center researchers. John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon. |

So is there a solution? In the immediate aftermath of the beef scandal, informed parties turned to an unlikely figure: a Texan rancher named John Cain Carter. Working in partnership with the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM), a Brazilian NGO; the Woods Hole Research Institute, a scientific center; and other groups, Carter’s organization, Alianca da Terra, has devised a unique approach to promoting land stewardship in the Amazon, one that could eventually be applied to commodity production in ecologically sensitive areas around the world.

Carter is not a conventional Brazilian or Texas rancher. After serving in the first Gulf War he married a Brazilian and ended up on the Amazon frontier in Mato Grosso, a state in the center of the South American continent. At that time, eastern Mato Grosso was a frontier in the truest sense of the word—a region where armed land invasion was rife, conflict between Indian tribes and outsiders raged, disputes were settled in blood, and law enforcement was only an abstract concept. In other words, a land without governance. The circumstances perpetuated a forest-clearing bonanza: Carter moved to the Amazon during what was perhaps the greatest spasm of forest destruction ever pursued at the hand of man. Some 205,000 sq km were destroyed between 1995 and 2004—an area larger than Nebraska. Nearly 80,000 sq km of this area was lost in Mato Grosso.

While Carter readily concedes he is no environmentalist, the carnage around him compelled him to act. He believes his approach, which is based on on-the-ground experience in one of the toughest and most violent agricultural frontiers on the planet, is the only path forward for industry and the environment.

Rainforest and cattle pasture in Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett Butler.

Why conservation has failed the frontier.

On paper, environmental laws in the Brazilian Amazon are among the world’s most stringent. Landowners are required to keep 80 percent of their land forested, but lack of law enforcement has undermined this regulation, while economics and politics have conspired to thwart efforts to slow deforestation on the Amazon frontier. For environmental groups used to working under the rule of law, success on the frontier is an enigma.

“Two of my workers were gunned down last week ,” Carter said in July. “This is not a place for NGOs to be working. It’s a place for the cavalry.”

But even the cavalry can’t be assumed to be on the same side of the law, according to Carter, who says some local officials are complicit in land-grabbing and illicit forest clearing.

Forest clearing in Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

“We have local politicians coming on the radio telling people to invade the land,” Carter said while piloting his Cessna over a patch of his reserva legal — the government-mandated forest easement— that was cut and burned in October 2007 when squatters, intent on claiming the forest and planting it with pasture grass, invaded. “When I was invaded, there was nothing I could do to convince authorities to get them out. When police finally came they refused to go into the forest. Now they are fining me for non-compliance. ”

“The problem, the irony, is that the government demands we maintain our forest reserve yet offer zero support when property rights are challenged. One of the main drivers to deforest is to maintain property rights.”

The profit potential of converting forest is too great to pass up. In a region where land prices are appreciating quickly, cattle ranching is used as a vehicle for land speculation. Forestland has little value—but cleared pastureland can be used to produce cattle or sold to large-scale farmers . It’s also more secure.

“Squatters don’t invade pasture,” Carter said.

But it is not only ranchers who face invasions—virtually any forest is at risk. For example, Marãiwatsede, the Xavante indigenous reservation neighboring John Carter’s ranch, has been invaded several times. At one point the tribe controlled only 5 percent of its 167,000 hectares—an army of invasores was busily cutting down trees in preparation for burning.

Deforestation and head of cattle in the Brazilian Amazon. Courtesy of Greenpeace. |

Squatters are often used as a proxy by development interests to gain control of land. With archaic land titling processes, irregular law enforcement, and rampant corruption at the local and state levels, it is difficult to distinguish legitimate owners of land from illegitimate ones. A “Wild West” mentality prevails and violence is common in both Mato Grosso and Para, the states at the heart of Brazil’s fast expanding agricultural frontier. Several times over the past few years—including in the aftermath of the murder of American nun Dorothy Stang and a recent uprising in Tailandia—the federal government has had to send in the army to quell dangerously escalating situations.

Still, Carter is hopeful that the situation can be improved by converting Brazil’s strict environmental codes into a marketing advantage for ranchers by guaranteeing to buyers that its certified beef is produced legally and sustainably, sometimes in excess of legal requirements. Aliança da Terra’s certification system aims to take the place of a failed governance regime by creating incentives for producers to maintain their forest reserves, reforest waterways, implement fire controls, and conserve soils. The incentive for producers is market access: Aliança certification could help Brazilian farmers and ranchers get premium prices by directly supplying major supermarkets and restaurant chains who can say they are using legally and responsibly produced beef. Consequently the program ensures that more rainforest is left standing, preserving more ecosystem services and biodiversity than would otherwise be the case.

|

“We want market recognition for shouldering this conservation burden,” Carter said. “Where else in the world do you have landowners who have to keep 50 percent of their land forest? Nowhere. As it is right now there’s nothing to keep forest standing because the law doesn’t catch you in time and you can always bribe your way out of it if you do get caught.”

But if the promise of Aliança’s certification system has helped build momentum among producers over the past year-and-a-half, the publication of Greenpeace’s report jump-started overnight a market for certified beef. Now the world’s biggest beef buyers are interested in traceability and in the credibility of a land registry for Amazon ranches. Their interest has kicked off a flurry of certification schemes, but none are as far along or have as much buy-in from producers as Aliança’s system.

“If you don’t have buy-in from landowners, you don’t have anything,” said Carter.

An unlikely advocate for the initiative is Blairo Maggi, the soy farmer-turned-governor of the Amazon state of Mato Grosso, to whom Greenpeace gave its “Golden Chainsaw award” in 2005 for being “the Brazilian person who most contributed to Amazon destruction.” Maggi now believes certification could be a ticket into more markets for Brazilian agricultural products, while payments for ecosystem services could be a lucrative means to diversify—and sustain—Amazonia’s economy. Even BNDES, the infamous funder of rainforest destruction, in mandating chain-of-custody rules for cattle producers.

|

So with demand firmly in place, suppliers have a reason to participate—they will get their access to premium markets. In fact Amazon beef is highly suited for burgers, so a buyer like McDonald’s can be assured that its products aren’t coming from deforested lands. And a partnership with scientists also has sweetened the deal for producers—reforestation along rivers and creeks may be rewarded with carbon credits, according to Dan Nepstad, a scientist at Woods Hole.

“Rabobank invested approximately $50 million in a pilot program in which ranchers reforest their riparian zone forests.” he said. “This is now being developed into a CDM program. With riparian zone restoration, carbon is sequestered and stream health will eventually improve as well.”

Researchers from IPAM and Woods Hole will be monitoring the environmental response to the program.

“There have been huge gains on the maps in terms of protected areas, but without governance these could be jeopardized. So only half the battle is been won at this point,” Carter said. “If you don’t engage the private sector, it’s never going be saved. There need to be incentives to preserve forest on private property.”

“Ranchers are tired of being demonized. If they are presented with a viable option, they can be compelled to become part of the solution.

“I think environmental groups know this now. Over the past five years NGOs have been scrambling to partner with ranchers and farmers.”

|

In a sign that interest in certification is growing, last month the Forest Footprint Disclosure Project was launched to help identify how an organization’s activities and supply chains contribute to forest destruction. The UK government-sponsored initiative will ask companies to “disclose how their operations and supply chains are impacting forests worldwide, and what is being done to manage those impacts responsibly.” Major buyers of cattle products are also joining in. Both Wal-mart and Nike announced they will require chain-of-custody certification from suppliers, and major fast-food chains are in negotiations.

But the effort to create a credible land registry in the Amazon still faces challenges. Many producers are furious with the Greenpeace report and have threatened to boycott beef buyers. While it may seem like an empty threat, Amazon beef is an export-driven industry and most beef goes to countries where environmental performance is at best a distant concern. Likewise, Brazilian shoppers haven’t shown a strong preference for the eco-credentials of products, suggesting that there remains a strong market for beef regardless of how it is produced.

However, in the aftermath of the report, and after recent public commitments to reduce emissions from deforestation under the national climate plan, the Brazilian government has expressed keen interest in improving environmental performance. Beyond that, if such schemes successfully provide a financial carrot in the form of higher prices for beef and payments for reforestation, this will encourage ranchers to become part of the system. But standards can be taken too far, becoming so burdensome for producers they drop out if incentives can’t sufficiently sweeten the deal. Gaming the system is also a possibility, especially given that BNDES is favoring the use of ear tags—which can be easily removed—for tracking cattle.

|

“In my hometown, one of the traditional centers of cattle ranching, they have a saying: ‘The cow walks, and the earrings fly,'” said Sergio Abranches, a Brazilian environmental journalist.

But Aliança has devised an alternative tracking mechanism to help prevent fraud and laundering.

“A chip or DNA tracking is much more secure than an eartag,” said Thomas Lovejoy, an Amazon expert with the H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment. “John Carter has thought long and hard about this and has done an exemplary job; indeed he has shown the way out.”

But there are grander issues in play. Brazil has committed to spending more than $320 billion on new infrastructure projects, a prospect that could negate gains from a commodity tracking system and dwarfs the $21 billion it seeks to raise for protecting the Amazon. Further, a new law, approved last month by President Lula, could outweigh the value of improved stewardship by ranchers. The law grants title to hundreds of thousands of farmers, ranchers, and squatters who have illegally occupied more than a quarter million square miles of protected forest. At present it is unclear whether the law will spur increased deforestation or bring some semblance of governance to the region, making it easier to control deforestation, but the consequences could be substantial.

|

Finally, pressure to reduce new forest clearing could spur intensification—producing more cattle on less land—which could have mixed environmental impacts. Improved pasture management could dramatically boost the productivity of Amazon cattle ranching, which is currently highly “extensive” with an average of only one cow per two-and-a-half acres. Embrapa, the agricultural ministry’s research institute, estimates that productivity could be nearly doubled by rehabilitating degraded pastureland. But intensification through use of industrial feedlots and supplemental feeding of grains could cause other headaches, including increased use of antibiotics, faster degradation of pasture, and aggregation of waste.

To some, these issues may suggest that curbing beef consumption is the ultimate solution to deforestation in the Amazon as well as other environmental problems, but in the meantime it is clear that industry will play a critical part if the tide in the Amazon is to be turned.

“The whole Amazon will be torn down if we don’t come up with a sensible and effective system,” said Carter. “The time to act is now.”

NOTE: A condensed version of this article appeared on Yale e360 last month

|

|

Related articles on cattle ranching and the Amazon rainforest

Activists target Brazil’s largest driver of deforestation: cattle ranching

(09/08/2009) Perhaps unexpectedly for a group with roots in confrontational activism, Amigos da Terra – Amazônia Brasileira is calling for a rather pragmatic approach to address to cattle ranching, the largest driver of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The solution, says Roberto Smeraldi, founder and director of Amigos da Terra, involves improving the productivity of cattle ranching, thereby allowing forest to recover without sacrificing jobs or income; establishing a moratorium on new clearing; and recognizing the economic values of maintaining the ecological functions of Earth’s largest rainforest.

Are we on the brink of saving rainforests?

(07/22/2009) Until now saving rainforests seemed like an impossible mission. But the world is now warming to the idea that a proposed solution to help address climate change could offer a new way to unlock the value of forest without cutting it down.Deep in the Brazilian Amazon, members of the Surui tribe are developing a scheme that will reward them for protecting their rainforest home from encroachment by ranchers and illegal loggers. The project, initiated by the Surui themselves, will bring jobs as park guards and deliver health clinics, computers, and schools that will help youths retain traditional knowledge and cultural ties to the forest. Surprisingly, the states of California, Wisconsin and Illinois may finance the endeavor as part of their climate change mitigation programs.

Brazil’s plan to save the Amazon rainforest

(06/02/2009) Accounting for roughly half of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2005, Brazil is the most important supply-side player when it comes to developing a climate framework that includes reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). But Brazil’s position on REDD contrasts with proposals put forth by other tropical forest countries, including the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, a negotiating block of 15 countries. Instead of advocating a market-based approach to REDD, where credits generated from forest conservation would be traded between countries, Brazil is calling for a giant fund financed with donations from industrialized nations. Contributors would not be eligible for carbon credits that could be used to meet emission reduction obligations under a binding climate treaty.

Beef consumption fuels rainforest destruction

(02/16/2009) Nearly 80 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon results from cattle ranching, according to a new report by Greenpeace. The finding confirms what Amazon researchers have long known – that Brazil’s rise to become the world’s largest exporter of beef has come at the expense of Earth’s biggest rainforest. More than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture since 1996, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, an area larger than France. The legal Amazon, an region consisting of rainforests and a biologically-rich grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle. For comparison, the entire U.S. herd was 96 million in 2008.

How to save the Amazon rainforest

(01/04/2009) Environmentalists have long voiced concern over the vanishing Amazon rainforest, but they haven’t been particularly effective at slowing forest loss. In fact, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars in donor funds that have flowed into the region since 2000 and the establishment of more than 100 million hectares of protected areas since 2002, average annual deforestation rates have increased since the 1990s, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 square miles) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004. With land prices fast appreciating, cattle ranching and industrial soy farms expanding, and billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure projects in the works, development pressure on the Amazon is expected to accelerate. Given these trends, it is apparent that conservation efforts alone will not determine the fate of the Amazon or other rainforests. Some argue that market measures, which value forests for the ecosystem services they provide as well as reward developers for environmental performance, will be the key to saving the Amazon from large-scale destruction. In the end it may be the very markets currently driving deforestation that save forests.

Corporations become prime driver of deforestation, providing clear target for environmentalists

(08/05/2008) The major drivers of tropical deforestation have changed in recent decades. According to a forthcoming article, deforestation has shifted from poverty-driven subsistence farming to major corporations razing forests for large-scale projects in mining, logging, oil and gas development, and agriculture. While this change makes many scientists and conservationists uneasy, it may allow for more effective action against deforestation. Rhett A. Butler of Mongabay.com, a leading environmental science website focusing on tropical forests, and William F. Laurance of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama believe that the shift to deforestation by large corporations gives environmentalists and concerned governments a clear, identifiable target that may prove more responsive to environmental concerns.

Future threats to the Amazon rainforest

(07/31/2008) Between June 2000 and June 2008, more than 150,000 square kilometers of rainforest were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon. While deforestation rates have slowed since 2004, forest loss is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. This is a look at past, current and potential future drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

Half the Amazon rainforest will be lost within 20 years

(02/27/2008) More than half the Amazon rainforest will be damaged or destroyed within 20 years if deforestation, forest fires, and climate trends continue apace, warns a study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Reviewing recent trends in economic, ecological and climatic processes in Amazonia, Daniel Nepstad and colleagues forecast that 55 percent of Amazon forests will be “cleared, logged, damaged by drought, or burned” in the next 20 years. The damage will release 15-26 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, adding to a feedback cycle that will worsen both warming and forest degradation in the region. While the projections are bleak, the authors are hopeful that emerging trends could reduce the likelihood of a near-term die-back. These include the growing concern in commodity markets on the environmental performance of ranchers and farmers; greater investment in fire control mechanisms among owners of fire-sensitive investments; emergence of a carbon market for forest-based offsets; and the establishment of protected areas in regions where development is fast-expanding.

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(06/06/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(06/03/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.