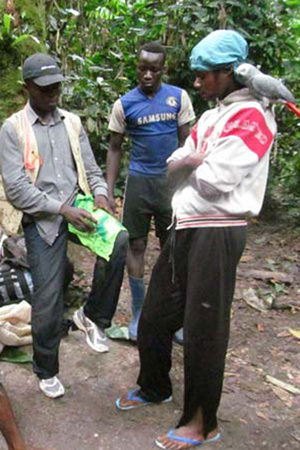

Roger Peet (in blue shirt) posing with Forest Rangers. Photo courtesy of Roger Peet.

Last year, Roger Peet, an American artist, traveled to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to visit one of the world’s most remote and wild forests. Peet spent three months in a region that is largely unknown to the outside world, but where a group of conservationists, headed by Terese and John Hart, are working diligently to create a new national park, known as Lomami. Here, the printmaker met a local warlord, discovered a downed plane, and designed a tomb for a wildlife ranger killed by disease, in addition to seeing some of the region’s astounding wildlife. Notably, the burgeoning Lomami National Park is home to the world’s newest monkey species, only announced by scientists last September.

“I saw something move ahead of us on the transect and raised my binoculars: a monkey was about ten feet up a sapling on one side of the trail, shimmying quickly down. As I watched, it leaned out into the open and looked at me, revealing a distinctive white stripe down its nose: obviously a lesula,” Peet told mongabay.com in a recent interview. “Then it turned its face to the forest and jumped silently into the leaves. I think I probably made a rather embarrassing noise of excitement at that point, which my companions were polite enough to not draw attention to.”

The discovery of a new monkey species—lesula (Cercopithecus lomamiensis)—made headlines worldwide in September and only a few months later, Peet was seeing one for himself.

Plenty for All. Print: Roger Peet. |

Peet, a founding member of Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative, traveled to the remote Congo rainforest as a volunteer for the Harts. He did not come empty-handed, however; the printmaker brought hundreds of bandanas bearing images of threatened, local wildlife.

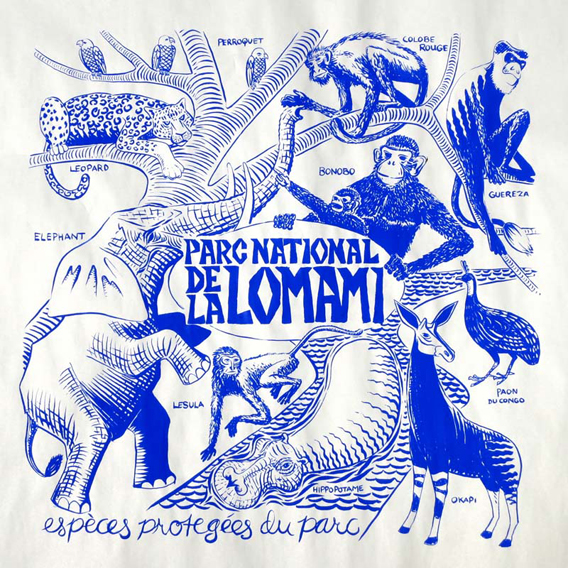

“The goal was to create something that people would want to have, something they’d be curious about, that could be used for multiple purposes, that was durable and functional and educational all at once,” he said. “I did a detailed pen-and-ink drawing of the protected species and screen-printed it onto about 500 bandanas, which I brought with me. I handed them out to the people involved in the park project, to people on the river, village chiefs, fieldworkers and their families, even to a poacher warlord and his gang of heavily armed army deserters.”

The Harts established the TL2 project (TL2 stands for three rivers in region: the Tshuapa, the Lomami, and the Lualaba) to help make Lomami National Park a reality. If established the park would cover 9,000 square kilometers (3,470 square miles) and protect populations of lesulas, bonobos (Pan paniscus), forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), lowland bongos (Tragelaphus eurycerus eurycerus), and okapis (Okapia johnstoni).

“The area represents probably Congo’s last best chance at a new national park,” Peet says. “It’s a stretch of forest that is mostly uninhabited, and that is far enough away from infrastructure to make some of the pressures that other Congolese forests face nonexistent: there’s no commercial logging, no rare-metal mining, and only a little bit of wildcat diamond extraction going on.”

Unlike past parks in the DRC—which were the decree of dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko Lomami National Park—Lomami is being built from the ground-up with community participation. Although remote, the park and its wildlife still face a number of perils.

“Entrenched commercial interests continue to threaten the wildlife of the park through large-scale hunting for meat and through the poaching of protected species. In Obenge, the remote village where I stayed, you could see clearly how the commercial exploitation of certain species helped to destroy the forest. First, the valuable species like elephants and bush pigs would be hunted out of an area. […] In their absence people cut more trees and plant more fields, and then they have to go further into the forest to hunt. That’s how the process perpetuates itself,” explains Peet.

Although home to many endangered species and tracts of magnificent forest, the DRC is also one of the world’s poorest and most war-torn nations. Decades of civil war have left people resilient, generous, and paranoid, according to Peet.

Large unidentified spider in the Congo. Photo by: Roger Peet. |

“So much that we take for granted is absolutely impossible in Congo: for instance, I offered to send a postcard to people who pledged a certain amount to my fundraising campaign, only to find on my arrival that there has been absolutely no mail service at all for more than five years,” Peet says. “People cope. They shrug a lot. They laugh about their circumstances, although it’s a bitter laughter. They rely on each other to help out in difficult situations, they keep their families close, and they share time and resources in ways that were very surprising to a foreigner like me. It must also be said that they often fail to trust one another, accuse each other of terrible and unsubstantiated crimes, and rely on the idea of sorcery to explain a lot of their bad luck and hard times.”

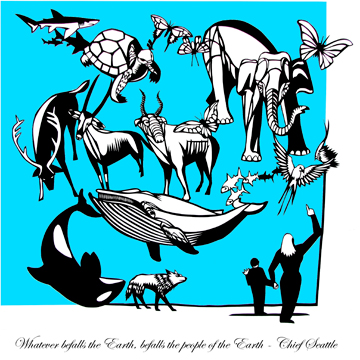

Given the rising warnings of global environmental crises, from mass extinction to climate change, Peet says he uses his art not only to raise awareness and inspire action, but also as personal “catharsis.”

“It helped me face down the despair that I think a lot of us feel, who pay attention to the state of the world. These days I don’t experience the same kind of overwhelming gloom that I felt for much of the last decade. I’ve stopped taking ecological disaster personally, and that’s made it a lot easier to deal with, since I refuse to look away from it.”

In a February 2013 interview, Roger Peet discussed his recent travels in the Congo Rainforest, the role of art in an age of ecological upheaval, and what it was like to craft designs for Endangered Species condom packages.

INTERVIEW WITH ROGER PEET: ENDANGERED SPECIES ART

Bandana by Roger Peet to promote conservation and wildlife identification in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Click to enlarge.

Mongabay: Why printmaking as your medium?

Roger Peet: What I love about printmaking is its multiplicative and universal quality. Prints made by whatever means are designed to exist in multiples, and to have multiple destinations. They’re much more populist vehicles for ideas than are other forms of art which exist singly, and as such have been part of pretty much every social movement that’s existed since printing began. They diminish the unfortunate aristocratic qualities of art by putting it into more hands. I love the range of qualities printmaking possesses as well. Prints can function as objects of the most precious fine art and also as the crudest distributors of raw image and public expression—sometimes both at once.

Mongabay: What sparked your interest in the natural world?

Roger Peet: I’ve always had my face turned towards nature, for better or worse. I spent my early childhood snorkeling in the Red Sea off Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, and underwent a dramatic transition between the tame woodlands of southern England and the raw southern Arizona desert in my early teens. I lived in Minnesota for a long time in the 90s, where I started noticing smaller things like rock-chewing spiders hewing themselves into the faces off the bluffs, but it was through trips to the forests and mountains of the western U.S. in that same time that I realized, as a sort-of adult, what wild nature was, and what I had been missing. Since then I’ve traveled a lot and experienced a small sliver of the larger world and its forests and oceans and open spaces, and that’s helped me develop a sense of pan-global ecological solidarity with everything, everywhere.

Mongabay: You have a passion for insects. What draws you to animals that most people either ignore or abhor?

Unidentified butterfly. Photo by: Roger Peet. |

Roger Peet: I love insects because they are there. They will put up with your inspection, will submit to crawling on a proffered finger and most often not bite or sting. When all the other fauna are distant and in poor focus, insects are intimate, near at hand, and comparatively tame. I spend a lot of time thinking about that recently lost world of naive creatures, in places where human pressure has yet to penetrate, and I find that insects are the most everyday entry into such a cultural space that it’s possible for most people to experience. Insects are motive life that you can touch, that you can gently grip and inspect with little need for specialized tools or skill. They’re not usually food, and not typically of commercial value, and as such they exist outside of culture, in a rare space away from most of human interest. They’re also enormously instructive as regards the history of life, of predation, trap-making, flight, and sex.

Mongabay: As an artist, do you view your work as a form of environmental activism?

Roger Peet: Absolutely. I think the best activism aims to be educational first, to shock thoughts out of their comfortable ruts, and that’s my fondest hope for the art that I make. That said, I’m aware that it’s a very comfortable, withdrawn form of activism that doesn’t face much in the way of beatings and arrests. I try to temper what I encourage with what I’m willing to do myself.

Mongabay: Much of your artwork has an urgent, almost tragic tone to it. Does this reflect your view of our current environmental situation?

Roger Peet: Yes it does. I have now come to grips with a lot of the terrible things that make up the state of the world, things that used to keep me in a constant state of low-level trauma. I arrived at an understanding of the contemporary crisis of biodiversity in a more-or-less backwards way, starting out learning about the global pleistocene extinctions and their association with human activities. Doing a lot of reading on that ever-controversial subject caused me to realize exactly how much has already been lost, and in how short a span of time. Then I extended my reading forward into the early modern period and the great global biological mixing process which is referred to as the Columbian exchange, and then past that into the exponentially accelerated destruction of the present day. The upswinging curve of rates of extinction became a source of almost paralyzing horror for a long time.

‘Whatever befalls the Earth, befalls the people of the Earth’ – Chief Seattle. Print: Roger Peet. |

I think that horror is best summed up in a quote from biologists Michael Soule and Bruce Wilcox: “The end of speciation for most large animals rivals the extinction crisis in significance for the future of living nature.” As [Bruce Wilcox and I] said in 1980, ‘Death is one thing, an end to birth is something else’. Making art about that sort of thing was cathartic. It helped me face down the despair that I think a lot of us feel, who pay attention to the state of the world. These days I don’t experience the same kind of overwhelming gloom that I felt for much of the last decade. I’ve stopped taking ecological disaster personally, and that’s made it a lot easier to deal with, since I refuse to look away from it.

Mongabay: I have to ask, what’s it like developing artwork for condoms? Will you tell us about this unique project?

Roger Peet: The Endangered Species condoms are a project of the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the foremost powerhouses of activism in support of biodiversity and of endangered species. What it consists of is packaging condoms inside small, attractive boxes printed with images of endangered creatures and accompanied by little two-line rhyming zingers that associate using a condom with preserving species: “In the sack? Save the Leatherback!” being one example. It’s a neat project on many levels, not least for its attempt to make a dire subject fun. The interior of each box contains a short blurb about each particular animal, and a paragraph that associates mass extinction with human population increases. For me, this is an unavoidable truth, but it’s very controversial, and there are a lot of people who find it dangerous and insulting to associate population with ecological disaster. The specter of eugenics, of race-based population control, is still very present, and for some any talk of population control tends in that direction. I believe, and I think the Center would agree, that the situation has reached such a point of crisis that a sensitive, principled discussion of the effects of 7 billion people on a small blue planet needs to take place, and to take place now. These condoms are a tiny step towards that debate. They make people laugh, which is crucial: it’s easier to talk about bad news if you can have a chuckle while you’re at it.

My colleague Amy Harwood was working for the Center last year, and approached me to see if I would be interested in designing a second round of images for the project. I was, of course, thrilled at the opportunity, and backed up against a looming deadline I thrashed out six new designs out of cut-paper in a week. The animals were the Leatherback Turtle, the Snowy Plover, the Dwarf Seahorse, the Hellbender Salamander, the Florida Panther, and the Polar Bear. The Center came up with the rhyming couplets that accompany the images, and the boxes were laid out by designer Lori Lieber.

INTO THE CONGO

Camera trap photo of new species of monkey from TL2 region: the lesula. Here the monkey strikes was Peet says is a characteristic pose on a termite mound. Photo by: TL2.

Mongabay: How did you end up in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a place few Americans ever see?

Roger Peet: I had been planning on returning to school to search out some sort of credential that would enable me to go to interesting places and do interesting things. I was accepted into a Visual Anthropology program in the UK, but after realizing that I would probably have to back into debt to pay for it, I balked—I’ve already spent a decade getting out from under one load of that, and I’m never going back. In the aftermath of that decision I was casting around for opportunities, and one day, while reading the excellent Searching for Bonobo in Congo blog of Drs. Terese and John Hart, I decided to toss them an email and see if they were accepting volunteers. There was a quick, affirmative response, and they suggested that I come for three months in the fall. I was flabbergasted—I felt like I’d won the lottery, I would be skipping the middleman and going directly to Congo! A month or so later I proposed the bandana project, which they were enthusiastic about, and we talked over Skype to confirm that I was indeed a comparatively sane, rational human. Six months later I landed in Kinshasa.

Mongabay: What was your impression of the burgeoning Lomami National Park?

Unidentified beetle (Heteroptera). Photo by: Roger Peet. |

Roger Peet: The park is still, at this point, more an idea than a reality. The project to develop it has made great strides forward but faces a lot of big, sharp obstacles in both the immediate and distant futures. As an idea, it’s being enthusiastically presented to the people of the region and to the relevant functionaries in government by an accomplished team of scientists, fieldworkers and researchers. In the field, those workers face opposition from organized forces of commercial bushmeat exploitation, gangs of elephant poachers, and village authorities reluctant to cede authority over their territory to an idea that seems abstract and foreign. In government there’s Congo’s fabled corruption to contend with, which is rightfully legendary, and beyond that there’s the capriciousness of funding and wrangling aid money out of foundations and NGO’s.

That said, the area represents probably Congo’s last best chance at a new national park. It’s a stretch of forest that is mostly uninhabited, and that is far enough away from infrastructure to make some of the pressures that other Congolese forests face nonexistent: there’s no commercial logging, no rare-metal mining, and only a little bit of wildcat diamond extraction going on.

The project is especially significant in light of the manner in which the other national parks in Congo were established, in 1969, by dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. He issued an executive decree stating that these areas here, here, and here were now parks, and that anyone living within their boundaries had one month to pack up and leave before the army came to burn their villages and force them out at gunpoint. The Lomami Park is being promoted in a precisely opposite fashion, with a view towards creating in the local population a vested interest in the function and maintenance of the park and its wild nature. They call it community conservation, and it’s a lot of hard work. The forest that the park encompasses is huge and rough, beautiful and dangerous and almost trackless. It’s a difficult place to move around, which makes it difficult to patrol and difficult to monitor populations of animals and birds. The people doing that work are doing an amazing job.

Mongabay: Will you tell us about the bandanas you brought to the Congo? What was the goal of this project?

Roger Peet: When I first talked to the Harts about volunteering, I mentioned that I was an artist with an interest in ecology. They looked at my website and wrote back that my art reminded them of a poster that had been printed and distributed in Congo in the 70’s, illustrating some of the rare and spectacular creatures of the region. I noted from reading their blog, that one tool that they used to promote the park was a laminated two-sided color photocopy of images of Congo’s protected species. I immediately thought, on seeing that, that I could do better. How could that information be presented in a way that it would be visible daily in the context of a remote Congolese village, not just on a more-or-less useless slick plastic artifact?

My friend and collaborator Amy Harwood came up with the idea of a bandana, which was a stroke of genius—a bandana with images of the park’s protected species printed on it, in bright colors. The goal was to create something that people would want to have, something they’d be curious about, that could be used for multiple purposes, that was durable and functional and educational all at once. I did a detailed pen-and-ink drawing of the protected species and screen-printed it onto about 500 bandanas, which I brought with me. I handed them out to the people involved in the park project, to people on the river, village chiefs, fieldworkers and their families, even to a poacher warlord and his gang of heavily armed army deserters.

Mongabay: How did locals respond to your bandanas?

Outreach with bandanas. Photo by: Roger Peet. |

Roger Peet: People responded pretty well, I thought. Everyone I gave one to was certainly eager to get one, and several of the park project workers told me I should have brought more—when I passed back through Opala, the territorial capital, on my way back to Kisangani, people there noted that when they wore them out and about, everyone they met with asked what they were, and they were then able to use them to talk about the park. In Obenge, the park workers wore them as a sort of uniform, or a badge of allegiance or participation, something to mark out their involvement in the project. The women of the project and the wives of project workers were particularly enthusiastic about them. There was a lot of quite impressive color-coordination to be seen, especially at church events when people tended to put on their finer garments and use the bandanas as headscarves.

Mongabay: Last year scientists announced the discovery of a new species of monkey in the region, which made global news. Will you tell us about seeing the lesula in person?

Roger Peet: The lesula is an interesting beast. It’s a terrestrial monkey, and doesn’t seem to go up very far into the canopy, at least not for any length of time. We often saw them on camera traps perched delicately on the weird brown umbrellas of termite mounds. Its close relation the owl-faced monkey is similarly terrestrial. Why it is that these species prefer the ground to the forest is subject to discussion, but it’s certainly interesting to me to consider the parallels between their behaviour and that of our own tree-rejecting primate ancestors.

When we were in the forest, monkeys were the most common fauna. A broad variety of species move through different levels in the canopy, exploiting the same fruit resources and keeping a cooperative eye out for predators. Red colobus, black colobus, Angola guereza, red-tailed, and Wolf’s monkeys were all varyingly common and active. I slowly acquired a familiarity with their individual calls and chirps, and I got into a habit of rising before sunrise to sit out in the forest and make recordings of their dawn choruses. During these recordings I heard the cry of the lesula numerous times, a low, slightly drawn-out and mournful hoot. I’d more or less given up on spotting one, as I only ever heard their calls at dawn and we were out walking during the morning and early afternoon. On my last trip to the forest, we had rounded the corner of the most distant part of the zone of study in the late afternoon. In doing so we spooked a group of guineafowl, who beat up into the canopy with a drumroll of fast wingbeats. Up above us a group of monkeys started to take flight. They leapt wildly from their perches, arcing out into the air and bashing into clumps of foliage, swinging their limbs through and springing away again. I saw something move ahead of us on the transect and raised my binoculars: a monkey was about ten feet up a sapling on one side of the trail, shimmying quickly down. As I watched, it leaned out into the open and looked at me, revealing a distinctive white stripe down its nose: obviously a lesula. Then it turned its face to the forest and jumped silently into the leaves. I think I probably made a rather embarrassing noise of excitement at that point, which my companions were polite enough to not draw attention to.

What’s truly fascinating to me about that experience was that it showed that the lesula was moving through the forest with the other monkeys, occupying the lowest stratum of the forest. Sometimes duikers (forest antelope) will follow troops of monkeys through the forest, opportunistically picking up fruit that the monkeys and hornbills knock loose from above. In this situation, it was the lesula taking advantage of that resource.

PERILS

Rangers burn a poacher’s camp. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Mongabay: The DRC has known incredible suffering from war and poverty over the last few decades. What was your impression of how people survive during such times?

Roger Peet: The infamous Article 15 of the short-lived post-independence Empire of Kasai in southeastern Congo stated to the populace: Fend for yourselves. This was a cynical attempt to stave off the flood of demands from a province full of people desperate for the amenities a state was supposed to provide, and opened the floodgates of corruption. Mobutu essentially enshrined this principle as law, ignoring the subsequent pillage of society and its infrastructure by his ill-paid army and the legions of bureaucrats on-the-take that made up his government. When the war hit, a country already in tatters was given a further brutal ravaging by waves of armed maniacs, a conflict which hasn’t really finished, but is instead currently at what could best be called a low ebb. So much that we take for granted is absolutely impossible in Congo: for instance, I offered to send a postcard to people who pledged a certain amount to my fundraising campaign, only to find on my arrival that there has been absolutely no mail service at all for more than five years. People cope. They shrug a lot. They laugh about their circumstances, although it’s a bitter laughter. They rely on each other to help out in difficult situations, they keep their families close, and they share time and resources in ways that were very surprising to a foreigner like me. It must also be said that they often fail to trust one another, accuse each other of terrible and unsubstantiated crimes, and rely on the idea of sorcery to explain a lot of their bad luck and hard times. Sorcery was omnipresent and very hard for me to get a grip on. Some of the only heartfelt disagreements I had with the people I was working with were over my disbelief in the power of magic to affect people and things.

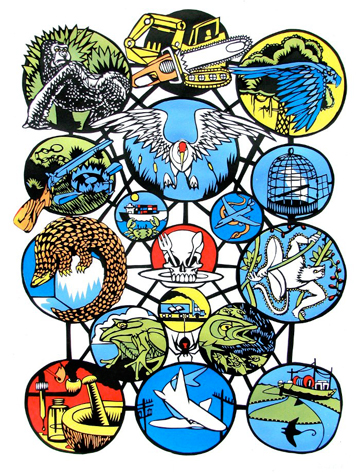

Mongabay: What are the major threats to the proposed park?

Roger Peet: The biggest threat is corruption among the officials charged with chaperoning it towards official recognition. The venality and greed that the TL2 project has had to contend with would have crushed less driven people, and to see John and Terese maneuver so skillfully around the grabbing hands that oppose them is pretty impressive. Entrenched commercial interests continue to threaten the wildlife of the park through large-scale hunting for meat and through the poaching of protected species. In Obenge, the remote village where I stayed, you could see clearly how the commercial exploitation of certain species helped to destroy the forest. First, the valuable species like elephants and bush pigs would be hunted out of an area. Those species are terrible trouble for farmers, uprooting and trampling crops with a ruthless sort of enthusiasm. In their absence people cut more trees and plant more fields, and then they have to go further into the forest to hunt. That’s how the process perpetuates itself.

Mongabay: You met poachers and warlords during your travels. What were these encounters like?

Colonel Thoms leaving. Photo by: Roger Peet. |

Roger Peet: The major de facto authority in the park region for much of the past ten years has been a man named Colonel Thoms. Thoms comes from a village in the region, and rose to a sort of power during the war, and its aftermath, by being the most ruthless and well-armed individual around. He treated the villages in the park area like open-air markets, arriving at whim to procure whatever he wanted—women, liquor, food, porters, and sport. He raped a lot of women. He humiliated people. He hunted elephants ruthlessly for their ivory and sold their tusks through contacts in the army to middlemen that sent them on to China, Malaysia and Vietnam. When he became too much of a public liability in the latter half of the 00’s, he was tricked into traveling to Kisangani, arrested, put on trial for rape, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. He spent a year in prison before he escaped, presumably with help from his army contacts, and returned to the forest.

During my time at camp, the Obenge boy’s soccer team left to play an away game at a village about two days walk away. While they were there, they encountered Thoms, who grilled them about reports he’d heard regarding the park guards harassment of the population. He’d heard that they had been stealing and threatening people. Luckily the team was being escorted by a man who was an ally to the park project, who carefully disabused Thoms of that notion. Thoms replied that in that case he’d be coming to Obenge in two weeks to have a face-to-face discussion with the park workers and the guards about the situation. No-one believed this when the team returned to relate it. Everyone assumed that he would stay well away from a group of heavily armed agents of the state that locked him up.

I was down by the river one day about ten days later, sketching monkeys, when a pirogue went past with four people I didn’t recognize in it, spaced oddly along its length. The another pirogue went past, closer this time, and I could see that some of the men in it had guns. I waved, for lack of a better idea, and the heavily-bearded fellow in the prow swatted his hand at me and spat. I thought—Huh, maybe that was Colonel Thoms. Then a park worker came sprinting down the muddy steps outside the bamboo palisade to tell me, breathlessly, that the poachers had arrived.

They stayed two days, Thoms and two deserters from the national army who were fleeing the war in the east, along with four other men and the wife of one of the deserters. Six men had automatic rifles, and one a bow and a quiver full of poisoned arrows. I wasn’t allowed to go from camp into the village to meet Thoms, though I did try—’No, he’s a barbarian, they said. You stay here.’

The Process. Print by: Roger Peet. |

Thoms had come to make his case. During two days of meetings, he explained to the Lieutenant and to Pablo and Maurice (the two top TL2 workers) that he wanted to put an end to the rumors that were flying back and forth. He knew that people were forging his signature on threatening letters slipped into the camp at night, letters saying he was coming to burn the camp and kill everyone if they didn’t leave. He also knew that the reports that he’d been receiving of harassment by the park-guards weren’t true. He proposed a truce—he would stay in the forest to the southeast and southwest of the camp, avoiding the study area, and refraining from offering opposition to the park, but he would continue to poach elephants. He claimed that there was nothing else that he knew how to do, and that he had children to feed and put through school. He promised not to harass local populations, and requested that if the two armed groups met in the forest that they would greet one another and go on their mutual ways. The TL2 workers could do little but agree with his proposition. He also said that he knew they had a white person in camp. He’d never met a white person, but he knew they had secret cameras that could take pictures of you without your knowledge. He didn’t know what he’d do if he met one: perhaps he’d kidnap them, he said, and laughed. I did have the opportunity to wave goodbye as he left the next day. Salud, we both said with a smile as his pirogue was rowed slowly past, upstream.

Mongabay: You also witnessed tension over the development of the park. Will you tell us about that?

Roger Peet: Among the young people of Obenge, there is a lot of consensus that the park is a good idea. Some of the young men are learning how to use GPS units, to take measurements and photos and field notes and to knit all that data together in a way that it can be collated and utilized by scientists. Some are working as porters. The proposed relocation of Obenge sounds like magic to them—new houses, a radio-telegraph station, closer to a town and to a market where crops could be sold and money be spent. The older generation is much less enthusiastic. Many of them have ended up in Obenge specifically because of its reputation as a lawless frontier zone where there is no state, and no enforcement of law. Many are fleeing shady pasts, or bad marriages, or serious mistakes. There is tension in the village, and there’s a lot of dirty tricks being played by people who want to see the park project fail. This runs the gamut from sorcery to threatening letters to vicious rumor and sabotage. It’s quite intense. The current chief was installed as such by Colonel Thoms, who came to town and deposed the previous chief for the crime of confiscating illegal weaponry from villagers. He had that ex-chief publicly tortured for a week in the center of the village. The new chief and her family are thus in thrall to Thoms, as well as to other commercial bushmeat and poaching interests. The park project, however, has funding that they don’t, resources they don’t and a goal that they don’t. It’s a complicated situation, but I think that the park project can succeed if it can defeat corruption at higher levels of government.

Mongabay: How will your experience in the Congo impact your artwork going forward?

From above. Print by: Roger Peet.

Roger Peet: I’m currently in Eastern Oregon at a month-long arts residency where I’m trying to forge some of the ideas and images that I acquired in Congo into art. There’s a lot to synthesize. Biology has to be knit to politics, history to potential, persistence to despair. I’ve got a million ideas that I have to ruthlessly winnow over the next four weeks! One idea that I’m toying with is to make big block-prints that incorporate design elements from Congolese money, both the contemporary notes and those from the Belgian and Mobutu eras. Congo’s money features its wildlife prominently, so talking about the issues facing wild nature and people in the Congolese context and within the larger world economy would fit pretty well with that idea. I’m also working on some sort of narrative of the trip, trying to incorporate some of my personal family history into my experiences: my father was a mercenary pilot for the CIA in Congo in the post-independence period, and also Mobutu’s personal helicopter pilot for a short stint.

I didn’t even get into the enormous crashed aeroplane that we found in the forest, something no-one had stumbled across until us, five to ten years after the fact. So many crazy stories. Such an amazing place.

Forest robin. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Bonobo in TL2 area. Photo by: TL2.

Rose chafer (Chelorrhina polyphemus spp.). Photo by: Roger Peet.

Forest elephant and calf on camera trap. Photo by: TL2.

Unidentified moth. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Ceremony in the Congo. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Lesula on camera trap. Photo by: TL2.

Leopard on camera trap. Photo by: TL2.

Discovering a downed plane in the forest. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Roger Peet working on tombstone for ranger who perished from disease. Photo by: Roger Peet.

Map of TL2 region.

Some endangered wildlife of TL2

Black crested mangabey (Lophocebus aterrimus), Near Threatened

Bonobo (Pan paniscus), Endangered

Congo peacock (Afropavo congensis), Vulnerable

Forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), lumped with savannah elephant: Vulnerable

Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), Vulnerable

Leopard (Panthera pardus), Near Threatened

Lowland bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus eurycerus), Near Threatened

Okapi (Okapia johnstoni), Near Threatened

Western red colobus (Procolobus badius), Endangered

Related articles

Remarkable new monkey discovered in remote Congo rainforest

(09/12/2012) In a massive, wildlife-rich, and largely unexplored rainforest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), researchers have made an astounding discovery: a new monkey species, known to locals as the ‘lesula’. The new primate, which is described in a paper in the open access PLoS ONE journal, was first noticed by scientist and explorer, John Hart, in 2007. John, along with his wife Terese, run the TL2 project, so named for its aim to create a park within three river systems: the Tshuapa, Lomami and the Lualaba (i.e. TL2), a region home to bonobos, okapi, forest elephants, Congo peacock, as well as the newly-described lesula.

Innovative conservation: bandanas to promote new park in the Congo

(07/16/2012) American artist, Roger Peet—a member of the art cooperative, Justseeds, and known for his print images of vanishing species—is headed off to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to help survey a new protected area, Lomami National Park. With him, he’ll be bringing 400 bandanas sporting beautifully-crafted images of the park’s endangered fauna. Peet hopes the bandanas, which he’ll be handing out freely to locals, will not only create support and awareness for the fledgling park, but also help local people recognize threatened species.

In search of conflict-free tin from the Congo

(02/12/2013) I am excited to be returning to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) this weekend. My previous visit in January and February of last year was with a delegation aiming to analyze and audit the first conflict-free supply of tantalum from the DRC via the Solutions for Hope ‘closed pipe’ project. The success of Solutions for Hope, which Motorola Solutions helped to found with AVX, proved that it is possible to source minerals from the DRC through a secure, traceable chain of custody from mine to smelter. This trip extends from that work with the Conflict-Free Tin Initiative (CFTI).

Okapi Conservation Project wins mongabay’s 2012 conservation award

(12/06/2012) A group that works to protect the rare okapi, a type of forest giraffe found only in the Congo Basin, has has won mongabay.com’s 2012 conservation award. The Okapi Conservation Project has been working to protect the okapi and its habitat in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for 25 years. The group was instrumental in establishing the Okapi Wildlife Reserve, a 13,700-square-kilometer tract of wilderness in the Ituri Forest of northeastern DRC. While the Okapi Conservation Project has had a long track record of success, earlier this year it was devastated by a brutal attack on the reserve’s headquarters. Two wildlife rangers were among the six people killed during June 24 assault.

Mountain gorilla population up by over 20 percent in five years

(11/13/2012) A mountain gorilla census in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park has a population that continues to rise, hitting 400 animals. The new census in Bwindi means the total population of mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) has reached 880—up from 720 in 2007—and marking a growth of about 4 percent per year.

(11/08/2012) In 2002 the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) announced a moratorium on commercial logging in a bid to save rapidly falling forests, however a new report by Global Witness alleges that industrial loggers are finding a way around the logging freeze. Through unscrupulous officials, foreign companies are abusing artisanal permits—meant for local community logging—to clear-cut wide swathes of tropical forest in the country. These logging companies are often targeting an endangered tree—wenge (Millettia laurentii)—largely for buyers in China and Europe.

‘The ivory trade is like drug trafficking’ (warning graphic images)

(11/05/2012) For the past five years, Spanish biologist Luis Arranz has been the director of Garamba National Park, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Arranz and a team of nearly 240 people, 140 guards among them, work to protect a vast area of about 5,000 square kilometers (1,930 square miles) of virgin forest, home to a population of more than 2.300 elephants that are facing a new and more powerful enemy. The guards are encountering not only bigger groups of poachers, but with ever more sophisticated weapons. According to Arranz, armed groups such as the Lord’s Resistance Army from Uganda are now killing elephants for their ivory.

NASA satellites catch vast deforestation inside Virunga National Park

(10/03/2012) Two satellite images by NASA, one from February 13, 1999 and the other from September 1, 2008 (see below), show that Virunga National Park is under assault from deforestation. Located in the eastern edge of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) the park has been assailed by entrenched conflict between rebels and government forces, as well as slash-and-burn farming, the charcoal trade, and a booming human population.

British government comes out against drilling in Virunga National Park by UK company

(10/01/2012) The British government has come out in opposition against oil drilling plans by UK-based, SOCO International, in Virunga National Park, reports Reuters. The first national park established on the continent, Virunga is home to one of only two populations of mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in the world. In March of this year, two oil exploratory permits came to light granting SOCO seismic testing inside the park by the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Conflict and perseverance: rehabilitating a forgotten park in the Congo

(09/19/2012) Zebra racing across the yellow-green savannah is an iconic image for Africa, but imagine you’re seeing this not in Kenya or South Africa, but in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Welcome to Upemba National Park: once a jewel in the African wildlife crown, this protected area has been decimated by civil war. Now, a new bold initiative by the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), dubbed Forgotten Parks, is working to rehabilitate Upemba after not only decades of conflict but also poaching, neglect, and severe poverty.

Rodents have lowest diversity in primary forests in the Congo

(09/17/2012) For many animal families, diversity and abundance rises as one moves away from human-impacted landscapes, like agricultural areas, into untouched places, such as primary rainforests. However, a new study in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science, shows that the inverse can also be true. In this case, scientists working in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) Maskao Forest found that both rodent diversity and abundance was lowest in primary forest.