Although most Americans have likely seen photos and videos of the world’s largest rainforest, the Amazon, they will probably never see it face-to-face. For many, the Amazon seems incredibly remote: it is a dim, mysterious place, a jungle surfeit in adventure and beauty—but not a place to take a family vacation or spend a honeymoon. This means that the destruction of the Amazon, like the rainforest itself, also appears distant when seen from Oregon or North Carolina or Pennsylvania. Oil spills in Ecuador, cattle ranching in Brazil, hydroelectric dams in Peru: these issues are low, if not non-existent, for most Americans. But a visit to the Amazon changes all that.

This was recently confirmed to me when I traveled with American college students during a trip to far-flung Yasuni National Park in Ecuador. As a part of a study abroad program with the University of San Francisco in Quito and the Galapagos Academic Institute for the Arts and Sciences (GAIAS), these students spend a semester studying ecology and environmental issues in Ecuador, including a first-time visit to the Amazon rainforest at Tiputini Biodiversity Station in Yasuni—and our trips just happened to overlap.

The Tiputini River in Yasuni National Park just outside Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

Seeing this as a rare opportunity, I spent mealtimes picking the students’ brains. Finding them incredibly intelligent and globally-aware, I delighted in listening to their views on rainforest conservation, indigenous rights, and the oil industry, and learning from them about local issues, ecology, and history. I also had the pleasure of watching them react to experiencing the Amazon for the first time, reminding me just how fortunate our small band was. At some point, I realized that these students would not only inherit the world’s worsening environmental problems (most will be only 60 by the time 2050 rolls around), but they have also been largely left out of the on-going debate over deforestation, climate change, and other environmental issues. I thought it was time for the inheriting generation to weigh-in about their experiences and opinions.

Yasuni National Park proved a perfect setting—as efforts to save the park have produced one of the most experimental ideas in conservation-history. With the support of the UN, Ecuador is asking industrialized nations to pay it to keep nearly a billion tons of oil in the ground, saving a sizeable chunk of Yasuni from development and mitigating global climate change. Dubbed, the Yasuni-ITT Initiative (after the bloc it would protect), Ecuador would receive $3.6 billion dollars over the next 13 years, about half the income that the oil would bring in. If successful the agreement will prevent some 410 million tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere and conserve arguably the most biodiverse place on Earth.

Bold, controversial, and fragile, the agreement is at the cutting edge of efforts to fight climate change, save biodiversity, develop sustainably, and preserve threatened ecosystems for future generations. It was the perfect plot from which to explore the region’s and world’s environmental issues with a group of intrepid students.

In an October 2010 interview, mongabay.com spoke with five undergraduate students attending the University of San Francisco, Quito and the Galapagos Academic Institute for the Arts and Sciences (GAIAS) study abroad program about their first impressions of the Amazon, their opinion of the Yasuni-ITT Initiative, and what they see as the environmental challenges for their generation.

Now, I’ll let them speak for themselves:

INTERVIEW WITH THE UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS

Mongabay: Tell me about your first impression of the Amazon rainforest?

Michael Huffaker with a stick insect at Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Huffaker is 20, and is majoring in Biology at Juniata College in Pennsylvania. |

Michael Huffaker: Well that’s a doozy of a first question. When we flew in it was pretty foggy so I couldn’t see much from the plane. We took a bus to the boat dock and so far it looked pretty much like a regular small tow—HOLY CRAP IT’S A MONKEY!!!

From then on the new things didn’t stop. I remember thinking things like “That’s a really big tree…no wait, THAT’S a big tree.” The trees were like things from The Jungle Book, giant trees with vines hanging off of them. The river was huge, and our whole trip to the biodiversity station was like being in a real life magic forest (my cousin and I would pretend our parents’ gardens were magic forests—the Amazon was like how our imaginations thought of those gardens, except it was real). So basically I spent a lot of time convincing myself that I wasn’t watching a documentary and that I was actually in the jungle.

Trevor Probert: Navigating through the Tiputini River gave me two connected emotions: one of excitement, the other of concern. I felt as if this place was an immense fortress of biological treasure, but I simultaneously couldn’t help but be disturbed by my understanding that incredible places similar to Tiputini are lost everyday.

Krista Leibensperger: My first impression came when we were on the boat headed down the Tiputini River. The sun was shining and the sky was almost the bluest I’ve ever seen it. The contrast between the bright green of the trees, the blue of the sky, and the brown water of the river reassured me that this place was still untouched, that it was still pristine and perfect.

Mongabay: You’ve seen photos, shows, movies about the Amazon. How does the real thing compare?

Amy Jazwa: The Amazon is the most enchanting, enlivening place I have ever traveled to. Ever since I was a young child, I had dreams of traveling to the Amazon Rainforest. I admired the beauty of the incredible number and types of species that existed in the Amazon. Receiving the opportunity to travel to this mystical place I will appreciate for the rest of my life. Depictions of the Amazon in National Geographic or on Discovery Channel gave no justice to the grandeur of this amazing ecosystem. I would have gladly stayed at Tiputini Biodiversity Station for weeks to be able to fully experience the jungle.

One thing that did surprise me was the reality of the detrimental actions that are harming the rainforest. Flying over the Amazon Rainforest on our way to Tiputini, I could see some clear cuts of the forest that are terribly detrimental to the forest. As we floated down the river, I could see oil drilling contraptions that so obviously disrupt the ecosystem by disturbing the natural stability of the forest floor and change the landscape because of the roads that are being built to access the oil. These two examples occurred in the span of two hours and made me realize how prevalent ecosystem damaging activities are in the Amazon.

Krista Leibensperger near Quito, Ecuador. Leibensperger is 20 and is majoring in Environmental Science at Juniata College. |

Michael Rudolph: I think things seem a lot less exotic when they are not being narrated by David Attenborough. I am from the Pacific Northwest, and I was actually reminded a little of our coastal forests, if I could get past the individual species. When I am hiking in the U.S. I know that there are potentially bears and cougars in the area, but I have never seen any. The Amazon was the same; we knew there were jaguars, wild dogs, tapirs and a million other things, but they weren´t jumping out at every turn.

One huge difference was the sounds. It was extremely loud 24 hours a day, but mostly from frogs, birds and insects and the occasional howler monkey call. Monkeys were definitely another big difference. They have always been mysterious animals to me, but it is amazing how fast you get accustomed to seeing them. All things considered, I felt very at home, even if the reality was that it was nothing like where I live.

Krista Leibensperger: Nothing can ever really compare to the real thing. Photos and movies are a good visual representation, but actually being in the middle of a huge rainforest, where you can’t see the ground from up in the canopy, where you can stand next to huge buttressed roots and even climb inside of a hollow tree, where you can hear, see, smell, and sometimes even taste everything around you is an experience that nothing can ever compare to.

Mongabay: What is your best memory from Yasuni?

Michael Huffaker: Floating down the Tiputini River in life jackets. It was amazing. The water was not only lovely but I got to spend a lot of time with friends and got to see a lot of wildlife. I remember we looked up and saw a group of big monkeys leaping through the trees, one swung on a vine. It was great.

Amy Jazwa exploring a tree at Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Jazwa is 21; she is majoring in Biology and minoring in Chemistry and Medical Anthropology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. |

Amy Jazwa: One morning after my group ate breakfast, we were given a break before we began our activities for the day. I grabbed my camera out of the dry box in an attempt to take pictures of the station. I ran into one of our forest guides, Mayer, who was an amazing guide and person. The day before he had taken us on a fabulous hike throughout the forest, explaining ecosystem interactions, pointing out amazing species, and telling wonderful stories. On this occasion, Mayer saw my camera and beckoned me to follow him. We began walking around the small cleared square of forest where our cabins were standing and in just 5 minutes Mayer had already pointed out at least 8 different insect species for me to observe. We walked around the clearing for about an hour, observing insects and plant species that were on the outskirts. I had never seen so many different and amazing species in such a short period of time! What made this stroll even better was the fact that Mayer explained everything to me in Spanish and I felt as if I gained a greater connection to the forest because I was learning about everything in the regional language.

Mongabay: What was your favorite species sighting?

Michael Rudolph: Definitely the river dolphins, even though we only caught a few glimpses. It was amazing to think that such complex animals could be living in a tiny, murky river when even enormous rivers back home have only fish and the occasional sea lion that swims up from the coast. I can totally see why sailors were mystified by dolphins back in the day. I still am.

Amy Jazwa: My favorite species sighting was of monkeys. We were in an observation tower in a humongous ceiba tree and in the distance a woolly monkey was lazy napping on a tree branch. A few minutes later he awakens and begins to travel about the tree. Then from some lower branches the rest of the troop travels to the first monkey and I was able to observe interactions of this family of about seven monkeys. I learned from a classmate that traveled to the tower later that they observed the exact same troop of monkeys and their first spotting of the troop was of one of the monkeys lazily napping in the tree!

Trevor Probert: While in the bird-watching canopy tower, we sighted two paradise tanagers. These birds are very brightly colored, very small, very fast and difficult to get a good look at, however two paradise tanagers decided to rest on the top of a neighboring tree giving us the perfect opportunity to view them. The excitement of [our professor] David Romo and our guide Mayor seeing these two birds is a memory that will stay with me forever, as if their excitement was transmitted directly into myself.

CONSERVATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

Mongabay: What is your view of the Yasuni-ITT initiative?

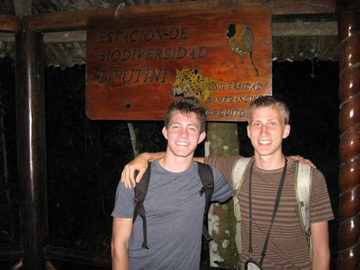

Michael Rudolph (right) and Trevor Probert (left) in Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Rudolph is 19. He is majoring in Englsih and minoring in Biology at Southern Oregon University. Probert is 21. He is majoring in Geography and Environmental Studies at the University of Oregon. |

Michael Rudolph: I have been daydreaming about [the Yasuni-ITT initiative] saving the world. One of the main things that I took away from the lecturers at the Tiputini Biodiversityt Station was the complexity of conservation issues, and that is why I am half-scared of this whole section of questions, but I am willing to share my Yasuni-ITT fantasy. It goes something like this: [President of Ecuador] Raffael Correa gets his quota of carbon sequestering donations, and Yasuni National Park is saved from oil exploitation. The system is then adopted around the developing world, and oil is left in the ground as the ecosystems above it are saved. The revenue donated to these countries is used for bettering the services available for their people and for the reforestation of areas already damaged by non-sustainable exploitation. Meanwhile, in the UN, the greenhouse gas emission caps are steadily lowered, stimulating the development of alternative energy technologies, and ensuring that the demand for Yasuni-ITT type carbon credits does not disappear. The world is renewed as we develop the technology we need to live here without destroying it.

Krista Leibensperger: I believe that this is a huge step forward for conservation, even bigger if it actually works, which hopefully it will. But the ITT initiative, while it is trying to protect one of the most productive areas on earth, just allows us to shift the problem, we are still polluting just as much in other countries. But hopefully this will work and then we can tackle other areas and keep them alive and healthy.

Trevor Probert: While I agree with the outcome of protecting the forest, and all in all [the Yasuni-ITT initiative] is probably the most innovative and strategic plan of its kind, I will always insist that the need to protect and conserve the forest, or our global environment for that matter, should be derived from an intrinsically valued necessity rather than through possibilities of economic gain. While the initiative can successfully save this section of the forest, I critique it because it reinforces the wrong values. We should protect the Amazon because we have an intrinsic care for the life harbored within the Amazon, not because we have found a more economically profitable manner of exploiting the forest (in a physical or symbolic sense).

Mongabay: Why do you think it’s important to conserve places like Yasuni?

Michael Huffaker: From a biological perspective, areas like Yasuni are a goldmine for new information. The amount of medicine and other modern conveniences based on plants, animals, and other organisms from such areas is astounding, and our understanding of life itself has depended greatly on places like Yasuni.

Aside from the benefits that we can gain from the forest, it’s an ecosystem unlike any other. The spectrum of life in the Amazon rainforest is a fantastic illustration of the beauty of life and the forces that shape it. Where else in the world can one go and see ten species of trees in 20 square feet? It’s unbelievable, and just freaking cool.

Trevor Probert: Because Yasuni, like any other place of earth, represents life and community. Yasuni just happens to be more biologically diverse than other places, which means that it harbors even more life than other geographic locations. This single factor makes Yasuni very special and unique; to conserve the Yasuni is to preserve an interconnected community of species found nowhere else.

But we can even extend the conservation value of the Yasuni to humans. There are indigenous peoples living within the Amazon forest who are dependent on the forest. These people are extremely important because they hold knowledge that no one else has; to destroy the forest is to destroy these peoples and all the knowledge they have. In a world where we a progressively separating ourselves from the environment, we will soon realize how important it is to live with, not against the environment. Our livelihoods our dependent on the quality of the environment, and the indigenous people living within/around Yasuni, or places similar to Yasuni, are some of the only remaining humans with the knowledge of living with the environment. To conserve Yasuni is to conserve the opportunity for western culture to relearn the knowledge that has been gradually dissolved ever since the beginning of civilization.

Mongabay: Your generation unfortunately has inherited a perfect storm of global environmental issues. What do you see as the biggest environmental concerns for your generation?

Trevor Probert looking for wildlife on the lake. |

Krista Leibensperger: Exactly as the question states there is a “perfect storm” and everything is equally as important. If I had to choose one issue to work on however, I believe it would be the deforestation of the tropical rainforest.

Michael Huffaker: Many of the global environmental issues are interconnected, but I see global climate change as the most pressing issue. Unfortunately this is also the issue that will take the largest scale movement to work against.

Alternative fuel sources seem to be a logical choice, and taking the pressure off of fossil fuels would also help relieve the pressure on places like Yasuni.

Amy Jazwa: One of the biggest concerns for the environment is the exponentially increasing population. Because the population keeps growing at an obscene rate, resources are going to be used up probably faster than we can predict. And what is important is not the fact that humans will run out of resources, it is that these resources are Mother Earth. We are destroying forests, polluting waters, diminishing water tables, driving species rapidly to extinction all for human consumption and with little care for the fact that ecosystems are fragile and often take hundreds of years to recover.

It is crucial to promote family planning education around the world in order to help stabilize population growth. If the population continues to grow at its current rate, it is hard to imagine the future in an optimistic light either for humans and the rest of the species on the Earth.

Mongabay: Has your time in the Amazon, and Ecuador in general, changed your opinion of environmental issues in the United States?

Michael Rudolph: Since I have been in Ecuador I have felt a little closer to the ‘end of the world’, and I think that a healthy dose of that point of view could go a long way in the United States. We´re beyond the ability of politicians and legislative processes to save us, and we don´t need them. In the United States we are very capable of changing the way we live right now.

Krista Leibensperger: My time here has definitely opened my eyes to the major environmental issues of other countries. I used to think that the United States was one of the few countries with major environmental issues, simply because I didn’t know about other environmental issues. Now I think that while we do need to do something about the environmental issues in the United States, there are other, possibly more important, areas to conserve, and maybe we can prevent these areas from becoming industrialized.

Mongabay: What can you do to ensure that places like Yasuni will still be around for future generations?

Biodiversity bonanza: butterfly in Yasuni National Park (this species hasn’t been identified). Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

Amy Jazwa: One of the most important aspects of conservation is education. I am a firm believer that promoting awareness and educating people on issues in the most non-biased manner possible is an extremely effective gateway to conservation. From traveling to the Amazon, I gained firsthand experience about the importance of this ecosystem. Protecting the rainforest is important for more than just the species in the rainforest—ecosystems throughout the world are interconnected in ways we don’t fully understand yet.

When I go back home, I will be sure to share my stories about the amazing complexity of the rainforest and the importance of the incredible diversity that it holds. I hope that even my spreading my stories to a small group of people will lead to a better understanding of the need to protect the rainforest.

Michael Huffaker: Things are going the way they are because, in my very simplified opinion, the world is driven by money. It makes sense, money gets us things that we need and that we want. I myself am quite a fan of money. Unfortunately many people do not see places like Yasuni as worthwhile protecting. I’m sure that most people agree that the rainforest is a nice place, but it’s difficult to incite change.

I myself see things from a biological perspective in which the rainforest is like winning the lottery in terms of potential knowledge, but it’s not reasonable to expect a politician who’s studied law and policy their entire lives to see things in exactly the same way.

So what can we do? We need to start pushing for more environmentally friendly policies. I’m not saying we all need to live 100% waste-free sustainable lives, while that’s a nice fantasy it isn’t practical. What we can do is work to reduce our impact on the environment and to develop better strategies of replacing what we’ve already taken. For example, putting resources into finding energy sources that are alternatives to fossil fuels is a good first step. Nuclear power isn’t perfect or waste-free, but compared to the amount of waste per amount of power produced it’s much cleaner. If we can continue this trend hopefully we can move closer to “clean” energy. We should also do our best to come up with more ideas like the Yasuni-ITT initiative. Plans that protect the environment and don’t require huge, instant policy shifts from large corporations (let’s face it, that just doesn’t happen very often).

Michael Rudolph: A couple of weeks after we left Tiputini we were guitar shopping for a couple of our classmates when the sales clerk tried to get us interested in an Ecuadorian made guitar, made from “very special wood.” Our red flags went up, and she continued to explain that it was from the Amazon.

The most important thing anyone can do to ensure the conservation of places like Yasuni is to be aware of where there products come from, especially oil. Personally, after learning of the history of oil exploitation in Ecuador and seeing first hand what is at stake, I don´t think I will ever set food in a car or airplane again without thinking twice.

Trevor Probert: I wish I knew [how to save Yasuni]. If I knew, I would do it immediately. Unfortunately, the problem lies on a grander scale. We need to change the fundamental values of our culture in order to ensure that any resource rich region can possibly remain for future generations.

While the Yasuni ITT initiative looks attractive and promising now, once oil resources become scarcer and scarcer in the world, there is not a single conservation-oriented force that can stop the Yasuni from being drilled for oil. The price of oil will eventually rise, and powerful economic/political forces will do everything they can to allow the oil resources to be pumped from the ground. The Yasuni ITT initiative is based on western economics, and ultimately western economics will always be exploitative and consumptive.

I will say it again: the problem can only be solved if we change the fundamental values of society.

College students with the University of San Francisco in Quito and the Galapagos Academic Institute for the Arts and Sciences (GAIAS) study abroad program seeking for wildlife on a lake near Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Amy Jazwa is second from the right. Trevor Probert is third from the right. Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

Related articles

A look at Ecuador’s agreement to leave 846 million barrels of oil in the ground

(09/13/2010) Ecuador’s pioneering initiative to voluntarily leave nearly a billion barrels of oil under Yasuní National Park, an Amazonian reserve that is arguably the most biodiverse spot on Earth, took a major step forward in early August when the government signed an accord with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for the long-awaited establishment of a trust fund. The signing event generated a wave of international media attention, but there has been very little scrutiny of what was actually signed. Here we present an initial analysis of the signed agreement, along with a brief discussion of some of the potential caveats. Due to the precedent-setting nature of this agreement, attention to the details is now of the utmost importance.

Bold rainforest idea makes good: Ecuador secures trust fund to save park from oil developers

(08/03/2010) In what may amount to a historic moment in the quest to save the world’s rainforests and mitigate climate change, Ecuador and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDF) have created a trust fund to protect one of the world’s most biodiverse rainforests from oil exploration and development. The fund will allow the international community to pay Ecuador to leave an estimated 850 million barrels of oil in Yasuni National Park in the ground instead of extracting it. This first-of-its-kind agreement, known as the Yasuni-ITT Initiative, will allow the rainforest protected area to remain pristine: preserving one of the most species-rich places on Earth, safeguarding the lives of indigenous people, and keeping an estimated 410 million tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

Oil devastates indigenous tribes from the Amazon to the Gulf

(07/27/2010) For the past few months, the mainstream media has focused on the environmental and technical dimensions of the Gulf mess. While that’s certainly important, reporters have ignored a crucial aspect of the BP spill: cultural extermination and the plight of indigenous peoples. Recently, the issue was highlighted when Louisiana Gulf residents in the town of Dulac received some unfamiliar visitors: Cofán Indians and others from the Amazon jungle. What could have prompted these indigenous peoples to travel so far from their native South America? Victims of the criminal oil industry, the Cofán are cultural survivors. Intent on helping others avoid their own unfortunate fate, the Indians shared their experiences and insights with members of the United Houma Nation who have been wondering how they will ever preserve their way of life in the face of BP’s oil spill.

Photos: park in Ecuador likely contains world’s highest biodiversity, but threatened by oil

(01/19/2010) In the midst of a seesaw political battle to save Yasuni National Park from oil developers, scientists have announced that this park in Ecuador houses more species than anywhere else in South America—and maybe the world. “Yasuní is at the center of a small zone where South America’s amphibians, birds, mammals, and vascular plants all reach maximum diversity,” Dr. Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland said in a press release. “We dubbed this area the ‘quadruple richness center.'”

Photos: expedition in Ecuador reveals numerous new species in threatened cloud forest

(01/14/2010) An expedition into rainforests on Ecuador’s coast by Reptile & Amphibian Ecology International (RAEI) have revealed a number of possible new species including a blunt-snouted, slug-eating snake; four stick insects; and up to 30 new ‘rain’ frogs. The blunt-snouted snake, which feeds on gastropods like slugs, is especially interesting, as its closest relative is in Peru, 350 miles away. In addition, a fifteen-year-old volunteer with the organization found a snake that specializes on snails. The researchers are unsure of this is a new species: the closest similar snake is 600 miles away in Panama.

Ecuador to be paid to leave oil in the ground

(12/23/2009) Ecuador will establish a trust fund for receiving payments to leave oil reserves unexploited in Yasuni National Park, one of the world’s most biodiverse rainforest reserves, reports the UN Development Programme, the agency that will administer the fund.

Ecuador’s Rafael Correa: Copenhagen Climate Hero or Environmental Foe?

(12/14/2009) As climate change negotiations continue full force in the Danish city of Copenhagen, Latin American countries are hoping the Global North will commit to its “climate debt” by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and providing resources to poor nations. It’s certainly an understandable aspiration: Latin America only produces five per cent of global emissions of carbon dioxide, a chief greenhouse gas, yet the region has borne the brunt of extreme weather ranging from droughts to flooding.

Will Ecuador’s plan to raise money for not drilling oil in the Amazon succeed?

(10/27/2009) Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park is full of wealth: it is one of the richest places on earth in terms of biodiversity; it is home to the indigenous Waorani people, as well as several uncontacted tribes; and the park’s forest and soil provides a massive carbon sink. However, Yasuni National Park also sits on wealth of a different kind: one billion barrels of oil remain locked under the pristine rainforest.

Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon

(09/13/2009) The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call “one of the most species diverse forests in the world”—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest.

Amazon tribes have long fought bloody battles against big oil in Ecuador

(09/03/2009) The promotional efforts ahead of the upcoming release of the film Crude have helped raise awareness of the plight of thousands of Ecuadorians who have suffered from environmental damages wrought by oil companies. But while Crude focuses on the relatively recent history of oil development in the Ecuadorean Amazon (specifically the fallout from Texaco’s operations during 1968-1992), conflict between oil companies and indigenous forest dwellers dates back to the 1940s.