This post is an expanded version of an article that appeared in August on Yale e360: Easing The Collateral Damage Fisheries Inflict on Seabirds.

Salvin’s albatross (Thalassarche salvini) is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Carl Safina.

A life on the ocean is a perilous one for any bird. They must expend energy staying aloft for thousands of miles and learn to be marathon swimmers; they must seek food beneath treacherous waves and brave the world’s most extreme climates; they must navigate the perils both of an unforgiving sea and far-flung islands. Yet seabirds, which includes 346 global species that depend on marine ecosystems, have evolved numerous strategies and complex life histories to deal with the challenges of the sea successfully, and they have been doing so since the dinosaur’s last stand. Today, despite such a track record, no other bird family is more threatened; yet it’s not the wild, unpredictable sea that endangers them, but pervasive human impacts.

“They are exquisitely beautiful, they are extreme athletes, and their travels and migratory skills inspire awe,” Carl Safina, author of Eye of the Albatross: Visions of Hope and Survival and founding president of the Blue Ocean Institute, says of seabirds. Starting his career by researching seabirds, Safina says many of these beautiful athletes “are in trouble.”

In fact, a recent paper in Bird Conservation International found that the 28 percent of the world’s seabirds are listed as threatened by the IUCN Red List—over double the percentage of birds imperiled as a whole, 12 percent. Perhaps even more worrying, nearly half (46 percent) of sea birds are currently in decline.

“Overall, seabirds are more threatened than other comparable groups of birds and their statuses have deteriorated faster over recent decades,” the researchers write, raising an alarm that not enough is being done to mitigate the many and rising threats to seabirds.

Still conservationists are not standing by. Seabird nesting islands are being cleared of invasive species that have decimated some populations. Innovative regulations and enforcement programs are helping to mitigate some industrial fisheries from killing seabirds as bycatch. Meanwhile, new research is shining a light on just how many fish in the sea may be needed to support healthy populations.

From albatross to penguins

King penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus), one of the few penguins listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Carl Safina.

Comprising a huge variety of wonderfully-named birds—petrels, shearwaters, sea ducks, loons, prions, fulmars, grebes, tropicbirds, frigatebirds, pelicans, gannets, boobies, cormorants, shags, phalaropes, gulls, terns, kittiwakes, prions, noddys, auks, jaegers, guillemots, murrelets, puffins, penguin, and of course the albatross—the most endangered of the seabirds are generally those most inseparable from the open ocean, such as albatross, petrels, and penguins.

If there were a king of seabirds, it would be the albatross. Comprising 22 species, albatross are the ocean’s Odysseus, logging thousands of miles over the seas in just a few weeks, without the benefit of landmarks. The only time albatross stop soaring is to breed—again not unlike Odysseus. In fact, they may even sleep on the wing. They mate for life and meet up once a year to produce a single precarious offspring. Albatross live at least a half century and maybe even longer.

The largest of the albatross family are the so-called “great albatross” in the genus Diomedea; in fact the aptly-named wandering albatross has the largest wingspan of any bird in the world, even larger than much heavier fliers such as the Andean condor, the great bustard, or the Dalmatian pelican. Reaching three and a half meters (eleven and a half feet) the wandering albatross is more hang glider than bird.

If the five species in the Near Threatened category are included, every single one of the world’s 22 albatross species are considered threatened. Three of the species are at the gravest risk—the waved albatross (Phoebastria irrorata), the Amsterdam albatross (Diomedea amsterdamensis), and the Tristan albatross (Diomedea dabbenena)—each listed as Critically Endangered.

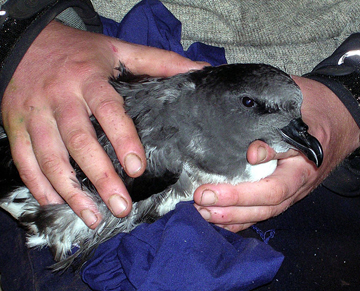

Magenta petrel (Pterodroma magentae) chick held by a conservationist. Around 150 of this species remain. |

The petrels—which includes shearwater, storm-petrels, prions, and fulmars—are closely related to the albatross and nearly as threatened. All but two of the hundred-plus petrels are smaller than albatross, but like the albatross, petrels nest on far-flung islands and utilize the vast seas as feeding grounds. The species are named after Saint Peter (‘petrel’ is Latin for Peter) due to their skill of hovering over the sea’s surface as they feed, looking as if they are almost walking on water. With a fossil record going back 60 million years, petrels are some of the world’s oldest birds and for a time may have even shared the skies with pterosaurs. Currently, nearly half (48 percent) of the petrels are imperiled if the Near Threatened category is included.

The smallest and least-known of all the seabirds are the storm petrels. Comprising 26 species, these sparrow-sized birds float over the sea’s surface scooping up fish and plankton. Four of the world’s storm-petrels are listed as Data Deficient—the only seabirds to be listed as such—meaning scientists simply lack the basic information needed to assess their status. Meanwhile, one species, the Guadalupe storm petrel (Oceanodroma macrodactyla), is likely extinct.

Arguably the most recognizable birds worldwide, and probably the most beloved by the general public, are the penguins. Still, few people realize just how imperiled penguins are: over 60 percent of the world’s 18 penguins are threatened with extinction. If the Near Threatened category is added, the percentage jumps to over eighty. The only penguins that remain relatively secure are those that breed in Antarctica, but even these have seen worrisome declines in recent years and scientists say climate change could make things worse.

Extinction is not an unrealistic fate for many of the world’s seabirds. Already the large Saint Helena petrel (Pterodroma rupinarum), the small Saint Helena petrel (Bulweria bifax), and the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) have likely vanished for good in modern times.

Meanwhile, the Magenta petrel (Pterodroma magentae) is thought to be down to just 150 individuals, the Amsterdam albatross just over a hundred, and the New Zealand storm-petrel (Oceanites maorianus) only has around fifty survivors.

On land

A black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) colony on the Falkland Islands. The black browed albatross is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Carl Safina.

Many of the world’s seabirds, especially those that depend on island-breeding, are most vulnerable when attempting to ensure the future of their species. This wasn’t always the case. Far-off islands have long been safe bets for seabirds, which is why they colonized them in the first place. Almost all of them were free of terrestrial predators, while humans didn’t land on many of these islands until recent centuries.

But the advantages that kept the islands havens for hatching and rearing chicks for millions of years, has now turned them into massacre zones.

“Many [seabirds] nest on islands that had no four-footed mammals (or two legged ones) until the last blink of evolutionary time,” explains Safina. “Rats, cats, people; they’ve caused the loss of many millions of birds from former strongholds. They still do.”

The South Georgia shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps georgianus) is found only on the island. Photo by: Liam Quinn. |

When humans began landing on these rocky islands, they often left-behind seafaring companions: rats, mice, cats, dogs, goats, fox, pig, rabbit, and even cattle. These animals either directly preyed on unwitting nesting birds or quickly decimated the ecology of the breeding site, leading to substantial declines in many seabirds and even extinction in some. In fact, the long security from predation allowed seabirds to evolve into slow-breeders.

“Many seabirds don’t breed until they’re three years old; some albatrosses, not until they’re ten,” Safina explains. Such slow breeding makes populations liable to sudden collapse when confronted by a new threat, and slow to rebuild even when the threat is mitigated.

“Of the top 10 threats to threatened seabirds, invasive species (invariably acting at the breeding site) potentially affect 73 species (75 percent of all threatened seabird species and nearly twice as many as any other single threat),” the researchers note.

Eradication of invasive species on many islands has occurred in the past few decades, giving hope for the recovery of some seabird populations. According to the researchers, 284 islands have had rodents successfully eradicated. Still, many hugely important seabird sites remain infested including at least 75 notable islands where eradication efforts are still required.

“There have been some inspiring successes with seabird populations responding to successful removal of invasive alien species such as cats, rats, pigs and goats, but there are still dozens of islands and breeding colonies where removing such introduced species is an urgent priority,” lead author Stuart Butchart co-author of the paper and global species officer with the conservation group, BirdLife International says.

Safina adds that South Georgia remains the highest priority for eradication. A wide diversity of seabirds nest on South Georgia, which is located deep in the Southern Ocean and the largest landmass going south before one lands on Antarctica. The UK territory is now the world’s biggest protected area, though protection does not extend to the seas surrounding it. A rodent eradication program began last year on the island—the most ambitious to date—while scientists also plan to cull reindeer herds that were brought there in the early 1900s.

Research last year found records of nearly 1,500 species on and around South Georgia, making the bitter-cold island and its surrounding waters more biodiverse than the Galapagos.

Even as experts work to rid such islands of invasive pests, another threat is rising for nesting sites: climate change. Sea levels have been going up about 3 to 3.5 millimeters annually since the early 1990s. While that may not sound much, the sea could easily reach levels whereby many low-lying islands could see regular flooding and eventually complete submersion, putting a massive number of seabird nesting areas in peril. In fact, the paper found that 39 seabirds (40 percent) could be susceptible to rising seas, although it stated this was a problem for the “medium to long term.”

In the water

Southern giant petrels (Macronectes giganteus) off New Zealand. This species is listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Carl Safina.

Keeping seabirds safe while nesting on islands proves relatively straight-forward in the near future: simply rid the islands of invasive species and keep them from returning. But keeping birds safe in the water is a different—and more complicated—story altogether.

The list of human-induced dangers facing birds in seawater is long: plastic and other pollution, drowning on long lines or in gillnets, hunting or trapping, fossil fuel exploitation and mining, and a decline in food due to overfishing.

“It is important to note that some threats, especially bycatch, coastal pollution and overfishing, are assessed to have higher impact on a larger proportion of the species they affect, considerably increasing their overall importance,” reads the paper.

Bycatch is arguably the most immediate for bolstering populations and preventing extinction. According to the study, 40 of the world’s threatened seabird species, nearly half, are drowned as bycatch, including those most tightly connected to the open ocean: albatross and petrels.

Seabirds are attracted to bait used by industrial fisheries, but it’s an attraction that can kill. In longline fisheries, which began to boom in the 1980s, fishermen spool out fishing lines stretching up to 80 miles (130 kilometers) and baited with thousands of hooks. Used to maximize catches, longlines have also greatly increased bycatch, or the killing of non-target species. Easily entangled on the line or caught by a hook, seabirds drown en masse.

“There is no single prescription for reducing bird mortality in fishing gear and means to mitigate seabird bycatch are highly species and fishery specific,” says Ramunas Zydelis with the Center for Marine Conservation at Duke University, adding that, “in general, mitigation measures aim to make fishing vessels less attractive to birds.”

How do you make tasty bait less attractive? Common methods include using weighted lines that sink below the surface or attaching streamers to lines—known as tori lines—to scare off birds. Shifting how and when fisheries work also is important, such as setting lines in low light when birds are less active or no longer throwing offal, or chum, when setting lines.

Seabirds trailing a longline vessel. Seabirds are attracted by the bait used to catch fish, but it’s a lethal attraction. Photo by: NOAA. |

Pamela Toschik with NOAA say marine researchers refer to these methods as the “shrink and defend” model.

“A very effective way to prevent bycatch of seabirds is to shrink the area in which the hooks are available (e.g., by weighting the lines so the baited hooks sink faster) and then defend the remaining area (e.g., with bird scaring lines),” Toschik says, noting that multiples methods used simultaneously are the best way to keep birds from being hooked or entangled.

“In regions where environmental organizations, fishery managers and fishermen work together—great results have been achieved,” Zydelis adds. “For instance, seabird bycatch has been reduced by 90 percent and more in longline fisheries in the Southern Ocean, Hawaii, Alaska, South Africa and New Zealand.”

Such practices are catching on. Since 2004, four of the five major tuna fisheries, long notorious for bycatch, have implemented bycatch mitigation methods.

Toschik adds that the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) has cut bycatch of seabirds in the Southern Ocean from “thousands per year to near zero in the legal fishery.”

Apart of the key has been that all CCAMLR fishing vessels have scientific observers aboard. Scientific observers’ are key to collecting data on lone boats that ply the sea thousands of miles from land. The “observer,” who is employed independent of the fishery, monitors bycatch, not only of seabirds, but also marine turtles, cetaceans, and non-target fish.

An anonymous observer, who did seven tours on longline fisheries in the Pacific off Hawaii, says that ships there used several methods to mitigate bycatch, including “dying the bait a specific hue of blue to camouflage it, thawing the bait or weighting it to ensure it doesn’t float, using a special device which sets the line away from the boat so its wake doesn’t bring the baited hook to the surface, among others.”

While the longline fisheries near Hawaii are particularly concerned about marine turtle bycatch, they also have to keep an eye out for seabirds.

“The major avian species of concern is the short-tailed albatross, but relatively few have been observed in the region. In my experience, the black-footed albatross was the species suffering the highest bycatch rates, and from what I know there were no quotas in place to protect them,” the observer says. The IUCN Red List categorizes the black-footed albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) as Vulnerable.

During their seven tours, the observer pulled up three drowned black-footed albatross.

Black footed-albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) is listed as Vulnerable. Photo by: James Lloyd. |

“It was very difficult,” the observer admits. “At first, I thought I hadn’t been monitoring closely enough the mitigation procedures, but I realized that even if everything is done as it should be, bad things can still happen. These vessels set upwards of 2,000 hooks per day, each having the capability to catch a fish—or a bird, turtle, or whale. Mitigation procedures have had a huge impact on reducing bycatch rates, but it’s impossible to control for all conditions.”

In fact, estimates of the number of seabirds still killed by longlines—160,000-320,000 annually—remain hugely unsustainable.

For seven years, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has hosted an annual International Smart Gear Competition, which gives prize money for the best new ideas for mitigating bycatch. One of the most promising ideas has been the Underwater Baited Hook, which won the contest in 2009.

“A mechanical device sets the baited hooks at a preset depth in the vessels wake. This minimizes the chances of seabirds detecting the baited hooks and diving on them,” explains Mike Osmond, Senior Program Officer at WWF’s Fisheries Program. While this idea is still being field tested, others are already in use. The Yamazaki Double-Weighted Branchline, which won the contest just last year, is already a requirement in several tuna fisheries.

“The weighted branchline not only sinks the hooks within the confines of streamer lines, helping to prevent attacks by seabirds, but its unique design also reduces the chance of recoil and subsequent injury to the crew,” says Osmond. Notably, the new technology was developed by a Japanese fishing boat captain.

At least progress is being made on longline fisheries. Gillnets are another, though largely unstudied and unmitigated, killer. Experts believe that hundreds of thousands of diving seabirds—such as loons, grebes, seaducks, auks, cormorants, and shags—drown in gillnets every year. Gillnets, so-called because they catch fish by their gills, entrap diving birds when they are attracted to the fish catch. Despite their impact, Zydelis with the Center for Marine Conservation at Duke University, says knowledge of gillnet bycatch remains “patchy.”

“This is due to the fact that most of gillnet fisheries are operated by thousands of small scale artisanal fishermen. And these fisheries are often poorly monitored,” he notes, “therefore, monitoring of seabird bycatch in gillnet fisheries is the first step.”

Once researchers understand the threat, mitigation methods can be developed, as they were not long ago for longline fisheries. Already, some fishermen have used more visible nets and changed locations to lessen the impact of gillnets on birds.

Stopping bycatch isn’t just a problem for marine scientists and conservationists, says Stephen Kress, the Audubon Society’s Vice President for Bird Conservation, but “an issue for all.”

He notes, “While regulations may ultimately be necessary, fisheries should learn that adoption of minor changes in methods can save seabirds, while at the same time create more efficient operations that helps their ‘bottom line.’ There is great value in educating fishers about this win-win opportunity.”

A crested auklet (Aethia cristatella) covered in oil from a spill by a cargo vessel in Alaska. The crested auklet is listed as Least Concern. Photo by: US Fish and Wildlife Service. |

Seabird bycatch can slow down fishing operations and even close them altogether if there is a limited take of endangered species.

Despite the numerous ways to mitigate bycatch, many fisheries still do nothing to lessen bycatch, including those fisheries considered illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU), which may constitute 30 percent of some total fisheries. Not only are IUU fisheries further plundering the sea of fish, but they also taking bycatch, which given their nature, goes entirely undocumented.

“I highly doubt whether there is an efficient way to tackle bycatch in industrial IUU fisheries, except for trying to eliminate such fisheries altogether,” Zydelis notes. However he adds that fisheries and consumers could have a role in reducing bycatch even where governance is failing.

“To my opinion not all fishermen and fishery management organizations are sufficiently aware about detrimental effects of bycatch, nor are consumers,” he says. “Bycatch (or bycatch exceeding certain thresholds) should be illegal, regulations should be enforced, and finally there should be a pressure from consumers to receive bycatch-free seafood.”

While there has been an increase in products like “dolphin safe tuna” (which only concern dolphins and not other bycatch like seabirds), scientists say consumers could push fisheries further.

While bycatch is the most immediate and widespread killer of seabirds in the water, pollution also harms species in a wide-variety of ways. Plastic trash is often ingested by seabirds who mistake it for food; most deadly to chicks, ever-growing plastic debris can be lethal to adults as well. Pesticide runoff can also be harmful to populations in the long-term. Nitrogen runoff leads to massive algae blooms that, in some cases, strip seabirds of their protective oils leading to hypothermia and death. Finally, oil spills can decimate entire populations. Everyone remembers the monstrous photos of oil-doused pelicans and seabirds during the BP disaster, but oil spills—large and small—occur with monotonous regularity worldwide. The Exxon Valdez disaster in 1989 is believed to have killed up to 250,000 seabirds, and is still impacting the Prince William Sound ecosystem today. Heroic efforts saved tens-of-thousands of oiled African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) after a ship sunk off the coast of South Africa in 2000, but many of the penguins have suffered breeding problems since. Last year, an oil spill in New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty is believed to have killed around 20,000 seabirds while a spill in the remote Trista da Chunha islands hurt already endangered northern rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes moseleyi).

As gas and oil companies push even further and deeper into the oceans for more difficult energy deposits—such as those in the Arctic—its likely such spills will continue to be a major problem for seabirds and multitudes of other marine animals in the near future.

While bycatch and pollution are decimating some populations of seabirds, a third threat may be undercutting the entire food chain that these, and other marine species, depend on: overfishing.

A third for the birds!

A wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans) near Tasmania. The wandering albatross is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: J.J. Harrison.

Overfishing has become one of the most intractable and widespread problems in marine ecosystems. The plundering of the oceans for human consumption has pushed some fish, like bluefin tuna, towards extinction and threatened the abundance of non-target animals great and small. Still, overfishing has not always been high on the list of threats to seabirds due to a lack of research connecting seabird decline to overfishing, but this is changing. Recently, a ground-breaking study in Science found that not only are seabird populations intrinsically connected to prey abundance, but also at what level overfishing begins to hurt these sky and sea athletes.

Looking at 14 seabird species in seven marine ecosystems, scientists discovered that every time prey populations dropped below one third of the maximum abundance, seabird breeding suffered. In other words—no matter what ecosystem or species, —all seabirds stopped reproducing when prey levels declined below a set threshold, and they declined quickly and precipitously. For the first time, the research provided scientists a benchmark on how seabird populations react to prey decline.

“All the data sets showed a remarkably similar pattern,” co-author Ian Boyd at the Scottish Oceans Institute at the University of St. Andrews says. “I was initially skeptical that this [research] would show any consistency but I recall that when the data were all plotted out initially and showed such a consistent pattern I knew we were on to something.”

Interestingly, the research—which incorporated everything from penguins to gannets as well different preys species: sardines, anchovies, herring and prawns—found that a higher prey abundance than one-third above the maximum did not result in much greater seabirds populations, since total populations were limited by nesting space.

A pair of black-legged kittiwakes nesting on the cliffs of the Norwegian island Runde. Photo by: Islandmen. |

Boyd points to penguins in the Scotia Sea, Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) in the Loffoten Islands, and black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) in the Shetland Archipelago as prime examples of populations that have suffered due to prey decline. In the case of the kittiwakes, their abundant population plunged by 50 percent from 1990 to 2002 after their main prey species, sand eels, began to disappear. Although researchers believe the sand eel population did not suffer from local industrial fishing, concern for the kittiwakes and other seabirds spurred action to close down the fishery.

“In a very broad sense, the one-third rule was applied in this context,” Boyd says.

Connecting a single fishery to seabird decline however remains difficult.

“The story is complicated by the difference between population level and breeding success, which is what we used,” Boyd says, noting that it takes several years for a decline in prey to result in an actual population drop in seabirds, making causation tricky to prove.

“The most likely example of industry competition [with seabirds] is in the Peruvian anchovy fishery where there appear to have been long, sustained declines of seabirds as the fishery has grown,” Boyd adds.

David Ainley, a penguin expert, says that the anchovy fisheries, both in Peru a well as off the southwest coast of Africa, have put penguins at risk.

“This is especially true of the African penguin and the Humboldt penguin in the Benguela and Peru Currents, respectively, where the fisheries for anchovies are immense and have led to the severe depression in almost all seabird species breeding along those coasts,” Ainley says, noting that Humboldt penguins are also a victim of drowning in gillnets.

Boyd, however, cautions that even in the anchovy fisheries “the data are poor and the cause-effect relationship is circumstantial.”

More research will be needed to establish direct links between industrial fishing and seabird population drops, but for the first time scientists may have an understanding of just how seabird populations react to prey declines.

“When you think about it, its obvious that there should be some level of consistency. In fact, they all start to decline when food declines below the long-term average, which happens to be about the same as one-third of the maximum biomass,” Boyd explains. “What this is saying is that [seabirds] have evolved to exploit average to above-average feeding conditions. This isn’t really very surprising, but some things don’t become obvious until the evidence is right in front of you.”

A Chilean purse seiner scoops up several hundred tons of jack mackerel. Overfishing is one of the major threats to the world’s oceans according to scientists. Photo by: NOAA. |

Boyd and the study’s other co-authors argue that their findings should propel a new way of thinking about fishery management, with a rallying cry of “one third for the birds” not just to preserve seabird abundance but other species as well.

“Some may believe that this only applies to seabirds, but it is possible that the relationship also applies to many components of the ecosystem,” explains Boyd. “If this was used as a general rule in fisheries it is more likely to lead to sustainable fishing than current systems of management.”

However, not everyone believes that the slogan “one third for the birds” truly offers the solution.

Carl Safina, for his part, thinks the study points to a slightly different conclusion: seabirds quite simply require an abundance of prey that doesn’t dip below “average.” In other words, in good years, fisheries could catch surplus prey fish, but leave the rest for the birds and other wildlife.

“One-third doesn’t cut it,” Safina notes, adding that “even then, who knows whether seabird populations need periods of above-average prey abundance to allow populations to grow, to buffer poorer times when birds have to cope with below-average food density and lowered survival rates?”

But what is average? This question quickly become historical in nature, i.e. what average are we referring to? In fact, trying to decide on an average abundance may be more difficult than we realize.

A recent theory, developed by fisheries expert Daniel Pauly, posits that human societies forget—from one generation to the next or even in individual lifetimes—what natural abundance used to looks like as ecosystems become increasingly degraded. In other words, today’s abundance would pale in comparison to that seen even a generation ago. The theory, known as “shifting baselines,” means that perhaps “healthy” seabird populations today could in fact be quite gaunt.

David Ainley says that these “shifting baselines” may unwittingly lead researchers into being too optimistic.

“It’s easier to feel good or think that there is still hope with more intelligent management if one defines the current conditions as the baseline [instead of looking at historical data],” he says.

Safina also says he’d like to see a deep historical approach in upcoming research, simply to dispel some of the questions that remain.

“A historical analysis might show that in the past, prey fish numbers were much higher, and seabird numbers were much higher because they had much more food. Or maybe not; we’d need that historical analysis to really understand how much food seabirds ‘need,’ and we’d need to decide how large seabird populations ‘should be’ to be ‘large enough.'”

In other words, Safina is asking a key question for conservation initiatives worldwide: what baselines do we choose? Do we want ecosystems to look like what it did in 1990 or 1890? Or back further? Often, however, such research is hampered by a simple lack of data.

Red-tailed tropicbird (Phaethon rubricauda) is considered Least Concern. Photo by: Carl Safina. |

Of course, such debates are predicated on the possibility of actually being able to effectively manage overfishing, something that continues despite decades of research and calls to action.

For Ainley, the answer isn’t so much tighter management but “large-scale marine protected areas actually placed where the fishing is good.” In other words, protected areas need to cover abundant regions; for example he says that the only answer to saving the world’s penguin species is to create protected areas that cover their entire foraging range, thus cutting off fisheries from some choice fishing grounds.

“In practice, given the huge dependency of fishing for protein and jobs, whether or not it can be accomplished in my mind is doubtful,” he says.

But Safina strikes a more hopeful attitude, noting that we have to start somewhere.

“These studies are the hope. Fifty years ago, this topic stood no chance of even being raised. The first step toward solving a problem is recognizing it,” he says, adding, “Seabirds need food. Amazing; who knew?”

At stake may be more than just the health of albatross, petrels, and penguins, but the oceans in their entirety.

Are seabirds telling us something?

White terns (Gygis alba) over the Midway Atoll. White terns are listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Carl Safina.

During the past decade, scientists have begun warning that mass extinction could occur in the world’s oceans as well as on land. In fact, according to a recent report by the International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO) the combined impacts of overfishing, pollution, and overfishing are changing the very chemical and ecological nature of our oceans. The bleak report found that if nothing is done, these human impacts will lead to a massive decline in species. The drops in seabirds populations around the world may be considered an early warning sign, since scientists view seabirds as key indicators of ocean health.

“Seabirds are found across all of the world’s oceans, are well-known, relatively easy to monitor, and are sensitive indicators of ocean health,” explains Butchart. “They act as the marine equivalent of canaries in the coal mine because they respond to many of the most important threats to the marine environment: over-harvesting, invasive species, pollution and climate change.”

Arguably the most famous of extinct seabirds, the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was killed off by overhunting and egg collecting. Painting by: Johannes Gerardus Keulemans. |

Because seabirds are the world’s most imperiled family of birds, because nearly half of seabirds are in decline, and because those species most connected to the seas—albatross, petrels, and penguins—are also the most endangered, it would be logical to conclude that the seas are in trouble indeed.

Many of the problems that plague seabirds also imperil other marine species and even people. For example, says Butchart, moving fisheries towards sustainability would help people as much as it does the birds.

“Managing fisheries unsustainably not only denies future generations of people from using these food supplies, but also has detrimental impacts on other biodiversity, including seabirds. Ensuring that harvesting is sustainable provides long-term benefits both to people and nature.”

Many poor people depend on seafood as their primary source of protein, but these sources are vanishing as commercial and foreign fleets plunder the ocean’s waters.

Mitigating pollution, whether nitrogen, oil, or plastic, would certainly benefit thousands of other marine species beyond seabirds, some of which have never even been described by scientists. Finally, climate change, which many scientists say is the biggest threat to humanity today, could also swamp seabird islands and in some cases decimate prey. Saving seabirds may go a long way in preserving not only the wildness of the sea, but the well-being of humanity.

For Safina the reasons behind saving seabirds need not be so self-indulgent. He says that seabirds should be protected: “Because they populate the ocean and coasts. Because they belong there. Because they are beautiful and keep us company.”

Gray-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma) off South Georgia. This albatross is listed as Vulnerable. Photo by: Carl Safina.

King penguin crowd. Photo by: Carl Safina.

Northern royal albatross (Diomedea sanford) in flight. The species is considered Endangered. Photo by: Carl Safina.

A giant petrel feeds on a seal in South Georgia. Photo by: Brocken Inaglory.

Related articles

Penguins face a slippery future

(09/26/2012) Penguins have spent years fooling us. With their image seemingly every where we turn—entertaining us in animated films, awing us in documentaries, and winking at us in commercials—they have made most of us believe they are doing just fine; the penguin’s charming demeanor has lulled us into complacency about their fate. But penguin populations are facing historic declines even as their popularity in human society rises. Overfishing is decimating some of their prey species, climate change is shifting their resources and imperiling their habitat, meanwhile pollution, such as oil spills, are putting even healthy colonies at risk. Now, a young organization, the Global Penguin Society (GPS), is working to save all of the world’s 18 penguin species by working with scientists, governments, and local communities.

World failing to meet promises on the oceans

(06/14/2012) Despite a slew of past pledges and agreements, the world’s governments have made little to no progress on improving management and conservation in the oceans, according to a new paper in Science. The paper is released just as the world leaders are descending on Rio de Janeiro for Rio+20, or the UN Summit on Sustainable Development, where one of the most watched issues is expected to be ocean policy, in part because the summit is expected to make little headway on other global environmental issues such as climate change and deforestation. But the new Science paper warns that past pledges on marine conservation have moved too slowly or stagnated entirely.

Over 500 dead penguins wash up in Brazil, cause under investigation

(07/17/2012) In recent weeks, 512 Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) have washed up dead in Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. Although badly composed, researchers do not see any obvious signs why the penguins died, especially in such numbers. Marine biologists are currently performing autopsies on carcasses and hope to determine cause of death within a few weeks.

Whole Foods bans ‘red’ fish from its stores

(04/10/2012) Whole Foods has announced it will be the first grocery chain in the U.S. to no longer sell any seafood in the “red.” Based on sustainability ratings by the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Blue Ocean Institute, fish labeled red are those that are considered either overfished or fished in a manner that impacts other species or damages marine ecosystems. Beginning Earth Day, April 22nd, Whole Foods will no longer be selling Atlantic halibut, grey sole, skate, octopus, tautog, sturgeon, among others. Already, the store doesn’t sell some unsustainable catches such as bluefin tuna and orange roughy.

Carbon emissions paving way for mass extinction in oceans

(03/05/2012) Human emissions of carbon dioxide may be acidifying the oceans at a rate not seen in 300 million years, according to new research published in Science. The ground-breaking study, which measures for the first time the rate of current acidification compared with other occurrences going back 300 million years, warns that carbon emissions, unchecked, will likely lead to a mass extinction in the world’s oceans. Acidification particularly threatens species dependent on calcium carbonate (a chemical compound that drops as the ocean acidifies) such as coral reefs, marine mollusks, and even some plankton. As these species vanish, thousands of others that depend on them are likely to follow.

Washing clothing pollutes oceans with billions of microplastics

(02/14/2012) Washing synthetic clothes—such as nylon, polyester, and acrylic—is polluting the oceans with billions of microplastics: plastics that measure less than one millimeter. It may sound innocuous, but research has shown that these microplastics are accumulating in marine species with unknown health impacts, both on the pollution-eating species and the humans who consume them.

(06/11/2012) He is so long-lived that he has surpassed all expectations, touching hearts throughout the American continent, bringing together scientists and schools, inspiring a play and now even his own biography. B95 is the name of a rufus red knot (Calidris canutus rufus), a migratory bird that in his annual journeys of 16,000 kilometers (9,940 miles) each way from the Canadian Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, in Argentina, has flown a distance bigger than the one between the Earth and Moon.

Why bird droppings matter to manta rays: discovering unknown ecological connections

(06/04/2012) Ecologists have long argued that everything in the nature is connected, but teasing out these intricate connections is not so easy. In fact, it took research on a remote, unoccupied island for scientists to discover that manta ray abundance was linked to seabirds and thereby native trees.

b>Photos: New Zealand oil disaster kills over 1200 birds to date

(10/16/2011) According to the New Zealand government an oil spill from a grounded container ship in the Bay of Plenty has killed 1,250 seabirds with hundreds of others in rescue centers. However, conservationists say the avian death-toll is far higher with most contaminated birds simply vanishing in the sea. “The number of birds being found washed up on the beaches will be a very small proportion of the birds being affected,” explained Karen Baird, Seabird Conservation Advocate with NGO Forest & Bird.

Bird-killing oil spill New Zealand’s ‘worst environmental disaster’

(10/12/2011) An oil spill from a grounded container ship in New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty is threatening to worsen as authorities fear the ship is breaking up. Already, 350 tons of oil from the ship, the MV Rena, has leaked out with some reaching nearby beaches including a popular holiday spot, Papamoa Beach. To date the spill has killed over 200 birds, including little blue penguins, shags, petrels, albatrosses and plovers. If the ship breaks up and sinks, authorities fear it could release its remaining 1,400 tons into the marine ecosystem.

Sowing the seeds to save the Patagonian Sea

.150.jpg)

(09/07/2011) With wild waters and shores, the Patagonia Sea is home to a great menagerie of marine animals: from penguins to elephants seals, albatrosses to squid, and sea lions to southern right whales. The sea lies at crossroads between more northern latitudes and the cold bitter water of the Southern Ocean, which surround Antarctica. However the region is also a heavy fishing ground, putting pressure on a number of species and imperiling the very ecosystem that supplies the industry. Conservation efforts, spearheaded by marine conservationist Claudio Campagna and colleagues with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), are in the early stages. Campagna, who often writes about the importance of language in the fight for preservation, has pushed to rename the area to focus on its stunning wildlife.

New seabird discovered from Hawaii, but no one knows where it lives

(08/30/2011) Researchers have uncovered a new seabird native to Hawaii stuffed in a museum. Originally identified as a smaller variation of a little shearwater (Puffinus assimilis), DNA tests showed that the bird, which was collected over four decades ago, was in fact a unique species. Named Bryan’s shearwater (Puffinus bryani), the fate of this bird in the wild remains unknown.