- In 2016, scientists reported the largest die-off ever on the Great Barrier Reef.

- Some 70,000 people depend on the Great Barrier Reef for employment in the tourism industry, and it’s worth about $5 billion annually.

- The study’s authors report that repeated exposure to higher-than-normal sea temperatures submarines the corals’ chances at recovery. Even corals that survive don’t appear to be more tolerant of extreme temperatures, and high water quality – important for coral regrowth – doesn’t seem to offer much protection against bleaching.

Rising ocean temperatures are bleaching reefs around the world at unprecedented levels, and, with little standing in its way, this coral-killing force is unlikely to relent, according to a new study published today in the journal Nature.

The research examined the effects of three global bleaching events in past 20 years on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef – the largest in the world. They found that parts of the reef have been pummeled by repeated bleaching in 1998, 2002, and 2015-2016 – and further bleaching seems to be happening right now in early 2017. As climate change continues to warm the Earth, not much will hold back this reef-altering tide, according to the findings.

Higher-than-normal sea temperatures force corals, which are animals, to jettison the algae on which they depend for survival, draining the color from reefs and turning them white. If temperatures remain high, the corals typically die within months.

2016 was the most severe bleaching “by a long way” of the Great Barrier Reef that’s ever been recorded, said Sean Connolly, an ecologist at James Cook University and one of the study’s authors.

About 10 percent of the reef suffered “extreme bleaching” in 1998 and 2002, Connolly told Mongabay. “In 2016, that was almost 50 percent.”

That led to the largest die-off on the Great Barrier Reef in history, scientists reported in November 2016. The northern section was particularly hard-hit, losing 67 percent of its shallow water corals in 2016.

And there’s little doubt who the culprits are. “That’s us,” Connolly said. Before “detectable climate change,” the bleaching that did occur was usually confined to small areas over shorter time periods, he explained.

Only the human-induced warming of the planet, and by extension the increase in sea temperatures, could cause “significant bleaching on the scale of an entire reef system, much less significant bleaching all over the globe,” he said.

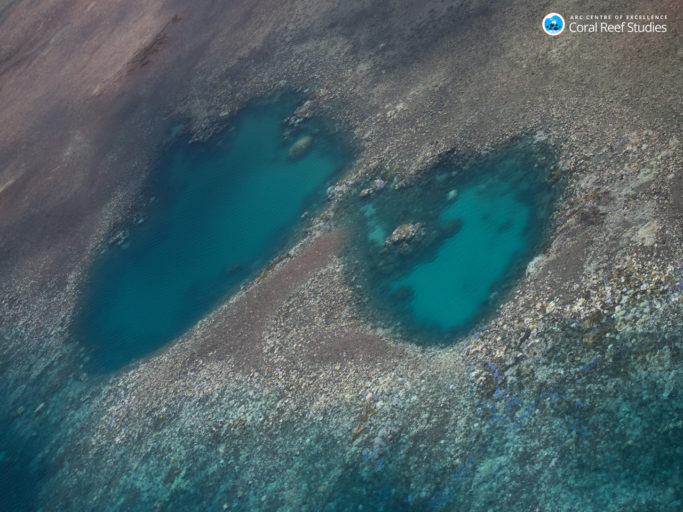

On Friday, the environmental NGO Greenpeace released new photographs of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef by conservation photographer and marine biologist Brett Monroe Garner that catalog the extensive bleaching of large stretches of the world’s largest living structure.

“I’ve been photographing this area of the reef for several years now and what we’re seeing is unprecedented,” Garner said in a statement.

“Just a few months ago, these corals were full of [color] and life,” Garner added. “Now, everywhere you look is white.”

Corals can recover, Connolly said, but it takes time. Even the fastest-growing species need 10-15 years to grow back. But if that resurgence is cut short by more bleaching, it could fundamentally change the composition of the reef and the ecosystem it anchors.

“You’re looking at an ecosystem that is going to provide less and less of the goods and services that we count on,” he said, pointing to the example of fisheries. Reefs provide critical habitat for young coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus), he said. When corals die, fewer of these fish survive to adulthood.

Additionally, around 70,000 people working in tourism depend on the Great Barrier Reef for employment. and it’s worth about $5 billion annually.

Connolly and his colleagues looked at possible protections or adaptations that might safeguard at least parts of the reef. But they “found no evidence” to support the hypothesis that corals that survive heat shocks would be more robust from future bleaching.

Even high-quality water doesn’t seem to buffer the reef against the bleaching effects of warmer seas. “That doesn’t mean that water quality’s not important,” he said. Reefs in poor quality water are often clogged with seaweed, which can stymy corals’ recovery. But again, the corals need time to rebuild.

“The corals aren’t getting the chance to bounce back from last year’s bleaching event,” Garner said. “If this is the new normal, we’re in trouble.”

CITATION:

- Hughes, T. P., Kerry, J. T., Álvarez-Noriega, M., Álvarez-Romero, J. G., Anderson, K. D., Baird, A. H., … Wilson, S. K. (2017). Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature, 543(7645), 373–377. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature21707

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.