Sometime around 2050 researchers estimate that the global population will level-out at nine billion people, adding over two billion more people to the planet. Since, one billion of the world’s population (more than one in seven) are currently going hungry—the largest number in all of history—scientists are struggling with how not only to feed those who are hungry today, but also the additional two billion that will soon grace our planet. In a new paper, published in Science, researchers make recommendations on how the world may one day feed nine billion people—sustainably.

Obstacles

The difficulties are many and large, according to the paper: “growing competition for land, water and energy, and the over-exploitation of fisheries, will affect our ability to produce food, as will the urgent requirement to reduce the impact of the food system on the environment.”

The finiteness of arable land and freshwater will be further strained by what the authors call “higher purchasing power”, which increases the demand in the developing world for “processed food, meat, dairy and fish, all of which adds pressure to the food supply system.”

Soy and forest in the Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Further complicating the problem of limited—and over-stretched resources—will be the need to adapt to a changing climate.

“Projections of food needs over the next 40 years have generated deep concern about how agricultural production can increase sufficiently in the face of climate change threats,” explains co-author Dr. Camilla Toulmin from the International Institute for Environment and Development. “Not only will rising temperature and shifts in rainfall patterns render crop production more uncertain in many areas, but the agricultural sector will need to become a better sink for carbon, through sequestration, while reducing emissions of greenhouse gas such as nitrous oxide, which is produced from use of chemical fertilizers.”

She adds that the availability of arable land is further constrained by the “need to maintain and improve the carbon stores held in forests, which also contribute to the world’s water balance, biological and cultural diversity, so expansion of farming into forest and grazing lands is not a sensible option.”

Given all of these issues, the authors conclude that “a three-fold challenge now faces the world: match the rapidly changing demand for food from a larger and more affluent population to its supply; do so in ways that are environmentally and socially sustainable; and ensure that the world’s poorest people are no longer hungry.”

Simply impossible?

The problem appears insurmountable, but the authors say that with ‘radical’ changes worldwide it is possible to feed nine billion people without destroying the environment that makes such agriculture possible.

Tea workers in Uganda. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

First the authors say that the ‘yield gap’ must be closed, in other words producing the most possible food from the land already under cultivation. Increasing yield depends on “the capacity of farmers to access and use, among other things, seeds, water, nutrients, pest management, soils, biodiversity, and knowledge,” the authors write.

Noting that farmers around the world are constrained by lack of “access to the technical knowledge and skills required to increase production, to the finances required to invest in higher production […] or to the crop and livestock varieties that maximize yields,” the authors argue that governments and institution must work to give greater and easier access for farmers—especially in the developing world—to the tools needed to increase yields. Investment is especially needed in the world’s poorest countries to aid small farmers, including reaching out specifically to women agriculturalists, to increase yields and thereby income.

The authors also recommend pushing production limits. To do so agriculture must emulate the green revolution by developing new strains of crops that are more disease resistant, require less water, and produce more food. Furthermore, they argue that corporations must make genetically-modified (GM) crops widely available, while still maintaining competitiveness. Of course, the use of GM crops remains very controversial.

“Our view is that GM is a potentially valuable technology whose advantages and disadvantages need to be considered rigorously on an evidential, inclusive, case-by-case basis: that it should neither be privileged nor automatically dismissed,” the authors write.

Rice fields in Luang Prabang province in Laos. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Reducing food waste would also go a long way in feeding the world. According to the paper, 30-40 percent of the world’s food is lost to waste. For example, a recent study found that Americans threw away enough food every day to feed an extra 200 million people.

The authors point out that the problem of wasted food in the industrialized world is complex.

“Food is at present relatively cheap, at least for these consumers, which reduces the incentives to avoid waste. Consumers have become accustomed to purchasing foods of the highest cosmetic standards and hence retailers discard many edible yet only slightly blemished products.” In addition: “the food service industry frequently uses ‘supersized’ portions as a competitive lever, while ‘buy one get one free’ offers have the same function for retailers. Litigation and lack of education on food safety has lead to a reliance on ‘use by dates’ whose safety margins often mean that food fit for consumption is thrown away.”

Waste also occurs in the developing world, but for different reasons: here “losses are due mainly to the absence of food chain infrastructure, and to lack of knowledge or investment in storage technologies on the farm,” according to the paper.

The authors recommend that in the developing world investment is needed for better transportation and storage related to food. For the industrialized world, education, advocacy, legislative changes, and cultural shifts are required to stem the massive amounts of wasted food.

In addition to increasing yields and reducing waste, the authors suggest society lessens meat consumption overall, while ensuring that livestock is raised efficiently. In regards to marine foods, the authors suggest increasing aquaculture, while at the same time working to mitigate the practices’ environmental impacts. For example, they suggest aquaculture should focus on raising marine species lower on the food chain.

Final piece: sustainability

Village and rice plots in Madagascar’s Central Plateau. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Of course, none of these shifts will matter if agriculture cannot be sustained environmentally over the long-term. The authors write that threats to sustainability from agriculture include “the release of greenhouse gases (especially methane and nitrous oxide […]); environmental pollution due to nutrient run-off; water shortages due to over-extraction; soil degradation and the loss of biodiversity through land conversion or inappropriate management; and ecosystem disruption due to the intensive harvesting of fish and other aquatic foods.”

To ensure sustainability the authors say that better ‘metrics of sustainability’ are first needed to evaluate the efficacy of strategies. According to the paper, sustainability need not threaten food security: studies have shown that sustainable farming does not mean reduced yields, in fact in many case studies employing sustainable practices actually increased yields.

“There is no simple solution to feeding sustainably nine billion people, especially as many become increasingly better off and converge on rich-country consumption patterns. A broad range of options, including those we discuss here, needs to be pursued simultaneously,” the authors conclude. “We are hopeful about scientific and technological innovation in the food system, but not as an excuse to delay difficult decisions today.”

Citation: H. Charles J. Godfray, John R. Beddington, Ian R. Crute, Lawrence Haddad, David Lawrence, James

F. Muir, Jules Pretty, Sherman Robinson, Sandy M. Thomas, Camilla Toulmin. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science. 28 January 2010. 10.1126/science.1185383.

Related articles

Cheerios maker linked to rainforest destruction

(01/19/2010) An activist group linked General Mills to destruction of rainforests in Southeast Asia in dramatic fashion on Tuesday, when it unfurled a giant banner, reading “Warning: General Mills Destroys Rainforests”, outside the company’s Minneapolis headquarters building.

Indonesian government report recommends moratorium on peatlands conversion

(01/19/2010) A study issued by Indonesian government recommends a moratorium on peatlands conversion in order to meet its greenhouse gas emissions target pledged for 2020, reports the Jakarta Post. The report, commissioned by the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), says that conversion of peatlands accounts for 50 percent of Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions but only one percent of GDP. A ban on conversion would therefore be a cost-effective way for the country to achieve its goal of reducing carbon emissions 26 percent from a projected baseline by 2020. But the recommendation is likely to face strong resistance from plantation developers eager to expand operations in peatland areas. Last year the Agricultural Ministry lifted a moratorium on the conversion of peatlands of less than 3 meters in depth for oil palm plantations. Environmentalists said the move would release billions of tons of carbon dioxide.

Amazon cattle ranching accounts for half of Brazil’s CO2 emissions

(12/12/2009) Cattle ranching accounts for half of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions according to a new study led by scientists from Brazil’s National Space Institute for Space Research (INPE).

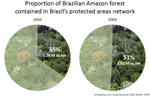

Brazil could halt Amazon deforestation within a decade

(12/03/2009) Funds generated under a U.S. cap-and-trade or a broader U.N.-supported scheme to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and degradation (“REDD”) could play a critical role in bringing deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon to a halt, reports a team writing in the journal Science. But the window of opportunity is short — Brazil has a two to three year window to take actions that would end Amazon deforestation within a decade.

Americans throw away enough food every year to feed 200 million adults

(11/30/2009) The amount of food Americans throw away has risen by approximately 50 percent since 1974 according to a new study in PLoS ONE. American now waste on average 1400 calories per person everyday, equaling 150 trillion calories a year nationwide. Considering that the average person requires approximately 2,000 calories a day, this means that the US could feed over 200 million adults every year with the food that ends up in the trash. Currently, the UN estimates that one billion people—an historical record—are going hungry worldwide.

200 million more people going hungry

(10/26/2009) The war on hunger is becoming a rout—and we’re losing. The UN World Food Program (WFP) announced today that during the last two years 200 million more people are going hungry.

Brazilian beef giants agree to moratorium on Amazon deforestation

(10/07/2009) Four of the world’s largest cattle producers and traders have agreed to a moratorium on buying cattle from newly deforested areas in the Amazon rainforest, reports Greenpeace.

(09/24/2009) With the world facing a variety of crises: climate change, food shortages, extreme poverty, and biodiversity loss, researchers are looking at ways to address more than one issue at once by revolutionizing sectors of society. One of the ideas is a transformation of agricultural practices from intensive chemical-dependent crops to mixing agriculture and forest, while relying on organic methods. The latter is known as agroforestry or land sharing—balancing the crop yields with biodiversity. Shonil Bhagwat, Director of MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management at the School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford, believes this philosophy could help the world tackle some of its biggest problems.

Brazil may ban sugarcane plantations from the Amazon, Pantanal

(09/18/2009) Brazil will restrict sugarcane plantations for ethanol production from the Amazon, the Pantanal, and other ecologically-sensitive areas under a plan announced Thursday by President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s administration, reports the Associated Press.

Kenya’s pain: famine, drought, government ambivalence cripples once stable nation

(09/17/2009) Kenya was once considered one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s success stories: the country possessed a relatively stable government, a good economy, a thriving tourist industry due to a beautiful landscape and abundant wildlife. But violent protests following a disputed election in 2007 hurt the country’s reputation, and then—even worse—drought and famine struck the country this year. The government response has been lackluster, the international community has been distracted by the economic crisis, and suddenly Kenya seems no longer to be the light of East Africa, but a warning to the world about the perils of ignoring climate change, government corruption, and the global food and water shortages.

Guatemala latest country to declare food crisis: nearly half a million families face food shortages

(09/10/2009) The President of Guatemala, Alvaro Colom, has announced a “state of public calamity” to tackle food shortages throughout the Central American nation. The failure of bean and corn crops from drought, which cut the yields of these staple crops in half, has brought the crisis to a head. In addition, prime agricultural land in Guatemala is often used to grow export crops like coffee and sugar rather than staples.

Trees sprout across farmland worldwide

(08/26/2009) Half the planet’s farmed landscapes have significant tree cover, reports a new satellite-based study. The research, conducted by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research’s World Agroforestry Centre found that tree cover exceeds 10 percent on more than 1 billion hectares of farmland, indicating that agroforestry is a “vital part” of worldwide agricultural production. 320 million hectares of forested agricultural land are found in Latin America, 190 million hectares in sub-Saharan Africa and 130 million hectares in Southeast Asia.

Unique acacia tree could play vital role in turning around Africa’s food crisis

(08/24/2009) Scientists have discovered that an acacia tree, long used by farmers in parts of Africa, could dramatically raise food yields in Africa. The acacia tree Faidherbia albida, also known as Mgunga in Swahili, possesses the unique ability to provide much-needed nitrogen to soil.