As a child I read about the near-extinction of the American bison. Once the dominant species on America’s Great Plains, I remember books illustrating how train-travelers would set their guns on open windows and shoot down bison by the hundreds as the locomotive sped through what was left of the wild west. The American bison plunged from an estimated 30 million to a few hundred at the opening of the 20th century.

When I read about the bison’s demise I remember thinking, with the characteristic superiority of a child, how such a thing could never happen today, that society has, in a word, ‘progressed’.

Grown-up now, the world has made me wiser: last month the international organization CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) struck down a ban on the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna. The story of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is a long and mostly irrational one—that is if one looks at the Atlantic bluefin from a scientific, ecologic, moral, or common-sense perspective.

School of bluefin tuna. Photo courtesy of: NOAA. |

Since 1970 the Atlantic bluefin tuna’s population has dropped by 80 percent due, like the bison, to one reason: overharvesting. Classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List, the ‘management’ of the tuna has long been in the hands of an organization known as ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas), yet the organization has continuously ignored the advice of its own scientists. For years, when researchers would come up with a fishing quota based on population estimates, ICCAT would double it. On top of that widespread illegal fishing year-after-year worsened the fish’s situation. Last year, ICCAT’s scientists for the first time recommended a total ban on Atlantic bluefin tuna fishing. But again, ICCAT ignored their own advice and instead set a quota of 13,500 tons.

After ICCAT’s repeated failures—and the tuna’s continuing decline—the duty now fell to world nations, through the organization CITES, to bring sense to the free-of-all, which, if allowed to continue, would lead to complete a population crash and quite possible extinction for the embattled fish. But last month CITES failed to garner the two-thirds majority needed to pass the ban: the vote lost soundly with 20 voting for a ban, 68 voting against, and 30 nations abstaining.

The reason? Greed. The fish is worth a lot, at least to one country. Three-fourths of the catch is shipped to Japan for sushi, and the scarcer the Atlantic bluefin tuna becomes—i.e. the closer it is to the brink of existence—the more money a single fish is worth. Currently, the Atlantic bluefin tuna trade is estimated at 7 billion US dollars a year with just one fish fetching up to 100,000 US dollars on the market. The CITES vote shows that when greed demands extinction, we have yet to stifle its siren sound.

A caught bluefin. Photo courtesy of: NOAA. |

But it’s not just the Atlantic bluefin tuna that CITES failed. Numerous species of sharks caught-up in the ‘finning’ trade were also left unprotected.

Humans, like all species, consume, yet unlike most other species we also waste—and the greater our population becomes the more we are willing to waste. In the case of ‘shark finning’, sharks are caught around the world, their fins chopped off, and then the shark itself is thrown back into the water to die. It’s a gruesome, barbaric process, but most of all it is startlingly wasteful: sharks are thrown overboard simply because their meat is not worth enough for fishermen to keep. All this death and waste is left unchecked in order to produce vast quantities of the Asian delicacy (barely a ‘delicacy’ anymore)—’shark-fun soup’—for the wealthy in China and Japan. It is estimated that 26 to 73 million sharks are killed every year for their fins alone.

Not surprisingly, this trade has helped sink shark populations worldwide. In just 15 years sharks have been devastated in the Mediterranean and the Gulf of Mexico: with a 90 percent drop in populations. Some shark species in the Mediterranean have plunged by 97 percent. But the decline is also global: shark populations have dropped by 75 percent in the northwestern Atlantic over the same time period. To date 32 percent of open ocean sharks and rays are threatened with extinction.

These dire statistics pushed sharks to the center of the CITES meeting. However, out of eight species of shark considered, not one of them received enough votes to garner protection. The porbeagle shark actually won enough votes, but Asian countries were able to force a second vote just before the meeting closed that left the porbeagle, like its cousins, unprotected.

As top predators both sharks and Atlantic bluefin tuna play an important role in the ecosystem by controlling prey species populations and thereby also affecting their prey’s prey. Without sharks and tuna, the whole marine ecosystem—like Yellowstone was without wolves—will likely go topsy-turvy.

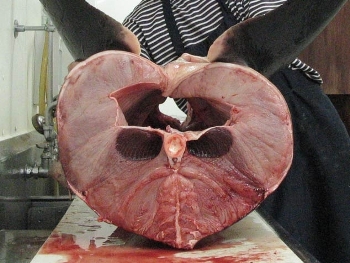

Porbeagle shark being prepared. Photo by: Matthieu Deute. |

Japan is the villain of this piece—the train tourist with gun resting on the window sill leisurely blasting away—since it repeatedly lobbied hard against any marine species receiving any protection or increased regulations.

China, Russia, and Canada were Japan’s willing accomplices. While Russia and China alliance with Japan may not be surprising, Canada’s is, especially considering both the US and the EU supported bans. But Canada has become an environmental pariah: one could argue, in fact, that Canada’s current government makes the Bush Administration look almost environmental. Joining up with Japan at CITES is only Canada’s most recent snub to global environmental sustainability.

The interesting thing about Japan’s behavior is that its government is fully aware that one day soon it will no longer be able to fish (or eat) Atlantic bluefin tuna. Either a ban will actually go through or, more likely, there simply will be no more fish to catch. Given the situation it would be a far wiser move for Japan’s economy to protect the fish now, so that in coming decades it can still consume the Atlantic bluefin tuna in small amounts, charging consumers a premium. However, instead of a sustainable environment producing a sustainable economy, Japan has chosen greed, and greed by definition knows no future, only the present. Waste is no different.

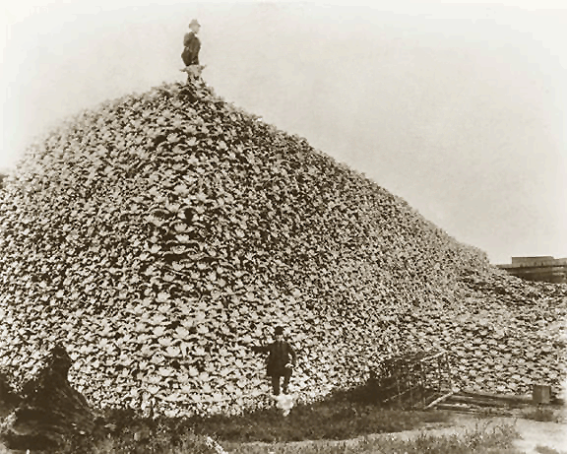

The near-demise of the American bison was also due to a combination of greed and waste: Americas slaughtered millions of bison both for their skins and in a truly cruel government program to starve out Native Americans. Prior to European arrival in North America, bison were likely long managed by Native Americans through hunting and burning prairies. Arrival of European disease decimated Native populations however, and in turn some researchers believe the bison population boomed and even expanded its range, that is, until European settlers made their way into the west.

Despite this long history, the story of the American bison actually ended happily…well somewhat. Thanks to the efforts of several conservationists, most notably James “Scotty” Philip, the American bison didn’t vanish entirely from the Earth—a possibility that may seem hard to imagine today, but a hundred years ago was quite likely.

American Bison. USDA photo by Jack Dykinga. |

Instead the American bison survives today to roam…America’s vanished prairie. One can find American bison in protected areas in small populations—nothing like what once roamed America’s west. Driving across America, however, one is most likely to see bison not in the wild, but behind fences as farm animals. These are not considered by the government ‘true’ bison, since genetics testing shows that many of the ‘farmed’ bison have interbred widely with cattle.

This, very well may be the same fate for bluefin tuna and sharks: remnants of the population being farmed for humanity’s ever-expanding appetite, perhaps crossbred with other tuna or shark species, or simply genetically modified to produce more meat—or in the case of sharks, bigger fins—per fish.

So, when it comes to human greed and waste, do not delude yourself: we will knowingly exploit a megafauna species—the Atlantic bluefin tuna, sharks, or the American bison—to extinction (or a fate nearly as bad) today, just as we did yesterday. We have not progressed, but refusing to learn from the past, like the ignorant, we are doomed to repeat it. Of course, unlike the ignorant, we repeat it with the full knowledge of our consequences, yet not even this stops us.

Where this cycle will end, I don’t know. But it’s very likely that one or two hundred years from now the oceans will look as different and lonely as today’s western America would appear to Lewis and Clark: little remaining but the absence of what was.

Photograph from the mid-1870s of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer.

Related articles

Critically Endangered bluefin tuna receives no reprieve from CITES

(03/18/2010) A proposal to totally ban the trade in the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna failed at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), surprising many who saw positive signs leading up to the meeting of a successful ban.

Extinction outpaces evolution

(03/09/2010) Extinctions are currently outpacing the capacity for new species to evolve, according to Simon Stuart, chair of the Species Survival Commission for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

UN to protect seven migratory sharks, but Australia opts out

(02/17/2010) One hundred and thirteen countries have signed on to an agreement to protect seven migratory sharks currently threatened with extinction byway of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), according to the UN Environment Program (UNEP). The agreement prohibits hunting, fishing, or deliberate killing of the great white shark, basking shark, whale shark, porbeagle shark, spiny dogfish, as well as the shortfin and longfin mako sharks. However, Australia has declared it will ignore certain protections.

Extinct animals are quickly forgotten: the baiji and shifting baselines

(02/23/2010) In 2006 a survey in China to locate the endangered Yangtze River dolphin, known as the baiji, found no evidence of its survival. Despondent, researchers declared that the baiji was likely extinct. Four years later and the large charismatic marine mammal is not only ‘likely extinct’, but in danger of being forgotten, according to a surprising new study ‘Rapidly Shifting Baselines in Yangtze Fishing Communities and Local Memory of Extinct Species’ in Conservation Biology. Lead author of the study, Dr. Samuel Turvey, was a member of the original expedition in 2006. He returned to the Yangtze in 2008 to interview locals about their knowledge of the baiji and other vanishing megafauna in the river, including the Chinese paddlefish, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish. In these interviews Turvey and his team found clear evidence of ‘shifting baselines’: where humans lose track of even large changes to their environment, such as the loss of a top predator like the baiji.

Actions taken to save sharks ‘disappointing’

(11/15/2009) Environmentalists say that the International Commissions for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) did not do enough in their yearly meeting to protect the ocean’s sharks.

Governments, public failing to save world’s species

(11/04/2009) According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) 2008 report, released yesterday, 36 percent of the total species evaluated by the organization are threatened with extinction. If one adds the species classified as Near Threatened, the percentage jumps to 44 percent—nearly half.

Atlantic bluefin tuna should be banned internationally: ICCAT scientists

(10/29/2009) Scientists with the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) have said in a new report that a global ban on Atlantic bluefin tuna fishing is justified. ICCAT meets in November to decide if they will follow their scientist’s recommendations.

Over 30 percent of open ocean sharks and rays face extinction

(06/25/2009) The first global study of open ocean (pelagic) sharks and rays found that 32 percent of the species are threatened with extinction largely due to overfishing and bycatch, making pelagic sharks and rays more threatened than birds (12 percent), mammals (20 percent), and even amphibians (31 percent), which are considered to be undergoing an extinction crisis. The situation worsens when only sharks taken in high-seas fisheries are considered: 52 percent of these species are threatened.

Will jellyfish take over the world?

(06/16/2009) It could be a plot of a (bad) science-fiction film: a man-made disaster creates spawns of millions upon millions of jellyfish which rapidly take over the ocean. Humans, starving for mahi-mahi and Chilean seabass, turn to jellyfish, which becomes the new tuna (after the tuna fishery has collapsed, of course). Fish sticks become jelly-sticks, and fish-and-chips becomes jelly-and-chips. The sci-fi film could end with the ominous image of a jellyfish evolving terrestrial limbs and pulling itself onto land—readying itself for a new conquest.

Marine scientist calls for abstaining from seafood to save oceans

(06/08/2009) In April marine scientist Jennifer Jacquet made the case on her blog Guilty Planet that people should abstain from eating seafood to help save life in the ocean. With fish populations collapsing worldwide and scientists sounding warnings that ocean ecosystems—as edible resources—have only decades left, it is perhaps surprising that Jacquet’s call to abstain from consuming seafood is a lone voice in the wilderness, but thus far few have called for seafood lovers to abstain.

Mediterranean bluefin tuna has only three years left unless fishery closes

(04/14/2009) If the Mediterranean bluefin tuna fishery is not closed, the bluefin will be functionally extinct by 2012 according to a new analysis from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). While the population has undergone steep declines for over a decade, fishery managers and policy-makers have continually ignored calls from scientists that fishing must stop if the Mediterranean bluefin tuna is to survive.