An interview about orangutan conservation and the complexities of palm oil with Panut Hadisiswoyo and David Dellatore of the Orangutan Information Center and Helen Buckland of the Sumatran Orangutan Society.

Of the world’s two species of orangutan, a great ape that shares 96 percent of man’s genetic makeup, the Sumatran orangutan is considerably more endangered than its cousin in Borneo. Today there are believed to be fewer than 7,000 Sumatran orangutans in the wild, a consequence of the wildlife trade, hunting, and accelerating destruction of their native forest habitat by loggers, small-scale farmers, and agribusiness.

Gunung Leuser National Park in North Sumatra is one of the last strongholds for the species, serving as a refuge among paper pulp concessions and rubber and oil palm plantations. While orangutans are relatively well protected in areas around tourist centers, they are affected by poorly regulated interactions with tourists, which have increased the risk of disease and resulted in high mortality rates among infants near tourist centers like Bukit Lawang. Further, orangutans that range outside the park or live in remote areas or on its margins face conflicts with developers, including loggers, who may or may not know about the existence of the park, and plantation workers, who may kill any orangutans they encounter in the fields.

Sumatran orangutan in North Sumatra |

Working to improve the fate of orangutans that find their way into plantations and unprotected community areas is the Orangutan Information Centre (OIC), a local NGO that collaborates with the Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS). Founded by Panut Hadisiswoyo, OIC runs outreach and education programs to help local people better co-exist with orangutans and the park. Its “OrangUvan,” a bus equipped with a library and a mobile cinema, regularly visits villages to make children and adults aware of conservation efforts and the importance of protecting forests. OIC also operates tree nurseries and replanting programs to help restore livelihoods where unsustainable logging and environmental degradation have pushed villagers to illegally cut timber from the national park. Further, OIC is preparing the next generation of conservationists and ecotourism guides, running how-to workshops on surveying forest conditions and orangutan density, boat handling, nature photography, composting and organic farming, and responsible nature guiding (that doesn’t harm orangutans or the environment). In conjunction with the Orang Utan Republik Foundation, OIC runs a scholarship program for Indonesian University students that aims to help enable them become key members of the conservation movement in Sumatra and inspire others to care for nature and their environment.

OIC Mobile Unit staff in front of one of the OIC Orang-U-Vans. Courtesy of OIC |

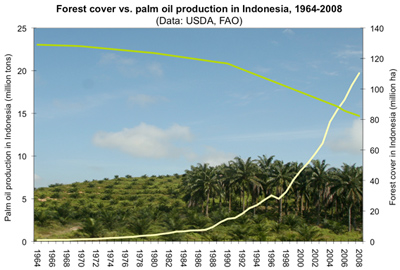

OIC is also working to engage the palm oil industry, a challenge since oil palm expansion is both a leading driver of deforestation and an important source of jobs in the region. While many large palm oil companies are eager to shed the perception that they are a threat to orangutans, plantation developers continue to drive destruction of important orangutan habitat, especially in unprotected areas. Deforestation, as well as drainage of carbon-dense peatlands, is also a huge source of greenhouse gas emissions, undermining claims that palm oil is necessarily a “green” source of fuel and vegetable oil. Indeed, palm oil produced on newly deforested lands is actually the opposite—a larger source of carbon dioxide than conventional fossil fuels. But demonizing all palm oil is neither productive nor fair. Oil palm is the world’s highest yielding oilseed, generating substantially more vegetable oil per unit of land than soy, rapeseed/canola, or corn. Further, the crop has become an important source of income in much of rural Sumatra, while serving as an inexpensive foodstuff for local people and the world.

Replanting a new generation of oil palm in a plantation in North Sumatra. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Is there a way to balance palm oil production and environmental aims? Some environment groups are advocating a ban on all palm oil, but given rising demand for edible oils, especially in China and India, this is an unlikely solution. Other groups, including SOS and OIC, are hopeful that the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a multi-stakeholder body devising a certification standard that aims to improve the environmental performance of palm oil production, could be the path forward, provided the scheme is credible. But credibility is elusive when RSPO members (whom are not necessarily certified palm oil producers; they are only required to pay a membership fee to be part of RSPO) are found to be attempting to game the system, breaking rules and refusing third-party compliance monitoring. Such practices risk turning RSPO into little more than another greenwashing initiative, a concern that has already turned away some potential supporters, including a few major buyers of palm oil who are now seeking other vegetable oil options. Still, OIC believes that in the end a credible RSPO will be better for orangutans and better for business than the alternative—continued destruction of tropical forests and peatlands.

In a series of interviews conducted in Medan and Bukit Lawang (Sumatra) and via e-mail, Panut Hadisiswoyo and David Dellatore of OIC, and Helen Buckland, UK Director of the Sumatran Orangutan Society, talked about their efforts to save the world’s rarest orangutan species as well as the “palm oil paradox.”

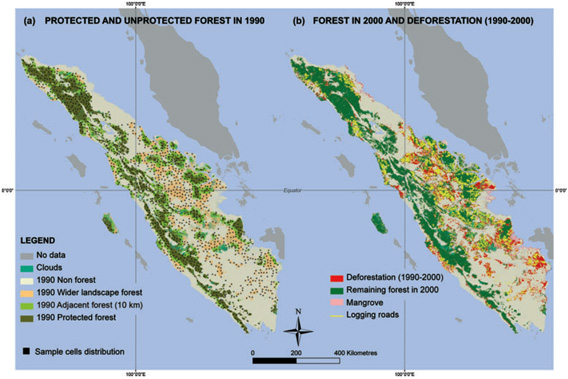

(a) Protected and unprotected forests in 1990 for the main island of Sumatra and the smaller island of Siberut, including adjacent unprotected land lying within 10 km of protected area (PA) boundaries and the wider unprotected landscape, and showing the spatial distribution of the 1264 sample cells (25 km2). (b) Remaining forests in 2000, deforestation and logging trails occurring during the period 1990–2000 (UTM projection, WGS84). Protected areas (PAs) protecting mangroves or created after 2000 are not shown. MAPS available at sumatranforest.org |

Q&A WITH DAVE DELLATORE

Mongabay: What lead you to take an interest in orangutans?

Dave Dellatore, Kelvin Davies from Rainforest Rescue Australia, and Panut Hadisiswoyo in the OIC Besitang forest restoration program area of the GLNP.

|

Dave Dellatore: My first ‘experience’ or memory of orangutans was on a family trip we took to the San Diego Zoo when I was ten or so. We came upon the orangutan enclosure, and I still remember staring at the big male that was there at the time. Since then I’d maintained an unhealthy obsession with apes, starting with enjoying all sorts of terrible films and greeting cards depicting them in unlikely situations. With age and some further research though I came to know how in order to get apes and monkeys to ‘act’, they’re beaten to all hell and deprived of basic needs. So I grew up a bit and started to see them as amazing as they are, living wild in the forest.

I signed up to university as an engineering major, but then on my first day of orientation switched to biology – realizing that I really liked orangutans, so why not work with them for the rest of your life? That was eleven years ago in Pennsylvania, USA; I’m writing this now in Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia, where I’ve been for the past two years now and where I’ll continue to be. And that’s that.

Mongabay: How did you first start working with orangutans?

Dave Dellatore: I nearly failed out of university my first two years. I wasn’t inspired and it just didn’t feel right, so I got to contacting a series of people in the orangutan sector online. I got to talking quite a bit with Dr. Gary Shapiro, then vice-president of the Orangutan Foundation International (and now Founding Director of the Orang Utan Republik Foundation), and after a few months of conversing he recommended I go out to Indonesia to see the orangutans in the wild. So I quit university, took a full-time job to save up, and eventually off I went to Central Kalimantan for six weeks.

I ended up staying for two years, volunteering at their Orangutan Care Centre and Quarantine, helping to take care of the orphaned orangutans and setting up environmental enrichment for the holding cages, eventually graduated to working with the more difficult orangutans that were ‘half-wild’ and required more attention/persistence, and then finally moved to conducting dawn-dusk follows of newly released orangutans in the OF release site.

Entrance to the Gunung Leuser National Park at Bukit Lawang. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

After those two years with much hesitation to leave, decided it would be best for me to have a degree of some sort, so I went back to the US and completed my first degree – doing much, much better than before I’d gone abroad and actually done what I wanted to do.

Then I went on almost immediately to earn a Masters of Science in Primate Conservation from Oxford Brookes University in the UK (which is an excellent program with incredible course leaders). For that I conducted research in Bukit Lawang, Sumatra, on the behavioral health of the population of released orangutans there. And from that, and seeing the negative effects the tourism operation in place there was having on the orangutans, suggested to the Sumatran Orangutan Society / Orangutan Information Centre that they get more involved and start a program there.

From that I was eventually brought on, and now two years later am still here with them and doing all that’s possible to help save the orangutan.

PALM OIL

Mongabay: Do you see engagement with or opposition to palm oil companies as the best approach?

Dave Dellatore: We have taken what we see to be the more pragmatic approach – engage with those companies that are looking to better their environmental policies.

Much of what I think personally I’ve already said as comments to a recent Mongabay article. The Orangutan Information Centre currently works with two oil palm plantation management groups. In this case what that means is they supply funds towards our Gunung Leuser National Park (GLNP) Restoration program. Every last Indonesian rupiah they have contributed goes into this program, so it is not as if they’ve bought us out or our support. But rather that they have given funds for us to restore over 150 hectares of national park that was formerly cleared and made into palm oil plantation by two unrelated palm oil groups.

Oil palm plantation and forest in North Sumatra |

Below is an excerpt from an article we were asked to write by one of our partners, as a contribution to the RSPO newsletter. I was very surprised that our partner didn’t have an issue with what was written, as the excerpt as you can see is critical of the industry – however, since what I wrote was objective and verifiable by peer reviewed sources, there’s no arguing with it. They’re not trying to hide the fact that palm oil isn’t perfect, however, they are working with us and trying to adopt better practices.

Our GLNP Restoration program is very unique in that not only are we working within the national park, but we are engaging with all relevant stakeholders in implementation:

1. GLNP officials work closely with us in planning and implementing the replanting program. They have provided their expertise and lent their support to ensure that optimal ecosystem restoration takes place.

2. Local communities have been involved in the entire process, from planning, implementation, and eventually complete independent management and self-growth, all according to guidelines established for effective commons governance. This is extremely important as it has been shown that negative results often emerge when local people are excluded from conservation matters affecting their existence

3. We are also working with plantation management companies (unrelated to the offending agents that previously cleared the land within the protected area) interested in supporting such land rehabilitation projects.

One of the four OIC tree nurseries in the Besitang area of the Gunung Leuser National Park, North Sumatra. Courtesy of OIC |

We recognize the significant environmental impacts of the oil palm industry, with particular reference to the conversion of high conservation value forests, including orangutan habitat, to monoculture plantations. The islands of Borneo and Sumatra are the last places where orangutans exist in the wild. Over the last twenty years, more than 80% of orangutan habitat has been lost or degraded (WWF 2004). Forest cover in Sumatra alone was reduced by 61% from 1985-1997 due to logging, infrastructure development, internal migration, and plantation development (McConkey 2005), with the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) population showing a decrease of 86% over the past 100 years (Robertson and Van Schaik 2001). A United Nations report released in 2007 stated “the rapid increase in [oil palm] acreage is one of the greatest threats to orangutans and the forests on which they depend” (Nelleman et al 2007). However, we do not advocate a boycott of products containing palm oil, or companies using palm oil in their products, as this will harm the Indonesian economy, with the most impact felt by small communities dependent on these crops. Further, boycotting palm oil will only result in exporting the problem of mass deforestation to other areas such as South America. We instead call on the international community to only support companies operating oil-palm concessions that are not granted in currently forested areas, and for local retailers and consumer goods manufacturers to only source their palm oil from plantations and companies operating under international standards for sustainability such as those being developed and fostered by the RSPO.

Oil palm fresh fruit bunch. Photo by Rhet A. Butler |

We support any palm oil company with a genuine commitment to sustainable palm oil production, and it is our firm belief that through working together with more responsible companies, practices can be improved and more conservation-friendly policies formed and instituted.

There is an increasing amount of literature being published that suggests such cooperation between social/environmental NGOs and plantation companies to work together and help provide a road map of sorts for companies to operate more sustainably. This we wholeheartedly agree with, as the alternative, shunning all oil palm companies, regardless of the few trying to better their practices and work more sustainably, will result in nothing but a quicker demise for the orangutans and their forest home.

The future of the forests thus lies with 1. the governments that are granting plantation concessions on high conservation value land, 2. the companies that choose to develop this land, and 3. the worldwide consumer demand that is fueling the rapid expansion of the industry. It is therefore extremely worrying the recent news of a ruling made by the Indonesian government which opens up biodiversity AND carbon-sink rich peatland forest to plantation development (Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Nomor:14/Permentan/PL.110/2/2009). It is incompressible that in the face of solid, objective data illustrating the very high negative impacts of developing oil palm plantations on peat land and other HCVF land; the national authority has opted to allow for such development to occur.

Sumatra, 2009. |

Therefore unless the Indonesian government overturns this recent decision (something that we should all campaign for), the responsibility to do the right thing falls on the palm oil industry as well as the international consumer market. Environmental and Social NGOs will do their part in encouraging consumers to shop wisely and choose sustainable products from responsible companies. The RSPO can then function in continuing to encourage companies to pledge to work more sustainably, with the end goal being to create a brand that consumers trust and want to buy, thus shaping the way the industry as a whole operates and develops on the ground. It is important to note that not developing on forested lands does not mean a seizure of growth and profits. There are an estimated 15-20 million hectares of degraded lands in Indonesia, concentrated in Borneo and Sumatra, ready for development. It is the goal of projects such as the World Resources Institute’s POTICO (http://www.wri.org/project/potico) to steer future plantation developments onto these lands in order to put a halt to any further degradation of Indonesia’s forests for oil palm.

Again the industry is not perfect and we’re not in their pockets, but there are certain companies that are cooperating with us, trying to do the right thing and helping our conservation efforts. Of course they are still first and foremost after profits – but, so is everyone just trying to live. And if we aren’t as much, it’s because we are comfortable enough that we have the time and energy to bring up these environmental claims.

Oil palm seed. Palm oil is used widely in processed foods. By virtue of its high yield, palm oil is a cheaper substitute than other vegetable oils. In an effort to reduce costs, some candy-makers are even using palm oil in place of cocoa butter in their milk chocolate products. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

We can choose not to eat chocolate bars or whatnot, but it’s in so many products I think that we have no idea how much it is used.

Also boycotting the oil is not an answer, it won’t work as it’s in too much, and also so many peoples’ lives depend on it now that it’d be disastrous if ever a complete boycott went through. People would lose their daily livelihoods, but then thinking ahead a bit further – what would they do with all the land already covered with palm oil? In our GLNP restoration project in an area called Besitang, North Sumatra, there is still 110 hectares of palm oil trees left in the park that we are trying to get funding to get removed – and the budget we have worked out just to kill the trees so that later we can replant with indigenous trees is $16,121. So, even if the detractors who claim palm oil kills win and palm oil stops (a highly unlikely scenario, and not necessarily a desirable one), the local communities working these lands now will still need to have a livelihood. But, were palm oil to be ‘stopped’, before they could begin to earn a living in some other way, they would have to expend a massive amount of money, time, energy, petrol, etc., just to be able to clear the oil-palm planted land first, before they could use it again.

Mustaqim, head of the OIC Conservation and Forest Restoration Division, planting a tree in Sumatra. |

I think it is the only way things are going to get better – if we and other conservation bodies engage these companies and try to work towards some compromise. It’s not going to work out as best as we want it to – land is going to be lost. Palm oil (let’s not forget other plantations, such as rubber etc.) is a lucrative business, and it supports many many thousands of people who depend on it, so it’s not just going to go away or stop. But, if we are involved with the companies and can help in forming policy that is more in line with the natural environment, we can help ensure that the least amount is lost, and try for the least amount of potential damage. And, again, with these companies’ help we are undoing some of the damage done and gaining forest cover back. The alternative would be for them to ignore us, not give us anything for replanting, and not care at all about trying to work sustainably. It may sound like I’ve given up, but I haven’t – am just trying to take a realistic approach to the situation. Participating in protests, sticker campaigns and advocating immediate boycotting and the like I know must feel good and like direct action, but I don’t think it’s very productive in the end (as is evidenced by freighter ships blocked from moving for a day or two carrying on as usual, just a day or two later).

A local Besitang community member with a tree replanted in the GLNP. Photos courtesy of OIC |

What we should be using our time and energy on is yes educating people on the problems of palm oil, but then also explaining to people what they can try and do about it. The best thing for people to do on the matter is read up and review the peer-reviewed literature about oil palm so that we are all working with the same reputable facts. We’ve got to be more focused on what the actual problems are – rather than just saying ‘palm oil is bad’. In thinking about it for a minute, I think these two questions are a good exercise that makes me think about the issues more clearly: 1. Why is oil palm bad? 2. Are there better/more sustainable policies that companies could follow to lessen their damage?

The issue is never as simple as damning one company out of the hundreds out there, and at least in my understanding – is especially ineffective in Indonesia. This sort of journalism/release is very polarizing, and also it doesn’t suggest any alternatives or further information. And, similar to oil palm – how are people supposed to boycott this product/company (again – we do not advocate a boycott!)? I don’t know anyone who knows who produces the pulp that makes their paper, and am too lazy to go and see if that sort of information is on a packet of it. But even if it was there, like coffee surely you can never be totally sure where every last bean was sourced.

Mongabay: Do you have a policy on palm oil?

Dave Dellatore: The Orangutan Information Centre recognizes the significant environmental and social impacts of the oil palm industry, with particular reference to the conversion of high conservation value forests, including orangutan habitat, to monoculture plantations.

|

Healthy forest and deforested area in neighboring Borneo.

However, the OIC does not advocate a boycott of products containing palm oil, or companies using palm oil in their products. The international community must instead demand that oil-palm concessions are not granted in currently forested areas, and that local retailers and consumer goods manufacturers only source their palm oil from plantations and companies operating under international standards of oil-palm sustainability.

We support any palm oil company with a genuine commitment to sustainable palm oil production, and welcome investment in our field projects to assist companies in meeting this shared goal. It is our firm belief that through working together with such companies, practices can be improved and more conservation-friendly policies formed and instituted. The alternative, shunning all oil palm companies, regardless of the few trying to better their practices and work more sustainably, will result in nothing but a quicker demise for the orangutans and their forest home.

Mongabay: You’ve at times been vocal in responding to questionable claims made by the oil palm industry. What’s the message you are trying to convey?

Dave Dellatore: The head of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council has posted some comments on his blog which really undermine the industry’s credibility. My advice

- You would be helping the industry, your country, all of the forests and the species within, and the world so much – through simply coming out and saying that oil palm is a great, versatile, and profitable crop; and that although there are negative sides to it, namely environmental in nature, we will try and work to make it as least damaging as possible so that we too can prosper.

- Open yourself up to constructive criticism and assistance – the environmental groups are willing to compromise.

- Your stubbornness is only making the industry look foolish, what with your ridiculous comments that orangutans benefit from eating palm oil and it is good for their coats.

- I cannot speak for everyone, but for the NGO I work with we are not against development. What can be reached though is a compromise, if only you were ready to listen.

Mongabay: What are your thoughts on RSPO? What needs to be done to make it a more credible certification standard?

Dave Dellatore: RSPO is not perfect no, but it is a step in the right direction.

The blanket approach ‘palm oil is bad’ will not work, just as ‘Smoking kills’ does not. However, unlike smoking which has its addictive properties, palm oil does not carry those same properties and the industry is not marketing a product that clearly is deadly. The industry can be shifted to become more sustainable. But for that to happen we have to provide a roadmap of sorts and pull them along the right way. Coming out guns blazing or whatever will just put them on the defensive (if they even feel it at all – think about how far away the stores in the west are both physically and also market wise from the plantations) and to label all environmental groups as tree huggers, which is very easy for people to shrug off and not take seriously.

ORANGUTANS

Mongabay: How is nature tourism affecting orangutans?

Mother orangutan and baby at Bukit Lawang. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Dave Dellatore: Ecotourism should not be confused with wildlife or nature tourism, which is based solely on interactions with wildlife such as viewing/photographing, direct contact and feeding. True ecotourism has the potential to contribute both to Sumatran orangutan conservation as well as development goals through its self-generating administrative revenue, and can thus be posited as a sustainable livelihood opportunity that local communities living near protected areas can embrace. However, it must be managed responsibly in order to be a sustainable enterprise.

Although popular sites, such as Bukit Lawang, is currently known as an orangutan viewing centre, Sumatran orangutans are still a critically endangered species living within the confines of the Gunung Leuser National Park, part of the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Video footage of mother orangutan cannibalizing her dead offspring. Video taken by Dellatore and shown on BBC. |

Although it is forbidden to touch, feed, or disturb the orangutans, such practices still do occur for the enjoyment of visitors. Large groups of visitors in Bukit Lawang are often brought within close proximity to, and in actual physical contact with the orangutans. This is a major cause for concern in terms of both zoonotic and also anthropozoonotic disease transfer due to the close phylogenetic relationship between humans and orangutans. Accompanying this is unauthorized food provisioning, which in addition to potential disease transfer also serves to discourage the semi-wild population from reducing any dependence on humans and becoming free-living in the wild. Through some research conducted in the past I’ve also encountered aberrant behaviors never before seen in any other great ape population – mother orangutans cannibalizing the remains of their own dead infants. Although we can’t say definitively that ‘x happened because of y’, it can certainly be argued (the arguments are laid out in the journal article in Primates ) that with the illegal feedings and interactions that take place in BL, and that such behavior never before being seen in 40+ years of orangutan research – that this is certainly not normal and that it would be best to reduce as much as possible any stressors and/or artificial relationships and interactions with these apes. It’s not to say that tourism is bad and should be stopped – but that it has to be conducted responsibly.

With so few free-ranging populations remaining, every number counts and must be protected. It is completely unsustainable for the tourism industry in Bukit Lawang to continue to allow practices which significantly alter the behavior, and potentially threaten the health, of these orangutans. There is no reason that tourism in Bukit Lawang cannot be made sustainable, as it does not necessarily carry any of the five main limits of ecotourism: lack of infrastructure, difficulties in access, political instability, ineffective marketing, or an absence of flagship species (Wells, 1992). What then must happen is an overhaul of the tourism system in place, and what is most needed is a major education program targeting local people, forest guides and tourist visitors.

Gunung Leuser National Park. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

For these reasons the OIC has been running the Sumatran Orangutan Ecotourism Development program in BL (which with support from UNESCO was also expanded to include the nearby tourism site of Tangkahan, most well-known for its ex-captive elephant trekking) in late 2008. With this we have implemented measures to intervene and raise tourism standards, including setting new visitation guidelines that best protect the orangutans and other wildlife, as well as the local community and visitors.

Effective guiding creates more support for conservation efforts and results in less support for practices which are detrimental to the forests and orangutan conservation, such as using unsustainable, ‘non-certified’ timber products. Further, on a more indirect level, once government partners see the benefits of a financially-rewarding, high conservation value, low-impact program, they could then replicate these practices in other areas hosting tourism programs.

Mongabay: What are some of the challenges facing orangutan rehabilitation programs?

Dave Dellatore: A big challenge is securing a suitable release environment in which rehabilitated animals may survive and reproduce. There is simply not much viable forest left, especially in Sumatra which is much smaller compared to Kalimantan, so that finding a suitable region is more difficult and complicated. Further, even if a site is located and secured, it is not just a matter of releasing a random population of orangutans there, as the success of reintroduction depends a large part on the suitability of the release site and the ability of the animals to establish a viable breeding population (Woodford and Rossiter, 1994; Cheyne, 2006). Within that there are many factors to consider, such as:

Disease transmission risk

Reintroduction of a species from an outside area must not be conducted haphazardly, as “each animal is not simply a representative of a single species but rather a biological package containing a selection of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, helminthes and arthropods” (Nettles, 1988). Therefore a reintroduction program must be extremely careful not to jeopardize the habitat and all its original inhabitants (May, 1991; Yeager and Silver, 1999). Ex-captives are particularly susceptible to infectious disease (Woodford and Rossiter, 1994; Daszak, 2000) as they pass through care center settings that are often overcrowded, which greatly increases their chances of contracting disease. Great ape reintroduction programs require additional concern as the apes are phylogenetically close to humans and thus susceptible to human infectious diseases (Woodford et al., 2002).

Mother orangutan and baby at Bukit Lawang. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Ex-captive populations of primates may be at an additional risk of contracting disease, due to behavioral traits learned in captivity. For example, under natural conditions, orangutans are semi-solitary and rarely congregate in groups (Rodman, 1988). Ex-captives, due to their altered upbringing, may be more social once returned to the wild (Yeager, 1997). With parasite host behavior shown to correlate with exposure to parasites (Hart, 1990; Moore, 2002; Ezenwa, 2004), these individuals, operating at a higher than normal population density have a greater chance of disease transmission. In addition the reintroduced population may be subjected to diseases and parasites that are local in distribution so that new arrivals without local ecological adaptations may quickly succumb to illness (Woodford and Rossiter, 1994; Cunningham, 1996). Habitat degradation has been linked to improved conditions for disease vectors (Woodford et al., 2002; Chapman et al., 2005; Gillespie and Chapman, 2006), so that particular care should be taken in secondary forest. Therefore particular care should be taken in post-release monitoring of individuals and the environment for any potential increased infection threats.

Post release monitoring can assist in detecting disease problems of released individuals and therein provide an early warning system of infection problems that might affect the population (Woodford and Rossiter, 1994). Unfortunately, although the IUCN lists long term post-release monitoring as one of the most important facets of a reintroduction program (Beck et al., 2007), many primate release sites are reported to have poor post-release monitoring records (Aveling and Mitchell, 1982; Woodford and Rossiter, 1994; Sarrazin and Barbault, 1996; Yeager, 1997; Cowlishaw and Dunbar, 2000; Kleiman et al., 2000; Breitenmoser et al., 2001; Goossens et al., 2002). This is I think starting to improve, but there is still surprisingly little published data available on orangutan reintroductions. So we are missing out on the opportunity to learn what has worked and hasn’t worked for different sites – forcing everyone to conduct the same trial and error system over and over.

Risks associated with genetics

Orangutan conservation information materials distributed to children during a community visit in North Sumatra. Photo courtesy of OIC. |

Reintroduction programs have been shown to give genetic considerations low practical priority (Goossens et al., 2002), with short term factors of greater concern than genetic processes which act on a longer time scale (Caro and Laurenson, 1994). As loss of genetic variability can be a major threat to the survival of a population, it is important to consider the genetic characteristics of the animals to be reintroduced. By studying the molecular characteristics of the population, one can develop strategies to offset the genetic threats faced by small populations (Lande and Barrowclough, 1987; Vasarhelyi and Martin, 1994; Sutherland, 1998). Selection of animals for reintroduction should be based on genetic and demographic considerations, so as to ensure that the founder population is as representative as possible of the gene pool available in captivity (Foose, 1991; Beck et al., 1994). The founder population must also be viable – large enough and with enough genetic variability so as to provide a level of protection against the stochastic problems of the environment (Foose, 1991; May, 1991; Kalinowski and Waples, 2002).

Care must be taken in reintroducing individuals into an area with a remnant wild population (something that current Indonesian law stipulates should not occur with orangutan releases – however, it has and I think does still happen), as it could result in hybridization and the ‘contamination’ of any local adaptations (Foose, 1991; Madsen et al., 1999; Goossens et al., 2002). Further, there is enough geographic variation in the genetic make up of Bornean orangutans – there are now four recognized subpopulations (Warren et al., 2001); so care must be taken to maintain genetic integrity across the island so as to avoid releasing subspecies from other outside areas and hybridization.

Social situation / politics

Children visited as part of an OIC mobile library visit to Ketambe, Southeast Aceh. Photo courtesy of OIC. |

Related to the section below on social/outreach – for reintroduction it is equally important to create a safe political environment as it is a physical environment. If a program is implemented from above with no care or attention given to the local community surrounding it, the project is likely doomed to fail.

In addition to these factors, there are many more to consider, such as habitat viability, carrying capacity, behavioral adaptation, etc. Of course all of this takes time and money to carry out – with neither being available in any great surplus in today’s conservation climate.

Mongabay: Orangutan rehabilitation centers are helping save a lot of orangutans, but the number of orphans seems to only be increasing. Thus rehabilitation doesn’t seem to be sustainable in the long-run. What’s the ultimate solution?

Dave Dellatore: Rehabilitation and reintroduction were never intended to be a stand alone solution, but are rather reactions to the greater problem of shrinking habitat and displacement of individuals from the forest therein. It’s an example of treating the symptom rather than the cause. For orangutans it actually started in the 1960s when it was thought that the orangutan was nearly extinct in the wild, with an estimated number of 5,000 (Harrison, 1962, cited in Singleton and Aprianto, 2001). It was intended for the purposes of fighting the illegal pet trade as well as to reinforce the free ranging populations living in the wild (Rijksen and Meijaard, 1999).

This doesn’t mean that it doesn’t work, or that it isn’t a useful conservation measure, as ex-captive orangutans are still members of the same endangered and critically endangered species – so that if released properly they can bolster populations in the wild.

Male orangutan in GNLP. Photo by Rhet A. Butler |

I would disagree with the blanket statement that rehabilitation and reintroduction is not part of conservation. That always tends to come out with people saying that it’s just a distraction/diversion from conserving forest and orangutans still in the wild – yes, that needs to be done. But in the meantime we have to do something with the thousand plus and growing (not sure the current figures) already in the ‘system’. People seem to have a different view (Indonesian government has a decree against it – but that isn’t always followed) of whether it’s permissible to release ex-captives into an area that already has a wild population – but the way I see it if there is ample forest left in an area and all the appropriate health checks are carried out and post-release monitoring carried out it really could help wild populations and increase genetic diversity (not to mention bolstering numbers of endangered and critically endangered orangutans – which they still are whether or not they were once held in captivity).

The ‘ultimate solution’ necessarily differs from the ‘ideal’ solution. The ideal solution being a secured, protected stretch of forest, free from encroachment and with a sizable buffer zone surrounding it; all of which simply isn’t going to happen.

Oil palm nursery. Photo by Rhet A. Butler |

I am not sure an ultimate solution exists, but regardless, any solution is going to require an expanse of forest that is protected from land clearing and degradation. However, the size of these theoretical lands, may also be much less than the ‘ideal’. As the last remaining great forest tracts are exhausted, the priority effort (Mackinnon and Mackinnon, 1991; Yeager, 1997; Rosen et al., 2001) to preserve large undisturbed wild populations of orangutans may come to an end, leaving only managed populations to survive in fragments and reserves (Russon, 2002; Cheyne, 2006; UNEP, 2007). This new approach will require a smaller area of conservation focus and therefore a greater emphasis on individual behaviour and fitness (Anthony and Blumstein, 2000). In my opinion then relatively small populations of reintroduced orangutans could thus be put forward as the basis for forming such landscapes and in the process result in more protected forests and better chances for survival of the species (Mackinnon and Mackinnon, 1991).

Mongabay: Do you have examples of sites in Sumatra where orangutans have been reintroduced only to have the forest be subsequently cleared?

Dave Dellatore: I don’t know of any examples of this, which I think perhaps relates to many reintroduction programs being overly cautious in waiting for there to be a safe, secured release site. Of which of course there is not much open habitat left that is suitable for releasing ex-captive orangutans, because there is either a wild population already present (current Indonesian law dictates that releases not take place where there are still wild orangutans, so as to avoid any potential disease transmission, overcrowding, and also behavioral changes), the land is not large enough or bearing enough food to support a viable population of orangutans, or the land is either not secure from encroachment.

Mongabay: What is the role of education and outreach in protecting orangutans?

Dave Dellatore: Educating local communities on the importance of forest conservation is essential to develop their capacity to sustainably manage their environment. Through our work we use the orangutan as our flagship species of focus, and highlight that in addition to their intrinsic value, orangutans and their rainforest homes provide highly valuable ecological services that we all benefit from everyday, and that to lose them would be disastrous.

Orangutan conservation information materials distributed to children during a community visit in North Sumatra.

Children visiting the inside of the OIC Orang-U-Van mobile library, as part of the Plantation Roadshows Program |

Often in conservation complete focus is given to the species/habitat of concern, with no regard to the social environment it is within. Yet with human population on the rise with no clear end in sight, more land is going to be converted for human use. Many local people in habitat countries view wildlife conservation as misguided as the needs of wildlife have taken precedence over that of themselves (Hackel, 1999). It is not therefore surprising that in these situations conservation efforts have not been very successful. The future of wildlife thus depends on the ability of the local people in habitat countries to prioritize conservation (May, 1991; Wright, 1992; Strier, 2007).

Though many people in the west may regard primates with any number of endearments and campaign for their protection, to many people ‘co-habitating’ with them they carry no special distinction. With many primate habitat countries considered developing nations, foreign conservationists are inherently on sensitive ground. Oftentimes it would be more profitable for the people of developing nations to clear fell and sell the forests (ITTO, 2005) and invest in development than to conserve the land. Thus to have relatively rich foreign conservationists demand that local people in other countries not follow suit and develop their own land and enjoy the benefits inherent is a form of ‘forced primitivism’ (Goodland, 1982). A balance must be struck that meets the needs of the local people while still allowing for conservation programs such as reintroduction to succeed. As development projects are now widely expected to consider the environmental consequences of their actions, so are conservation agencies equally expected to consider theirs on the people around the conservation target (Sutherland, 2000).

Thus the education programs carried out by the OIC stimulate long-lasting effects at a grass-roots level, changing the way people see their environment and inspiring them to become actively involved in conservation activities. Previous studies have shown that changes in attitude can have a positive impact on conservation (Biodiversity Conservation Network, 1999). Thus when people are taught about the many intrinsic ecological services and values provided by rainforest ecosystems, as well as shown the ways in which they themselves can make changes in their lives that can help protect the environment, they are much more likely to support and campaign for conservation (Eltringham 1994; Rijksen and Meijaard 1999, van Beukering et al. 2003).

Q&A WITH PANUT HADISISWOYO

Mongabay: Have you seen a change in the driver of orangutan rescues since you started working in orangutan conservation?

Panut Hadisiswoyo, Founding Director of the OIC, in the forest of Bukit Lawang |

Panut Hadisiswoyo: Yes, I have seen more people become more aware about the plight of orangutan and thus I have seen more orangutans being rescued or handed over from illegal keeping to rescue center, although it implies that the illegal orangutan keeping and trade seems to be still occurring, with the number of orangutan confiscated in northern Sumatra increasing every year. Nevertheless, because the number of campaign actions by various conservation groups to promote the orangutan conservation have significantly increased over the last five years, the increase in orangutan confiscation and hand over from community members may have happened as a result of these intensive campaign activities which highlight laws for the protection of orangutan. The most significant indicator for the change in the driver of orangutan rescue as far as I am concerned is that enforcement of laws protecting orangutans have become more apparent and effective in the field. The local forestry department, despite less enthusiastic commitment, has put efforts to collaborate with key orangutan conservation NGOs in Sumatra such as SOCP and OIC to eradicate illegal orangutan keeping and trade in the region.

Mongabay: What lead you to take an interest in orangutans?

OIC staff member Cali hosting opening an OIC Orang-U-Van school visit in Berastagi, North Sumatra. Photo courtesy of OIC. |

Panut Hadisiswoyo: Orangutans amazed and fascinated me. The first time I explored Gunung Leuser forest in South Aceh back in 1998, I saw a juvenile female orangutan approaching our research station with no fear at all. I was curious why this orangutan looked quite habituated, or comfortable in the presence of humans, in a forest area that is far from human settlement. In fact, I soon realized that research activities may have impacted the behavior of orangutans because some research assistant sometimes encouraged orangutans to come closer by offering them food. Since then, my curiosity has led me to actively learn more about orangutans. The more I learned, the less I felt I knew about orangutans. There was always something new about orangutans I learned through various research and studies conducted by scientists, who are mainly westerners. This inspired me to become involved in orangutan research. However, with current dramatic decline in the orangutan population in Sumatra due to habitat loss and illegal poaching, I become more pragmatic and worked to pioneer practical actions that can directly help conserve orangutans and their habitat.

Mongabay: How did you first start working with orangutans?

Panut Hadisiswoyo: I started working with orangutans when I founded the Orangutan Information Centre (OIC) in 2003. Since the inception of OIC, my life has been devoted only to orangutans and OIC.

mongabay: What are the biggest conservation issues in Gunung Leuser National Park? Are park boundaries well respected?

Panut Hadisiswoyo: The biggest conservation issue in Gunung Leuser National Park is illegal encroachment in the park area for agricultural development and illegal settlement. Park boundaries are mainly respected in ecotourism areas such as in Bukit Lawang and Tangkahan where park rangers generally work intensively to monitor the park areas. Also, local people living near ecotourism area in Gunung Leuser know better the boundary of park, but those who live far from ecotourism site mainly do not know the boundary. A survey recently conducted by the OIC team in Halaban village, which is adjacent to GLNP area in Besitang, Langkat, revealed that almost 80 per cent of respondents did not know the boundary of Gunung Leuser and thus many of them trespassed the park without knowing the existence of national park.

Q&A WITH HELEN BUCKLAND

Mongabay: What happened at the last RSPO meeting?

Helen Buckland:

Helen Buckland |

The 6th annual meeting and 5th General Assembly of the RSPO took place from 18th-20th November 2008 in Nusa Dua, Bali, Indonesia. Over 500 delegates from 27 countries were in attendance, and participants included representatives from plantation management groups, consumer goods manufacturers, retailers, and environmental and social NGOs. The NGO presence included delegates from WWF, Conservation International, PanEco Foundation, Wetlands International, Fauna and Flora International, Greenpeace, Oxfam International, Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, Sumatran Orangutan Society, SawitWatch, Eye on Aceh, and the Forest Peoples Programme.

The film shown at the start of the conference drew attention to the use of fire for land clearance, and the social and environmental impacts of the industry, including displacement of indigenous communities and the destruction of orangutan habitat. This set the general tone of the meeting – compared to previous years, there was much more frequent reference to, and acknowledgment of, these problems, although of course not from all individuals. In his opening speech, Jan Kees Vis, President of the RSPO and Head of Sustainable Agriculture for Unilever, stated that all three pillars of sustainability are in crisis – people, planet and profit. He held up RSPO as proof that it is possible to find sustainable solutions, but also acknowledged that “some think it is too little, too late.”

The “Green Answer” or Greenwashing?

Britain’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), a group that regulates advertisements, banned the above advertisment [PDF] from the palm oil industry. ASA ruled that a campaign run by the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) makes dubious claims. |

The secretary general of the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture made a speech to officially open the conference. In a rather inflammatory address, he referred to claims about Indonesia’s CO2 emissions from deforestation as outrageous accusations. He rejected a moratorium on deforestation, saying that Indonesia has its own program to protect 60% of forests, but did not give any more details. The Indonesian government departments of forestry and environment are apparently working together to assess regulations regarding the use of peatlands for agriculture. He stated that 6.2 million hectares of oil palms have been planted in Indonesia, covering only around 5% of the country’s total land area. These figures were used as “evidence” that the palm oil industry is not a primary driver for deforestation, but data from SawitWatch, an Indonesian NGO working to protect the rights of indigenous people, estimates that a further 18 million hectares have been cleared for new plantations . The speech seemed at odds with the tone of the RSPO President’s address, and did not inspire optimism that the Indonesian government acknowledges the rationale behind the existence of the RSPO – the need to fundamentally change the way the palm oil industry operates.

Mongabay: How is certification progressing?

Helen Buckland:

In 2008 three palm oil companies (all Malaysian owned) were the first to be officially certified by the RSPO (United Plantations, Sime Darby and New Britain Palm Oil), and several others are currently going through the audit process. As of the beginning of 2009, Musim Mas became the first Indonesian palm oil plantation management group to become certified. The first shipment of CSPO was, at the time of the conference, on its way to Rotterdam, The Netherlands, from United Plantations.

Oil palm plantation in North Sumatra in May 2009 |

Currently, an Audit Review Panel examines every audit before a company becomes officially certified. However this has become a serious bottleneck in the certification process, because the panel is being very cautious and as thorough as possible in making these assessments. Musim Mas, for example, submitted their paperwork to be certified several months before the certification was granted. The current system was described as “untenable” in the future, but no alternative suggestions were made. It was acknowledged that the approval of RSPO-endorsed certification bodies needs to be outsourced in order to remain independent and neutral, as in FSC/MSC (Forestry Stewardship Council / Marine Stewardship Council) schemes.

Greenpeace has called into question the validity of the audit carried out on United Plantations’ holdings in Malaysia on several grounds , and there is an informal dispute resolution process in progress. Complaints can only be made through the RSPO grievance procedure AFTER certification has been granted. This seems counter-intuitive, as it would be publicly embarrassing for the RSPO to have to revoke RSPO certified status from a company. A more logical system would make audit reports publicly available through the RSPO website for a specified period, so that any complaints or objections could be made before the company is officially certified. This would allow groups to come forward with evidence that a company has breached any of the Principles & Criteria.

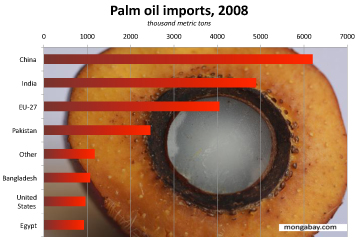

Oil palm plantation and logged-over forest in Borneo. |

There were also presentations from representatives of Japanese, Chinese and Indian palm oil companies. However, in the subsequent question and answer session, when the panel was asked to quantify the demand for CSPO in China and India (the largest importers of palm oil alongside Europe), there was an admission that there is currently zero demand for this product! This was linked to the fact that there have been no NGO campaigns in these countries, therefore consumers have very little information to differentiate standard palm oil from CSPO – they don’t know about the problems with the current industry model, or why the RSPO exists, and therefore there is very little appreciation of the value of CSPO. It seems that whilst NGOs are condemned for drawing attention to the social and environmental problems associated with the industry, there is also an expectation that these groups should communicate positive messages about the value of the RSPO and, in particular CSPO, to potential consumers.

Regarding the poor demand for the CSPO which is now available on the market, that could be due to low confidence in the palm oil actually being from sustainable sources (for example due to reports by groups such as Greenpeace showing holes in the certification process), or it could be that the retailers and consumer goods manufacturers are simply not meeting their commitments to buy CSPO, possibly due to the price premium, or other reasons. Following a campaign in the UK in 2005, all major retailers and several consumer goods manufacturers joined the RSPO and made a public commitment to purchasing CSPO when it became available. Now, several years later, many more companies around the world have also joined, and a small volume of CSPO is now available, but a tiny percentage has been bought – perhaps we need to put more pressure on these companies to meet their commitments and genuinely support the push for sustainability in the palm oil industry, rather than just making empty promises.

Mongabay: Was there much discussion at the meeting of marketing the RSPO brand?

Helen Buckland:

Chart/Graph: Top palm oil importers for the 2008 market year. Click image to enlarge. Chart by Rhett A. Butler. |

There was discussion about the need for aggressive marketing of the RSPO brand, and frequent acknowledgement of the need to prove the system as being credible. Palm oil is often a hidden ingredient, listed simply as “vegetable oil” or one of its many derivatives on product packaging, so many manufacturers may have no interest in having a CSPO logo on their packaging. Such a logo would inform consumers that palm oil in the product has been sourced from RSPO-certified plantations, offering (in theory) some assurance that no human rights abuses or environmental destruction has taken place. Some companies, such as Cadbury Schweppes, have publicly rejected the idea of an on-product logo, but suggest advertising the use of CSPO through their websites and annual Corporate Social Responsibility reports. The RSPO executive board has also decided against an official logo. Some companies may use their own unofficial logo to make claims about the source of the palm oil in their products, but this opens the system up to reduced credibility. An RSPO-endorsed logo would be highly beneficial in terms of communication with consumers, and adding value to products containing CSPO.

Mongabay: Were other challenges discussed?

Helen Buckland:

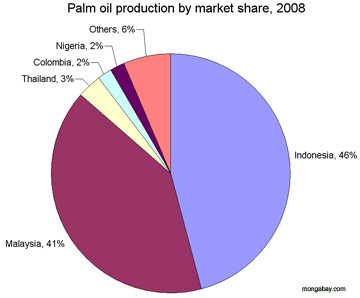

Chart/Graph: Market share of top 5 palm oil producers for the 2008 market year. Chart by Rhett A. Butler. |

A presentation was given by Dr Thomas Fairhurst from WWF international on the need to encourage the development and use of higher yielding varieties of oil palm, and to implement better management practices at the plantation level, so that growth in production can be achieved to meet growing global demand without a concurrent increase in forest land conversion. Palm oil production has increased exponentially over the last 30 years, but this has been driven entirely by area expansion, and yields have not been increasing. There is currently a significant gap between actual and potential yields on existing plantations, and it is theoretically possible to meet growth in demand, without jeopardising forests and peatlands, through yield intensification and expansion onto degraded land. Research is currently underway into the agronomics and economics of plantation development on degraded land. The production of a landscape level land suitability map to identify appropriate areas for expansion would be an extremely useful tool in liasing with local governments in Indonesia and elsewhere to redirect future plantation development onto non-HCVF land (High Conservation Value Forest). It seems that at least some members of the palm oil industry are aware that “the world is watching”, and that conversion of HCVF cannot continue unchallenged.

Smallholders are still not adequately accounted for in terms of assistance in understanding and meeting the P&Cs. There appears to have been very minimal progress in this area. Smallholders are hesitant to commit to the P&C due to the significant costs involved, but the Malaysian government has pledged RM50million (approximately 14 million USD) in 2009 to assist smallholders to achieve RSPO certification. However, there have been no contributions or similar schemes from the Indonesian government. Several smallholders attended the conference, but were only able to voice their concerns during question and answer sessions at the end of each session, having been denied the opportunity to make a presentation to the entire conference.

Mongabay: There were some interesting resolutions proposed for the meeting. What was the outcome of these?

Helen Buckland:

Wetlands International, an international environmental NGO, called for a moratorium on the deforestation of peatlands. This resolution was not passed, but the circumstances for this were based on a technicality in the voting procedure rather than an outright rejection of the proposal. Wetlands International asked for the resolution to be handled by the RSPO Executive Board . Jan Kees Vis (president of RSPO and Director of Sustainable Agriculture at Unilever) was clearly in favour of the moratorium, but no official position from the RSPO has been reached on this yet. Even if this resolution/moratorium is passed, it is still only an obligation for RSPO members, which makes up only around 40% of the global palm oil industry.

Plantation in North Sumatra. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

WWF put forward a proposal that RSPO members should provide advance notification of plans to establish new plantation areas. It was suggested that land-use plans, including HCV assessments, be verified by a third party and then published on the RSPO website for 30 days for public review. This turned out to be highly controversial, resulting in a temporary walk-out from the General Assembly by several members, mostly representing Indonesian palm oil growers, and led by the Executive Chairman of the Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI). This resolution would have made it far more difficult for plantation management groups to have a small number of flagship plantations certified whilst continuing with “business as usual” and opening up HCVF areas for new plantation developments. In general it seems the Indonesian growers do not yet see sufficient reason to fully embrace the tenets of sustainability and RSPO. In the spirit of compromise, the resolution was changed, and the GA instead voted to accept a resolution to form a working group tasked with developing a credible and transparent “procedure to assure compliance with RSPO Principles and Criteria concerning new plantings.”

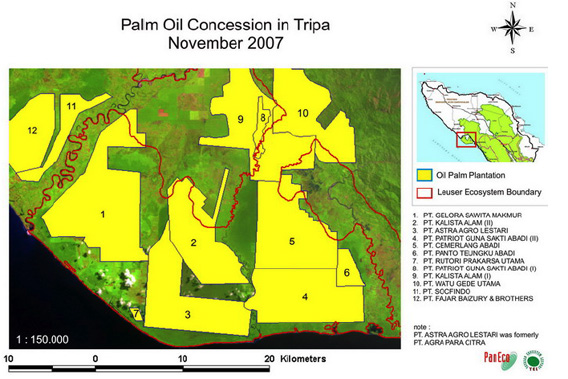

PanEco, a Swiss organization, made a presentation about the Tripa peatland swaps, which are being cleared for oil palm cultivation by a company that is not a member of the RSPO. The Tripa area is in the Aceh province of northwest Sumatra is home to one of just six remaining viable populations of the critically endangered Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii). The forest covers around 60,000 ha and provides “crucial environmental services both locally, and globally” . The Tripa peat swamps sequester millions of metric tons of carbon, which is being released into the atmosphere as it is converted to oil palm plantations. The PanEco resolution to “urgently request the RSPO to take action to stop the destruction of Tripa peat swamp forests” and “request the RSPO to adhere to the credibility of its role and drastically improve its efficiency by implementing an effective mechanism to control bad practices of the palm oil industry”– narrowly passed (38 for, 30 against, 61 abstained). There was mixed response, with one palm oil grower expressing disbelief that the RSPO was being asked to intervene in the situation as the ‘culprits’ are not members, and therefore outside RSPO jurisdiction. Despite this, a resolution was passed that the RSPO would support efforts to stop clearance in this area. This resolution targets P.T. Astra Agro Lestari that holds a concession covering the largest remaining tracts of forest in Tripa, that should in fact have been protected by many Indonesian policies and laws. P.T. Astra Agro Lestari has business ties with key RSPO members from all sectors, and is owned by UK company Jardines.

Images showing oil palm plantation concessions and forest cover change from 1990 to 2005 in Tripa. Courtesy of YEL/PanEco Foundation |

Greenpeace had put pressure on Unilever to develop a resolution calling for a moratorium on logging in HCVF areas, which was due to be voted on. However, the resolution was removed from the schedule with no explanation.

Mongabay: What were your overall thoughts on the meeting?

Helen Buckland:

The theme of the conference last year was “The Gathering Momentum”, and I think that this was fairly apt. Having attended four RSPO conferences and observed the process for several years, it has been slow to start to actually move towards achieving its objectives, but I do believe that progress has been made since the last Roundtable meeting a year ago. Nine certification bodies have been approved by the RSPO in the last year to be able to assess the performance of plantations against the P&Cs, and the first shipment of “CSPO” is on its way to Europe. However, questions have been raised by Greenpeace about this shipment, and many observers, including Friends of the Earth Indonesia (WALHI) and the Rainforest Action Network, have argued that there are fundamental flaws in the whole certification system, condemning the RSPO as being inadequate and ineffectual.

Oil palm nursery in North Sumatra.

|

In the RSPO’s own press release following the conference, it was stated that “One of the main topics discussed was the involvement of Governments.” Having attended the conference, I find that statement highly misleading. It was disappointing that discussions on government involvement were sidelined to a world café session which was attended by just a handful of people, as the lack of government engagement is a crucial limiting factor to the whole RSPO process. Governmental take-up of the RSPO P&C into land-use planning policy is essential in order to reduce the environmental and social impacts of the expanding industry, but there is no evidence that this is on the horizon.

Palm oil producing members are required to work towards the implementation of the P&Cs and towards certification of plantation estates. Principle 8 of the RSPO P & Cs calls for a commitment to continuous improvement in a company’s operations. To this end, members are required to make annual reports on their progress towards meeting the Principles and Criteria. In a private discussion with a member of the RSPO Executive Board, compliance with this requirement was described as “embarrassingly low.” However, breaching this obligation carries no consequences whatsoever. Many companies, organizations and consumers now assume that RSPO membership implies the production or sourcing of sustainable palm oil, which is simply not the case in practice. A crucial weakness of the RSPO is that membership is effectively meaningless. Membership of the RSPO implies nothing about a company’s actual practices on the ground, and any company or organization can buy membership for 2,000 Euro per year. It is apparent that many companies are not yet ready to meet their commitments as members of the RSPO and actually enforce the P&Cs on the ground. There is a strong concern that some companies will have “flagship” plantations certified, whilst carrying on with “business as usual” in the majority of their holdings.

The RSPO is primarily concerned with being able to sell a “sustainable” commodity at a premium. There are many flaws inherent in the system, and there is currently no guarantee that palm oil sold as CSPO actually comes from a plantation that has not caused the destruction of HCV forests, or that companies certified as “sustainable” are operating to the same standard on all of their plantation estates. The credibility of the RSPO certification system is unproven, and the RSPO Principles and Criteria are very much still a work in progress, which was acknowledged publicly in the conference.

Recent clearing on the border of GLNP in North Sumatra.  Rainforest in GNLP. Photos by Rhett A. Butler. |

The palm oil industry WILL continue to expand. What we need to be concerned with is HOW this expansion will happen – at the expense of HCVF, or onto the millions of hectares of unused grasslands available for cultivation (excluding those areas of significance to local communities). Project POTICO (Palm Oil, Timber and Carbon Offsets), a new initiative launched by the World Resources Institute (WRI), aims to use investment in sustainable palm oil, FSC-certified timber, and carbon offsets to divert new oil palm plantations onto degraded lands and bring forests that were slated for conversion into certified sustainable forestry. If successful, the project will demonstrate the business case for developing new plantations on degraded land. Currently palm oil companies often rely on the sale of timber that is cleared when preparing the plantation to provide an interim income until the new plantation becomes profitable, usually after 4 years of operation. This new model has the potential to relieve pressure on HCV forests, curb illegal logging, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, conserve biodiversity, and enhance sustainable livelihoods of local people.

A significant challenge is that 60% of palm oil is produced by companies which are not members of the RSPO. Unsustainable practices by ANY palm oil producer, whether an RSPO member or not, reflects badly on the entire industry. This is seemingly understood by a minority of RSPO member companies, and the rest use their membership status to shield themselves from criticism.

Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

It is apparent that many members are not pursuing certification, but are waiting until the benefits of doing so have been proven by other companies. The RSPO is a voluntary initiative and will never have the power to put stringent measures in place to stop deforestation in Indonesia or elsewhere. The responsibility for this lies with the governments that are granting plantation concessions on high conservation value land, with the companies that choose to develop this land, and with the worldwide consumer market that is fueling the rapid expansion of the industry. The RSPO is encouraging companies to pledge to work more sustainably, with the end goal to create a brand that consumers trust and want to buy, thus shaping the way the industry as a whole operates and develops on the ground. This will take more time, and may never be enough. It is the actions of companies outside the RSPO, and the attitudes of some members, which are causing low confidence in the ability of the body to deliver any real change. The RSPO is a step in the right direction, but detractors are damaging confidence in the market, affecting demand for CSPO, and thereby limiting the progress and ability of the RSPO to push the industry towards sustainability.

Debate about the effectiveness of the RSPO may actually be distracting organizations from the bigger picture and the fact that the majority of the world’s palm oil companies are not RSPO members, have made no commitment to sustainable practices, and are continuing to open forest areas for cultivation. Concerned parties and organizations should be focusing attention on governments rather than voluntary corporate responsibility in order to influence land-use policies.

CITATIONS

- Ancrenaz M., Dabek L., and O’Neil, S. (2007). The costs of exclusion: Recognizing a role for local communities in biodiversity conservation. PloS Biol 5(11).

- Anthony, L. L. and Blumstein, D. T. (2000). Integrating Behaviour into Wildlife Conservation:

- Beck, B. B., Rapaport, L. G., Stanley Price, M. R. and Wilson, A. C. (1994). Reintroduction of Captive-Born Animals. In: Olney, P. J. S., Mace, G.M. & Feistner, A.T.C. (ed.) Creative Conservation: Interactive Management of Wild and Captive Animals. London: Chapman & Hall, pp.265–286.

- Beck, B., Walkup, K., Rodrigues, M., Unwin, S., Travis, D, Stoinski, T. (2007) Best Practice Guidelines for the Re-introduction of Great Apes. Gland, Switzerland, SSC Primate Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union.

- Bhagwat, S.A., Willis, K.J. (2008). Agroforestry as a Solution to the Oil-Palm Debate. Conservation Biology 22(6), pp. 1368-1369

- Biodiversity Conservation Network (1999). Final Stories from the Field. Biodiversity Support

- Breitenmoser, U., Breitenmoser-Wüsten, C., Carbyn, L. N. and Funk, S. M. (2001). Assessment of Carnivore Reintroductions. In: Gittleman, J. L., Funk, S. M., Wayne, R. K. and Macdonald, D. W. (eds.) Carnivore Conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.241-281.

- Chapman, C. A., Gillespie, T. R. and Goldberg, T. L. (2005). Primates and the Ecology of Their Infectious Diseases: How Will Anthropogenic Change Affect Host-Parasite Interactions? EVOLUTIONARY ANTHROPOLOGY 14 (4), pp.134-144.

- Cheyne, S. M. (2006). Wildlife Reintroduction: Considerations of Habitat Quality at the Release Site. BMC ECOLOGY 6 (1), pp.1-8.

- Colchester M, Jiwan N, Andiko , Sirait MT, Firdaus AY, Surambo A and Pane H. 2006. Tanah Yang Dijanjikan: Minyak Sawit dan Pembebasan Tanah di Indonesia – Implikasi Terhadap Masyarakat Lokal dan Masyarakat Adat. Bogor, Indonesia. Forest People Programme (FPP), Sawit Watch, HUMA, World Agroforestry Centre – ICRAF, SEA Regional Office.

- Cowlishaw, G. and Dunbar, R. (2000). Primate Conservation Biology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cunningham, A. A. (1996). Disease Risks of Wildlife Translocations. CONSERVATION BIOLOGY 10 (2), pp.349-353.

- Danielsen, F., Beukema, H., Burgess, N.D., Parish, F., Brühl, C.A., Donald, P.F., Murdiyarso, D, Phalan, B., Reijnders, L. Struebig, M., Fitzherbert, E.B. (2008). Biofuel Plantations on Forested Lands: Double Jeopardy for Biodiversity and Climate. Conservation Biology.

- Daszak, P. (2000). Emerging Infectious Diseases of Wildlife– Threats to Biodiversity and Human Health. Science 287 (5452), pp.443-449.

- Dellatore, D.F., Waitt, C.D., Foitova, I., Two cases of mother-infant cannibalism in orangutans. Primates, 2009. 50(3), pp. 277-81. DOI 10.1007/s10329-009-0142-5.

- Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., Stern, P. (2003). The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 302, pp. 1907-1912.

- Eltringham, S. K. (1994). Can Wildlife Pay Its Way? Oryx 28 (3), pp.163-168.

- Ezenwa, V. O. (2004). Host Social Behavior and Parasitic Infection: A Multifactorial Approach. Behavioral Ecology 15 (3), pp.446-454.

- Fitzherbert, E. B., Struebig, M. J., Morel, A., Danielsen, F., Bruehl, C. A., Donald, P.F., Phalan, B. (2008). How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23, pp. 538–545.

- Foose, T. J. (1991). Viable Population Strategies for Reintroduction Programmes. SYMPOSIA

- Gillespie, T. R. and Chapman, C. A. (2006). Prediction of Parasite Infection Dynamics in Primate Metapopulations Based on Attributes of Forest Fragmentation. CONSERVATION BIOLOGY 20 (2), pp.441-448.

- Goodland, R. (1982). Tribal Peoples and Economic Development: Human Ecologic Considerations. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Goossens, B., Funk, S. M., Vidal, C., Latour, S., Jamart, A., Ancrenaz, M., Wickings, E. J., Tutin, C. E. G. and Bruford, M. W. (2002). Measuring Genetic Diversity in Translocation Programmes: Principles and Application to a Chimpanzee Release Project. ANIMAL CONSERVATION (5(3)), pp.225-236.

- Greenpeace (2008). United Plantations Certified Despite Gross Violations of RSPO Standards, available to download from: http://www.greenpeace.org/international/press/reports/united-plantations-certified-d

- Hackel, J. (1999). Community Conservation and the Future of Africa’s Wildlife. Conservation Biology 13 (4), pp.726-734.

- Harrison, B. (1962). The Immediate Problem of the Orang-Utan. Malayan Nature Journal 16, pp.4-5.

- Hart, B. L. (1990). Behavioral Adaptations to Pathogens and Parasites: Five Strategies. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 14 (3), pp.273-294.

- ITTO (2005). Annual Review and Assessment of the World Timber Situation. Yokohama, Japan: International Tropical Timber Organization.

- Kalinowski, S. T. and Waples, R. S. (2002). Relationship of Effective to Census Size in Fluctuating Populations. Conservation Biology 16 (1), pp.129-136.

- Kleiman, D. G., Reading, R. P., Miller, B. J., Clark, T. W., Scott, J. M., Robinson, J., Wallace, R. L., Cabin, R. J. and Felleman, F. (2000). Improving the Evaluation of Conservation Programs. CONSERVATION BIOLOGY 14 (2), pp.356-365.

- Lande, R. and Barrowclough, G. F. (1987). Effective Population Size, Genetic Variation, and Their Use in Population Management. In: Soule, M. E. (ed.) Viable Populations for Conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mackinnon, K. and Mackinnon, J. (1991). Habitat Protection and Re- Introduction

- Madsen, T., Shine, R., Olsson, M. and Wittzell, H. (1999). Conservation Biology: Restoration of an Inbred Adder Population. NATURE 402, pp.34-35.

- May, R. M. (1991). The Role of Ecological Theory in Planning Re-Introduction of Endangered Species. SYMPOSIA OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON 62, pp.145-163.

- MCCONKEY, K. (2005). SUMATRAN ORANGUTAN (PONGO ABELII). IN: CALDECOTT, J. AND MILES, L. (EDS.) WORLD ATLAS OF GREAT APES AND THEIR CONSERVATION. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, PP.184-204.

- Moore, J. (2002). Parasites and the Behavior of Animals. New York: Oxford University Press

- Nelleman, C., Miles, L., Kaltenborn, B.P., Virtue, M., and Ahlenius, H. (Eds) (2007) The last stand of the orangutans – State of emergency: Illegal logging, fire and palm oil in Indonesia’s national parks. United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal, Norway

- Nettles, V. F. (1988). Wildlife Relocation: Disease Implications and Regulations. In: Proceedings of the 37th Annual Conference of the Wildlife Disease Association. Athens, Georgia.

- PanEco Foundation, Yayasan Ekosistem Lestari and ICRAF, Banda Aceh (2008). Vanishing Tripa: the Continuous Destruction of a unique ecosystem by palm oil plantations.

- Rijksen, H. D. and Meijaard, E. (1999). Our Vanishing Relative: The Status of Wild Orang-Utans at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishing.

- ROBERTSON J.M., VAN SCHAIK C.P. (2001). CAUSAL FACTORS UNDERLYING THE DRAMATIC DECLINE OF THE SUMATRAN ORANG-UTAN. ORYX, 35: PP. 26–38.

- Rodman, P. S. (1988). Diversity and Consistency in Ecology and Behavior. Orang-Utan Biology. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.31-51.

- Rosen, N., Russon, A. and Byers, O. (2001). Orangutan Reintroduction and Protection Workshop: Final

- Russon, A. E. (2002). Return of the Native: Cognition and Site-Specific Expertise in Orangutan Rehabilitation.

- Sarrazin, F. and Barbault, R. (1996). Reintroduction: Challenges and Lessons for Basic Ecology. TRENDS IN ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION (11(11)), pp.474-478.

- Singleton, I. and Aprianto, S. (2001). The Semi-Wild Orangutan Population at Bukit Lawang; a Valuable ‘Ekowisata’ Resource and Their Requirements.Unpublished paper presented at a “workshop on eco- tourism development at Bukit Lawang” held in Medan, April 2001. Medan, Indonesia: PanEco and Yayasan Ekosistem Lestari.

- Strier, K. B. (2007). Conservation. Primates in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.496-509.

- Sutherland, W. J. (1998). Conservation Science and Action. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Sutherland, W. J. (2000). The Conservation Handbook: Research, Management, and Policy. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- UNEP (2007). The Last Stand of the Orangutan – State of Emergency: Illegal Logging, Fire and Palm Oil in I

- van Beukering, P.J.H., Cesar, H.S.J., Janssen, M.A. (2003). Economic valuation of the Leuser

- Vasarhelyi, K. and Martin, R. D. (1994). Evolutionary Biology, Genetics and the Management of Endangered Primate Species. In: Olney, P. J. S., Mace, G. M. and Feistner, A. T. C. (eds.) Creative Conservation: Interactive Management of Wild and Captive Animals. London: Chapman & Hall, pp.118-143.

- Warren, K. S., Verschoor, E. J., Langenhuijzen, S., Heriyanto, Swan, R. A., Vigilant, L. and Heeney, J. L. (2001). Speciation and Intrasubspecific Variation of Bornean Orangutans, Pongo Pygmaeus Pygmaeus. MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND EVOLUTION (18(4)), pp.472-480.

- Wells, M. P. (1992). Biodiversity Conservation, Affluence and Poverty: Mismatched Costs and