The Maya city of Tulum. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Researchers have garnered further evidence for a smoking gun behind the fall of the great Maya civilization: deforestation. At the American Geophysical Union (AGU) conference, climatologist Ben Cook presented recent research showing how the destruction of rainforests by the Mayan ultimately led to declines in precipitation and possibly civilization-rocking droughts. While the idea that the Maya may have committed ecological-suicide through deforestation has been widely discussed, including in Jared Diamond’s popular book Collapse, Cook’s findings add greater weight to the theory.

Modeling by Cook and his colleagues showed that replacing rainforest with agriculture led to increasing reflectivity of the land surface, known as albedo. This increase in reflectivity changed rainfall patterns.

“Farmland and pastures absorb slightly less energy from the sun than the rainforest because their surfaces tend to be lighter and more reflective,” explained Cook, with NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York City, in a press release from AGU. “This means that there’s less energy available for convection and precipitation.”

Prior to the arrival of Columbus, the central American empire cut forests far-and-wide to feed a growing population. However, they didn’t realize that they were exacerbating their own decline. By a little after 900 AD the Maya civilization had largely collapsed.

Aerial view of Amazon rainforest landscape scarred by open pit gold mines. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

To tease out the smoking gun, Cook turned to the most detailed and accurate reconstructions yet of land-cover in the Yucatan peninsula before and after the collapse. The reconstruction shows that only a small percentage of forest survived in the Yucatan Peninsula between 800 and 950 AD.

Running climate models with the new data, Cook saw a clear change: precipitation fell by 10 to 20 percent generally. The effect was largest around the big Mayan population centers. During the Maya’s last stand between 800 and 950 AD rainfall fell 20 percent. The models also agree with precipitation records of the period taken from cave stalagmites.

Still, Cook says it’s likely that a number of impacts caused the decline of the Maya.

“I wouldn’t argue that deforestation causes drought or that it’s entirely responsible for the decline of the Maya, but our results do show that deforestation can bias the climate toward drought and that about half of the dryness in the pre-Colonial period was the result of deforestation,” he says.

But a mega-drought would have crippled agriculture for a growing population, dried up vital water sources, and likely destabilized political and religious authority.

Cook’s findings buttress a previous study last year by Robert Oglesby, which also argued that deforestation played a significant role in the Maya collapse.

Following the Maya collapse, the Aztec civilization rose in the region. However, that civilization fell to smallpox and a small Spanish invasion force in 1519. Brought by the Europeans, smallpox killed ofd a significant, though highly debated, percentage of the indigenous people. Between 1500 and 1650 AD, forests returned with the population decline.

Scientists in recent years have begun to increasingly link precipitation patterns with tropical forests. A 2005 NASA study found that smoke from burning forests inhibits cloud production, decreasing rainfall. Meanwhile, a 2009 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that historic deforestation in China and India caused a change in the monsoon, decreasing rainfall in China by 10 percent and India by 30 percent. Consequences may range beyond the region where deforestation occurs: according to NASA, the Amazon influences rainfall from Mexico to Texas; the Central American rainforest affects precipitation in the Midwest; and the tropical forests of Southeast Asia impacts rainfall in China and the Balkans. The most radical theory, however, from two Russian scientists, Victor Gorshkov and Anastassia Makarieva, argues that forests are a key driver of global precipitation. Acting as pumps, forests push precipitation from coastal areas into the continental interiors. In other words, a loss of forest may bring drought to continental centers, for example drought in Australia may be explained by the widespread loss of its coastal forests.

Even beyond precipitation, forests provide many services to human-kind: sequestering carbon, preserving the bulk of the world’s biodiversity, providing life-saving medicines, conserving vast freshwater reservoirs, and safeguarding indigenous cultures.

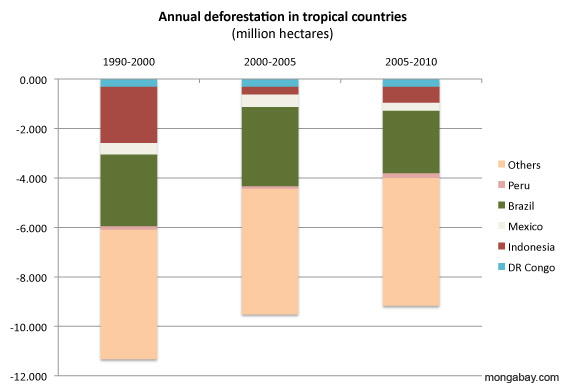

If the intriguing theory that the Maya did themselves in through deforestation holds, it provides a stark lesson to the world today. According to a recent analysis from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) the world has lost 72.9 million hectares of forest between 1990 and 2005, an area twice the size of Germany. Logging, monoculture plantations, large-scale agriculture, mining, fossil fuel industries, roads, and other impacts are largely behind the current decline in the world’s forests.

“We could see these sorts of things happen again,” Cook said pointing to current forest loss in Central America.

Related articles

(12/06/2011) The Brazilian Senate tonight passed controversial legislation that will reform the country’s 46-year-old Forest Code, which limits how much forest can be cleared on private lands. Environmentalists are calling the move “a disaster” that will reverse Brazil’s recent progress in slowing deforestation in the world’s largest rainforests.

(12/06/2011) How to finance a means to reduce deforestation, which contributes emissions equivalent to the entire transport sector combined, has had some encouragement at the UN Climate meeting in Durban this week. An à la carte approach, where no source is ruled out, is emerging, leaving the door open to private sector finance for the first time. And with progress imminent in two other crucial areas of safeguards and reference levels, REDD+, a novel mechanism to halt deforestation, is once more likely to be the biggest winner.

Amazon rainforest loss in Brazil drops to lowest ever reported

(12/05/2011) Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell to the lowest level on record between August 2010 and July 2011 according to preliminary data from Brazil’s National Institute of Space Research (INPE).

Global forest cover lower than previously estimated, says UN

(11/30/2011) Global forest cover, as well as forest loss, is lower than previously estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), according to a new satellite-based assessment that replaces the self-reporting system previously used by the U.N. agency.

Deforestation could be stopped by 2020

(11/28/2011) If governments commit to an international program to save forests known as REDD+, deforestation could be nearly zero in less than a decade, argues the Living Forests Report from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). REDD+, which stands for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, is a program that would pay developing nations to preserve forests for their ability to sequester carbon. Government officials begin meeting tomorrow in Durban, South Africa for the 17th UN climate summit, and REDD+ will be among many topics discussed.

First ever survey shows Sumatran tiger hanging on as forests continue to vanish

(11/10/2011) The first-ever Sumatran-wide survey of the island’s top predator, the Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae), proves that the great cat is holding on even as forests continue to vanish. The study, carried out by eight NGOs and the Indonesian government, shows that the tiger is still present in 70 percent of the forests surveyed, providing hope for the long-term survival of the subspecies if remaining forests are protected.

11 challenges facing 7 billion super-consumers

(10/31/2011) Perhaps the most disconcerting thing about Halloween this year is not the ghouls and goblins taking to the streets, but a baby born somewhere in the world. It’s not the baby’s or the parent’s fault, of course, but this child will become a part of an artificial, but still important, milestone: according to the UN, the Earth’s seventh billionth person will be born today. That’s seven billion people who require, in the very least, freshwater, food, shelter, medicine, and education. In some parts of the world, they will also have a car, an iPod, a suburban house and yard, pets, computers, a lawn-mower, a microwave, and perhaps a swimming pool. Though rarely addressed directly in policy (and more often than not avoided in polite conversations), the issue of overpopulation is central to environmentally sustainability and human welfare.