Could the carbon market save the Amazon rainforest?

Could the carbon market save the Amazon rainforest?

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

November 29, 2007

While deforestation and climate change threaten to accelerate the loss of Amazon rainforest, a bold initiative could fund conservation

The global carbon market could play a key role in saving the Amazon from economic development and the effects of climate change, which could otherwise trigger dramatic ecological changes, reports a new paper published in Science. The authors argue that a well-articulated plan, financed by carbon markets, could prevent the worst outcomes for the Amazon forest while generating economic benefits for the region’s inhabitants.

The paper, “Climate Change, Deforestation, and the Fate of the Amazon”, is written by Yadvinder Malhi of the Oxford University, J. Timmons Roberts of Oxford University and the College of William and Mary, Richard A. Betts of the Met Office Hadley Centre in the UK, Timothy J. Killeen of Conservation International, Wenhong Li of the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Carlos A. Nobre of the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE) in Brazil. Below is a summary of some of the key points of the “review” paper.

The Amazon

The Amazon contains Earth’s largest tropical forest: in 2001 it covered about 5.4 million square kilometers across nine South American countries (62 percent of which is in Brazil). Its extent is so great that the ecosystem fuels its own rainfall — 25 to 50 percent of precipitation is recycled through evapotranspiration by tree — and affects weather as far away as the Midwest of North America. Amazon forests also store tremendous amounts of carbon, house perhaps one quarter of the world’s terrestrial species, and account for 15 percent of global terrestrial photosynthesis

Deforestation

Deforestation in Brazil |

By 2001 roughly 837,000 square kilometers of the Amazon forest had been cleared. Since then, while deforestation rates in Brazil have fluctuated on an annual basis depending on commodity prices, currency swings, and law enforcement initiatives, the country has lost another 120,000 square kilometers of forest. Most clearing is concentrated in the so-called “arc of deforestation” on the southern and eastern margins of the Basin, and is driven primarily by expansion of cattle and soybean production. Clearing in wetter, more remote areas like the northwestern Amazon is minimal. Nevertheless, deforestation figures significantly understate disturbance in the region, where vast areas are affected by selective logging and low-intensity fires that make forests more vulnerable to future burning. Fragmentation is also taking a toll, reducing the quality of habitat for primary forest-dwelling wildlife, causing changes in forest trigger, and bolstering risk of fire.

Climate change

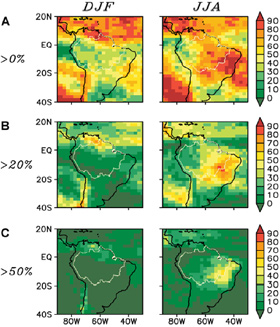

|

In recent decades the rate of warming in Amazonia has been about 0.25°C decade but future forecasts carry large uncertainties due to questions over how the Amazon forest itself will respond to higher atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide and whether the ecosystem will be a net sink or source of greenhouse gas emissions. Under mid-range emission scenarios, temperatures are projected to rise 3.3°C (range 1.8-5.1°C) this century, though substantially larger increases of up to 8°C could occur should large-scale forest dieback trigger regional “biophysical” shifts. The impact of climate change on precipitation is also poorly understood, though the authors say that models from the IPCC–which show “no consistent trend in annual, Amazon-wide rainfall over the 21st century”–are probably too conservative by underestimating rainfall and failing to incorporate

“When the effects of rising temperatures on evapotranspiration are included, almost all models indicate increasing seasonal water deficit in eastern Amazonia,” the authors write. “This drying becomes more severe with greater magnitudes of global warming, and is exacerbated by ecosystem feedbacks such as forest die-back and reduced transpiration in remaining forests.”

The authors note that some models suggest the Amazon forest-climate system may have two stable states and the loss of 30 to 40 percent of forest cover could trigger a shift for much of the Amazon to a drier state.

“Loss of forest also results in (i) decreased cloudiness and increased inolation, (ii) increased land surface reflectance, approximately offsetting the cloud effect, (iii) changes in the aerosol loading of the atmosphere from a hyperclean “green ocean” atmosphere to a smoky and dusty continental atmosphere that can modify rainfall patterns, and (iv) changes in surface roughness and hence wind speeds and the large-scale convergence of atmospheric moisture that generates precipitation,” Malhi and colleagues write.

Synergistic effects of climate change and deforestation

The authors say that while artificial drought experiments and remote sensing show that intact Amazonian forests are more resilient to climatic drying than is typically supposed, the combined effects of deforestation with climate change could increase its vulnerability to fire and large-scale die-off.

“The synergistic combination of global warming, deforestation and increased forest fires represents a real threat to the functioning of Amazonian ecosystems and could lead to a large reduction of forest cover in the Amazon in this century,” co-author Dr. Carlos Nobre told mongabay.com.

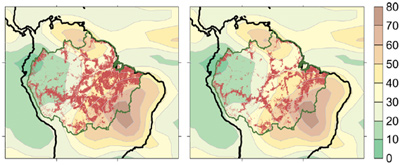

|

“The speed and magnitude of current human pressures on forests are affecting forest resilience. Forests close to edges are vulnerable to elevated desiccation, tree mortality, and fire impacts,” the authors state. “Rainforests may become seasonally flammable in dry years, but without anthropogenic ignition sources fire is a rare occurrence. Hence fire has been a weak evolutionary selective force, and as a result many tree species lack adaptations that allow them to survive even low-intensity fires.”

“Logging and forest fragmentation also increase the flammability of forests by providing substantial combustion material, opening up the canopy and drying the understory and litter layer, and greatly increasing the amount of dry fire-prone forest edge,” they add, while noting that 28 percent of the Brazilian Amazon faces “incipient” fire pressure.

Further threat comes from ambitious plans to develop the Amazon for agriculture, energy, timber, and minerals. Manifested as the multibillion-dollar “Avança Brasil” program in Brazil and other names elsewhere, the authors say current plans for infrastructure expansion could reduce the Amazon forest from 5.4 million square miles in 2001 to 3.2 million square kilometers by 2050. Absent of other deforestation and impacts of climate change, this development alone would release some 32 petagram (32 billion metric tons) of carbon, or more than four years’ worth of global carbon emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

While the authors expect most clearing to occur in the south and east, they say the remote northwestern Amazon–which holds the bulk of the region’s biodiversity–is “vulnerable to hydrocarbon exploration and oil-palm plantations that are suitable for wet climates and acidic soils and have already replaced many of Asia’s tropical rainforests.”

“Drying of Amazonia, whether caused by local or global drivers, could greatly expand the area suitable for soy, cattle and sugarcane, accelerating forest disappearance,” the authors write.

Preparing for climate change in the Amazon

While the outlook under some scenarios is dire, the authors say that planning for development and climate change could mitigate some of the worst potential outcomes in the Amazon. The authors suggest five key recommendations: limiting the extent of deforestation well below possible climatic thresholds (30-40 percent deforested) through the use of a matrix of large protected areas and human-managed landscapes; controlling fire through education and law enforcement; maintaining broad species corridors for migration; protecting river corridors; conserving the core northwestern Amazon for its high biodiversity. By implementing these measures, the authors estimate that expected deforestation could be reduced from a loss of 47 percent of the original forest area by 2050 to a 28 percent loss, avoiding 17 petagrams of carbon emissions.

Financing a Climate-Resilience Plan for Amazonia

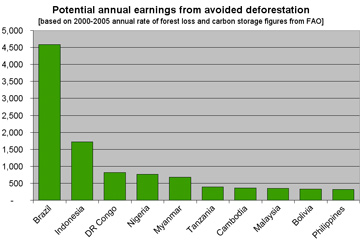

Potential earnings from avoided deforestation, based on annual rate of forest loss in selected countries from 2000 to 2005 and average carbon storage values from FAO. Carbon is assumed to be priced at $5 per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. Note: these figures only include emissions from deforestation, not land degradation. By some estimates, Indonesia’s annual emissions may be higher than those of Brazil due to degradation of carbon-rich peatlands. Calculations are by mongabay and are not in any way related to the Science paper. |

The authors say that financing a climate-resilience plan for the Amazon will be a challenge due to “the drive of globalizing market forces, insufficient financial resources, provision of open access to information, limited technical and governance capacity, and ineffective enforcement of rule of law,” but hope that new proposals for mitigating climate change could act as a “countervailing force to the economic pressures for

deforestation.”

Specifically, the authors say that REDD (reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries), the concept in which tropical forest countries are compensated by industrialized countries for ecosystem services provided by forests, could be key to providing funds to preserve critical parts of Amazonia. REDD will be a topic of discussion at next week’s U.N. climate meeting in Bali.

“[REDD has] the potential to shift the balance of underlying economic market forces that currently favor deforestation (45), by raising billions of dollars for the ecosystem services provided by rainforest regions, but will require exceptional planning, execution and long-term follow-through,” the authors write.

“Avoided emissions from reducing deforestation of the Amazon tropical forests can be the key contributions by Amazonian countries to global efforts to mitigate climate change in the coming decades,” added co-author Carlos Nobre in an email exchange with mongabay.com. “For that to become feasible, it is urgently needed that the UNFCCC implement a new mechanism to compensate tropical countries which in fact reduce deforestation rates”.

CITATION: Malhi, Y. et al (2007). “Climate Change, Deforestation, and the Fate of the Amazon,” www.sciencexpress.org / 29 November 2007 / Page 4/ 10.1126/science.1146961

Related articles

Dutch bank arranges carbon-conservation deal in the Amazon rainforest

(11/27/2007) Dutch bank Rabobank will launch the first-ever carbon credits project in the Xingu region of the Brazilian Amazon, reports The Financial Times.

Ground-breaking Amazon rainforest imagery will help monitor deforestation

(11/27/2007) Scientists have developed a ground-breaking high resolution snapshot of 400,000 square kilometers of Amazon rainforest. The work will help researchers remotely monitor deforestation, according to the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC).

|

Subtle threats could ruin the Amazon rainforest

(11/7/2007) While the mention of Amazon destruction usually conjures up images of vast stretches of felled and burned rainforest trees, cattle ranches, and vast soybean farms, some of the biggest threats to the Amazon rainforest are barely perceptible from above. Selective logging — which opens up the forest canopy and allows winds and sunlight to dry leaf litter on the forest floor — and 6-inch high “surface” fires are turning parts of the Amazon into a tinderbox, putting the world’s largest rainforest at risk of ever-more severe forest fires. At the same time, market-driven hunting is impoverishing some areas of seed dispersers and predators, making it more difficult for forests to recover. Climate change — an its forecast impacts on the Amazon basin — further looms large over the horizon.

|

2007 Amazon fires among worst ever

(10/22/2007) By some measures, forest fires in the Amazon are at near-record levels, according to analysis Brazilian satellite data by mongabay.com. A surge in soy and cattle prices may be contributing to an increase in deforestation since last year. Last year environmentalists and the Brazilian government heralded a sharp fall in deforestation rates, the third consecutive annual decline after a peak in 2004. Forest loss in the 2006-2007 season was the lowest since record-keeping began in the late in 1970s. While the government tried to claim credit for the drop, analysts at the time said that commodity prices were a more likely driver of slow down: both cattle and soy prices had declined significantly over the previous months.

Brazil to search for oil in the Amazon

(10/21/2007) Brazil’s plan to seek oil in the Western Amazon has upset environmentalists, reports the Associated Press (AP). The National Petroleum Agency, or ANP, plans to put US$36 million toward oil and gas exploration in Acre, a state bordering Bolivia, according to Brazilian state media Agencia Brasil, but environmental officials say no impact study has been done to assess how the plan could affect the Amazon.

Is the Amazon more valuable for carbon offsets than cattle or soy?

(10/17/2007) After a steep drop in deforestation rates since 2004, widespread fires in the Brazilian Amazon (September and October 2007) suggest that forest clearing may increase this year. All told, since 2000 Brazil has lost more than 60,000 square miles (150,000 square kilometers) of rainforest — an area larger than the state of Georgia or the country of Bangladesh. Most of this destruction has been driven by clearing for cattle pasture and agriculture, often in association with infrastructure development and improvements. Higher commodity prices, especially for beef and soy, have further spurred forest conversion in the region. While drivers of Amazon deforestation are stronger than ever, mounting concerns over climate change and the effort to reign in greenhouse gas emissions may provide new economic incentives for landowners to preserve forest lands through a concept known as “avoided deforestation”.

Biofuels driving destruction of Brazilian cerrado

(8/21/2007) The cerrado, wooded grassland in Brazil that once covered an area half the size of Europe, is fast being transformed into croplands to meet rising demand for soybeans, sugarcane, and cattle. The cerrado is now disappearing more than twice as the rate as the neighboring Amazon rainforest, according to a Brazilian expert on the savanna ecosystem.

Amazon deforestation in Brazil falls 29% for 2007

(8/13/2007) Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell 29 percent for the 2006-2007 year, compared with the prior period. The loss of 3,863 square miles (10,010 square kilometers) of rainforest was the lowest since the Brazilian government started tracking deforestation on a yearly basis in 1988.

|

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(6/6/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

|

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(6/3/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.

|

U.S. ethanol may drive Amazon deforestation

(5/17/2007) Ethanol production in the United States may be contributing to deforestation in the Brazilian rainforest said a leading expert on the Amazon. Dr. Daniel Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center said the growing demand for corn ethanol means that more corn and less soy is being planted in the United States. Brazil, the world’s largest producer of soybeans, is more than making up for shortfall, by clearing new land for soy cultivation. While only a fraction of this cultivation currently occurs in the Amazon rainforest, production in neighboring areas like the cerrado grassland helps drive deforestation by displacing small farmers and cattle producers, who then clear rainforest land for subsistence agriculture and pasture.

|

Amazon rainforest locks up 11 years of CO2 emissions

(5/8/2007) The amount and distribution of above ground biomass (or the amount of carbon contained in vegetation) in the Amazon basin is largely unknown, making it difficult to estimate how much carbon dioxide is produced through deforestation and how much is sequestered through forest regrowth. To address this uncertainty, a team of scientists from Caltech, the Woods Hole Institute, and INPE (Brazil’s space agency), have developed a new method to determine forest biomass using remote sensing and field plot measurements. The researchers say the work will help them better understand the role of Amazon rainforest in global climate change.

|

Global warming could cause catastrophic die-off of Amazon rainforest by 2080

(10/22/2006) For the Amazon, there is an immense threat looming on the horizon: climate change could well cause most of the Amazon rainforest to disappear by the end of the century. Dr. Philip Fearnside, a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil and one of the most cited scientists on the subject of climate change, understands the threat well. Having spent more than 30 years in Brazil and now recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest, Fearnside is working to do nothing less than to save this remarkable ecosystem. Fearnside believes saving the Amazon will require a fundamental shift in perception where the Amazon is recognized as an asset beyond the current price of mahogany, soybeans, or cattle, where its value is only unlocked by its destruction. The Amazon is far worth more than this he says. It can play a key role in fighting climate change while providing economic sustenance for millions through sustainable agriculture and rational utilization of its renewable products. It can serve as a storehouse for biodiversity while at the same time ensuring reliable water supplies and moderating regional temperature and precipitation. In short, maintaining the Amazon as a viable ecosystem makes sense economically and ecologically — it is in our best interest to preserve this resource while we still can.

|

Rainforests face myriad of threats says leading Amazon scholar

(10/16/2006) The world’s tropical rainforests are in trouble. Spurred by a global commodity boom and continuing poverty in some of the world’s poorest regions, deforestation rates have increased since the close of the 1990s. The usual threats to forests — agricultural conversion, wildlife poaching, uncontrolled logging, and road construction — could soon be rivaled, and even exceeded, by climate change and rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Understanding these threats is key to preserving forests and their ecological services for current and future generations. William F. Laurance, a distinguished scholar and president of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) — the world’s largest scientific organization dedicated to the study and conservation of tropical ecosystems, is at the forefront of this effort.