Organic farm in Montana. Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

With the worst effects of climate change, we are seeing how pollution hurts both human health and the environment but there is good news: a new study shows that organic farming stores more greenhouse gases in the soil than non-organic farming. By switching to organic methods, many farmers across the globe may be helping to solve the climate crisis at the same time as they improve soil quality and avoid the use of pesticides.

“Organic agriculture is more than just producing good and healthy food. It is also good for soil quality and fertility and climate change adaptation and mitigation,” says study author Andreas Gattinger of The Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

Gattinger and his team performed a meta-analysis of other peer-reviewed studies of organic farming that quantified how much carbon was being stored by organic farmers. Meta-analysis is a type of “bird’s eye view” study that congregates findings from multiple studies. While the details of individual studies may be obscured in a search for trends, Andreas told mongabay.com that a good meta-analysis always “deliver[s] the core data of the individual studies to give anybody the chance for tracing back and re-calculation” in order to “deliver evidence-based, quantitative figures on a certain effect or phenomenon.”

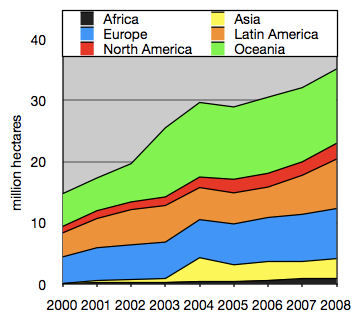

The results of Gattinger’s meta-analysis show an overall positive worldwide trend towards an increase in organic agriculture (37 million hectares or 0.9 percent of total world agricultural land). The authors’ meta-analysis suggests that organic farming allows more carbon to be stored in the soil than conventional farming. Instead of carbon heating up the atmosphere, it is being stored in the soil, which acts like a carbon sink.

Andreas Gattinger assessing soil quality on his organic farm in Germany. Photo by: Karen Heinen. |

The researchers estimate that by using a combination of livestock plus rotating crops (mixed farming), more carbon can be stored in organically farmed soil than any farming system relying on the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and plant protection chemicals. Their results show that 0.37 gigatons of carbon were being sequestered per year globally (0.03 gigaton of carbon in Europe, 0.04 gigaton of carbon in the United States), thus offsetting 3% of current total greenhouse gas emissions (2.3% for Europe, 2.3% for the United States), or 25% of total current agricultural emissions (23% for Europe, 36% for the United States). In fact, the researchers write that the cumulative mitigation by organic farming up to 2030 would contribute 13% to the cumulative reductions that would be necessary by then to stay on the path to keep temperatures from rising two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Researchers say this meta-analysis provides a strong argument in favor of organic farming.

“[Since] pristine land uses can only feed hunters and gatherers and sometimes animal herders. Organic farming is somehow in between…intensive agriculture and [the] original state of land,” Gattinger told mongabay.com.

Still, there remain many obstacles to a quick industry-wide transition to organic farming. Brian Baker, also of The Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, told mongabay.com that within the United States “each cropping system, each animal production system, each food and fiber product needs to be looked at for specific obstacles”.

He sees the greatest barriers to the adoption of organic food as economic, educational, technical and institutional.

The economics of organic farming currently favor heavily subsidized factory farming. Baker says that “if [such] operations were required to pay full costs for compliance with environmental laws, it does not appear that such factory farms would be economically viable.”

He explains that organic farmers have the burden to prove that they are organic and pay those transaction costs.

Growth of organic farming since 2000. |

“If non-organic farmers had to be equally accountable and transparent about the sustainability of their practices and pay for their environmental impacts, then organic farming would be a more attractive alternative.”

Anyone who buys food in the marketplace knows that organic products cost more. But Baker argues that this is a problem of incorrect pricing.

“Organic food costs more to produce. Non-organic foods have hidden costs, like pollution from pesticides and chemical fertilizers. The farmers who apply these chemicals do not pay for water pollution, the increases in cancer rates due to exposure to carcinogens—or less directly the increase in greenhouse gases emissions from manufacture of agricultural chemicals…” he says, adding that, “If organic food cost less to produce than non-organic food, a lot more people would eat it and a lot more people would grow it. Changing the prices of pesticides and fertilizers to pay for the problems they cause would reduce their use, increase the cost to produce non-organic food, and make organic food more competitive.”

Baker also sees the crisis in organic farming as a cultural and educational problem, symptomatic of a society which invested heavily in energy and input-intensive industrial approaches over traditional, organic, mentor-based approaches, making a large-scale transition difficult. He tells mongabay.com that while a transition towards organic farming is finally being considered, it is a cultural one that can’t happen overnight.

“Organic farming has more often been taught by mentoring farmers and there are not enough mentors to go around…[it] requires a more complicated understanding of ecological systems and is more management intensive,” he explains. “Agricultural education programs have only recently started to recognize organic agriculture as legitimate…most funding for farming research has gone into research for approaches that are not organic or sustainable…For over 60 years, the focus of research was on input-intensive approaches that were not compatible with organic farming systems. With the depletion of natural resources, there is a growing realization that this approach is not going to be sustainable in the long run.”

Baker sees a transition to organic farming as likely “by paying the true cost of food production, teaching future farmers how to farm organically, [with greater] research in technology and innovation that benefits all farmers, including organic farmers, and at least a level playing field with respect to government programs that currently support non-organic farming.”

The authors’ study should be of great value to decision makers, like those on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), who with this study may begin to quantify the role that organic farming may play in solving the climate crisis. Gattinger says he hopes the study will “have an impact on agricultural, environmental, and climate policies and supporting schemes, in which the contribution of organic farming should be more acknowledged.”

Table shows the total organic agricultural land area, which while positive, also shows there is much room for growth.

Related articles

Organic yields lag behind industrial farming, but that’s not the whole story

(04/26/2012) In general, industrial agriculture beats organic farming in yields, according to a comprehensive new study in Nature. The study adds new data to the sometimes heated debate of organic versus conventional farming. Proponents of organic farming argue that these practices are environmentally friendly, sustainable over the long-term, and provide a number of social goods. However, critics argue that organic farming requires more land, thereby increasing global deforestation, which offsets any other environmental benefits of organic food production. At stake is whether organic or conventional is capable of feeding the world’s seven billion people (and rising), including increasing demand for energy-intensive foods like meat in the developing world.

Fertilizer trees boost yields in Africa

(10/16/2011) Fertilizer trees—which fix nitrogen in the soil—have improved crops yields in five African countries, according to a new study in the International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability. In some cases yields have doubled with the simple addition of nitrogen-soaking trees. The research found that fertilizer trees could play a role in alleviating hunger on the continent while improving environmental conditions.

Five ways to feed billions without trashing the planet

(10/13/2011) At the end of this month the UN predicts global population will hit 7 billion people, having doubled from 3.5 billion in less than 50 years. Yet even as the Earth hits this new milestone, one billion people do not have enough food; meanwhile the rapid expansion of agriculture is one of the leading causes of global environmental degradation, including greenhouse gas emissions, destruction of forests, marine pollution, mass extinction, water scarcity, and soil degradation. So, how do we feed the human population—which continues to rise and is expected to hit nine billion by 2050—while preserving the multitude of ecosystem services that support global food production? A new study in Nature proposes a five-point plan to this dilemma.

Organic farming can be more profitable in the long-term than conventional agriculture

(09/01/2011) Organic farming is more profitable and economically secure than conventional farming even over the long-term, according to a new study in Agronomy Journal. Using experimental farm plots, researchers with the University of Minnesota found that organic beat conventional even if organic price premiums (i.e. customers willing to pay more for organic) were to drop as much as 50 percent.

(09/01/2011) Given that we have very likely entered an age of mass extinction—and human population continues to rise (not unrelated)—researchers are scrambling to determine the best methods to save the world’s suffering species. In the midst of this debate, a new study in Science, which is bound to have detractors, has found that setting aside land for strict protection coupled with intensive farming is the best way to both preserve species and feed a growing human world. However, other researchers say the study is missing the point, both on global hunger and biodiversity.

Growing strawberries organically yields more nutritious fruit and healthier soil

(11/08/2010) Strawberry plants grown on commercial organic farms yield higher-quality fruit and have healthier soil than those grown conventionally, according to a study published on 1 September in the journal PLoS One. The research suggests that sustainable farming practices can produce nutritious fruit, if farmers manage soil and its beneficial microbes properly. This is among the most comprehensive studies to investigate how conventional and organic farming methods affect both fruit and soil quality.

Farms in the sky, an interview with Dickson Despommier

(10/12/2010) To solve today’s environmental crises—climate change, deforestation, mass extinction, and marine degradation—while feeding a growing population (on its way to 9 billion) will require not only thinking outside the box, but a “new box altogether” according to Dr. Dickson Despommier, author of the new book, The Vertical Farm. Exciting policy-makers and environmentalists, Despommier’s bold idea for skyscrapers devoted to agriculture is certainly thinking outside the box.

Could forest conservation payments undermine organic agriculture?

(09/07/2010) Forest carbon payment programs like the proposed reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) mechanism could put pressure on wildlife-friendly farming techniques by increasing the need to intensify agricultural production, warns a paper published this June in Conservation Biology. The paper, written by Jaboury Ghazoul and Lian Pin Koh of ETH Zurich and myself in September 2009, posits that by increasing the opportunity cost of conversion of forest land for agriculture, REDD will potentially constrain the amount of land available to meet growing demand for food. Because organic agriculture and other biodiversity-friendly farming practices generally have lower yields than industrial agriculture, REDD will therefore encourage a shift toward from more productive forms of food production.