The Madre de Dios region in Peru is recognized for its lush Amazon rainforests, meandering rivers and rich wildlife. But the region is also known for its artisanal gold mining, which employs the use of a harmful neurotoxin. Mercury is burned to extract the pure gold from metal and ore producing dangerous air-borne vapors that ultimately settle in nearby rivers.

“Mercury in all forms is a potent neurotoxin affecting the brain, central nervous system and major organs,” Luis Fernandez, an ecologist and research associate at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, told mongabay.com. “At extremely high exposure levels, mercury has been documented to cause paralysis, insanity, coma and death.”

However, mercury does not typically trigger dramatic immediate health effects, Fernandez continued. Instead it causes slow, insidious damage eventually resulting in reduction of life span and decreased quality of life.

Mercury is especially toxic to women of childbearing age, between the ages of 16 and 49. The toxin can be passed to the developing fetus across the placental barrier and cause severe and even permanent neurological damage to the unborn child. Although recognized as a major environmental health contaminant, the dangers of mercury are still actively debated in most mining regions in the Amazon.

Luis Fernandez taking water sample. Photo courtesy of: Luis Fernandez. |

“Because of the slow nature of the damage done by mercury, combined with the vague symptoms of early exposure, it is common that mercury contamination is overlooked, or, in many cases, actively denied as a real health threat,” Fernandez said.

But mercury is a health threat, especially in Puerto Maldonado, the capitol city of Madre de Dios. In 2009, Fernandez and a team of scientists found that many fish species sold in the markets of Madre de Dios contained high levels of mercury.

The study, led by the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Global Ecology, prompted the organization to establish the Carnegie Amazon Mercury Ecosystem Project (CAMEP) in 2012. Directed by Fernandez, CAMEP is made up of eight Peruvian universities and non-governmental organizations with Carnegie scientists.

The organization followed up on the 2009 report with two new studies in 2013. The investigations found high mercury concentrations not only in most of the wild caught fish sold in markets in Puerto Maldonado, but also in residents.

Mercury testing reveals larger problem

From May to August 2012, researchers offered adults in Puerto Maldonado free mercury hair testing, the main method used to determine mercury exposure in humans. The 226 participants completed a survey requesting information about individual fish consumption and mercury exposure history.

Researchers also analyzed mercury concentrations in the muscle tissue of commonly consumed fish. Fifteen different species of fish were purchased from several markets in the city during August 2012. Both the hair and fish samples were analyzed for total mercury at a laboratory established at the Environmental and Computational Chemistry Group, University of Cartagena in Colombia.

Taking hair samples to test for mercury. Photo courtesy of: Luis Fernandez. |

Researchers found that 9 of the 15 most consumed fish species sold in Puerto Maldonado had average levels of mercury above the international mercury reference limit of 0.3 part per million (ppm). In addition, the average mercury levels increased in 10 of the 11 fish species from 2009 to 2012, indicating the aquatic ecosystems are frequently altered by mercury, most likely due to artisanal gold mining activity.

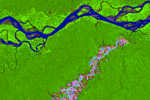

“Initially confined to areas around the main stem of the Madre de Dios River, mining has expanded into dozens of formerly pristine tributaries, rivers, streams and lakes all over the department of Madre de Dios,” Fernandez explains.

Mercury contamination is not restricted to wildlife. Many native communities and remote rural populations rely on wild caught fish for protein. Based on the survey, 92 percent of participants reported that they consume fish caught from local rivers and lakes on a regular basis. Sixty-four percent of the adults consume at least one high mercury fish species each week.

The hair tests found that 78 percent of adults had hair mercury concentrations above international mercury reference limits for human hair.

The average mercury concentrations of adults were 2.7 ppm – almost three times the reference value of 1 ppm. Mercury levels in human hair ranged from 0.02 ppm to an alarming high of 27.4 ppm. Women of childbearing age, the most vulnerable group, had the highest hair mercury levels with average levels of 3.0 ppm.

Carnegie Amazon Mercury Ecosystem Project (CAMEP) testing samples. Photo courtesy of: Luis Fernandez. |

In addition to the consumption of contaminated fish, 25 percent of the adults reported working directly in gold mining. Scientists believe the residents are exposed to the toxin from gold mining and the inhalation of airborne mercury in gold buying shops located in the center of the city.

“Gold shops boil off the mercury found in the amalgams that miners create in the mining areas and sell to gold merchants,” Fernandez explains. “Recent studies of gold shops in Peru indicate that an average gold shop can emit as much mercury as a 100 megawatt coal fired power plant each year.”

Mercury in the environment

Mercury is a naturally occurring element in the earth’s crust. While mercury is released into the environment due to the weathering of rocks and volcanic activity, the main cause of mercury release is human activity from coal-fired power stations, industrial processes and gold mining.

About 20 percent of the world’s gold is produced by the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The process is also responsible for the largest releases of mercury to the environment.

Local fish market in Peru. Photo courtesy of: Luis Fernandez.

|

When air-borne vapors settle in lake and river bottoms, the elemental mercury is converted by bacteria to methylmercury. Small fish consume the contaminated plants and algae that absorb methylmercury, and then the smaller contaminated fish are eaten by larger fish.

The fish higher up in the food chain can have mercury concentrations hundreds or thousands of times higher than fish lower down on the food chain, Fernandez said.

“This process is so efficient in many tropical rivers that a fish at the top of the food chain can have mercury levels millions of times higher than the mercury concentration of the river water in which they swim.”

Humans capture and eat the contaminated fish, the main source of exposure to humans, and absorb 98 percent of the mercury in the consumed fish. In humans the toxin can migrate through cells normally stopped by a protective barrier, but the health impact of mercury on fish and wildlife is not well studied.

Fish species with high mercury levels may have lower survivability, lower hatching rate and be more vulnerable to invasive competitors, Fernandez said. Contamination may also change community structure. Studies have found increased mortality of birds contaminated by mercury at very low concentrations.

In an upcoming study, CAMEP plans to analyze a larger number of fish species collected directly from the lakes and rivers to learn which waterways pose a greater health risk.

“Anthropogenic mercury emissions in Madre de Dios can be reduced by reducing or eliminating the mercury used in artisanal gold mining,” Fernandez said. “However, viable non-mercury technologies are not commonly used or currently affordable.”

Even with non-mercury technologies, Fernandez said uncontrolled artisanal gold mining can still produce massive environmental damage from deforestation, soil stripping, increased runoff and waste contamination.

Río Huaypetue gold mine in Peru. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Guacamayo mine site. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

CITATIONS: Carnegie Amazon Mercury Ecosystem Project (2013). Mercury in Madre de Dios: Mercury Concentrations in Fish and Humans in Puerto Maldonado. CAMEP Research Brief: March 2013, pp.1-2.

Ashe K (2012) Elevated Mercury Concentrations in Humans of Madre de Dios, Peru. PLoS ONE 7(3): e33305. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033305

Swenson JJ, Carter CE, Domec J-C, Delgado CI (2011) Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon: Global Prices, Deforestation, and Mercury Imports. PLoSONE 6(4): e18875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018875

Related articles

Brazilian agency rejects Canadian company’s bid to mine controversial Amazon dam site for gold

(02/13/2013) Brazil’s Federal Public Ministry rejected a proposed gold mining project adjacent to a controversial dam site in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, reports Amazon Watch, an environmental activist group that is campaigning against both the mine and the dam.

(12/08/2012) The world’s largest rainforest is in the midst of a mining boom fueled by high mineral prices, reveals a new assessment of the Amazon’s resources.

Gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: a view from the ground

(03/15/2012) On the back of a partially functioning motorcycle I fly down miles of winding footpath at high-speed through the dense Amazon rainforest, the driver never able to see more than several feet ahead. Myriads of bizarre creatures lie camouflaged amongst the dense vines and lush foliage; flocks of parrots fly overhead in rainbows of color; a moss-covered three-toed sloth dangles from an overhanging branch; a troop of red howler monkeys rumble continuously in the background; leafcutter ants form miles of crawling highways across the forest floor. Even the hot, wet air feels alive.

High gold price triggers rainforest devastation in Peru

(10/11/2011) As the price of gold inches upward on international markets, a dead zone is spreading across the southern Peruvian rain forest. Tourists flying to Manu or Tambopata, the crown jewels of the country’s Amazonian parks, get a jarring view of a muddy, cratered moonscape … and then another … and another in what the country boasts is its capital of biodiversity. While alluvial gold mining in the Amazon is probably older than the Incas, miners using motorized suction equipment, huge floating dredges and backhoes are plowing through the landscape on an unprecedented scale, leaving treeless scars visible from outer space. Sources close to the Peruvian Environment Ministry say the government is considering declaring an environmental emergency in the region, but emergency measures passed two years ago were not enough to contain the destruction, and some observers doubt that a new decree would have any more impact.

Demand for gold pushing deforestation in Peruvian Amazon

(04/19/2011) Deforestation is on the rise in Peru’s Madre de Dios region from illegal, small-scale, and dangerous gold mining. In some areas forest loss has increased up to six times. But the loss of forest is only the beginning; the unregulated mining is likely leaching mercury into the air, soil, and water, contaminating the region and imperiling its people. Using satellite imagery from NASA, researchers were able to follow rising deforestation due to artisanal gold mining in Peru. According the study, published in PLoS ONE, Two large mining sites saw the loss of 7,000 hectares of forest (15,200 acres)—an area larger than Bermuda—between 2003 and 2009.