Scientists convening in Bali expressed a range of concerns over a proposed mechanism for mitigating climate change through forest conservation, but some remained hopeful the idea could deliver long-term protection to forests, ease the transition to a low-carbon economy, and generate benefits to forest-dependent people.

Presenting at the annual Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, scientists and policy experts warned that the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) program outlined in international climate talks could fail to achieve the desired outcome of protecting forests, while having detrimental impacts on biodiversity and local livelihoods, if it isn’t properly designed or excludes critical safeguards. Some researchers argued that the economics of REDD may fall short of competing with returns from other forms of land use, including logging and plantation development, while others said that a successful REDD program could undermine wildlife-friendly farming approaches, promote conversion of low carbon landscapes for industrial tree-planting projects, and shift conservation priorities toward carbon-dense ecosystems.

Tangkoko, Sulawesi in Indonesia |

“REDD is a potentially excellent mechanism by which to address GHG emissions while incidentally contributing to biodiversity conservation and the maintenance of ecosystem services,” said Jaboury Ghazoul, an ecologist at ETH Zurich, who discussed potential unrealized costs of REDD. “There are, however, challenges to overcome, ranging from the administrative and technical implementation of REDD, to the wider knock-on effects on downstream livelihoods and regional development. As scientists keen to see the successful implementation of REDD we must also recognize and grapple with its wider challenges.”

Several presenters used the host country of Indonesia, which recently signed a one billion dollar deal with Norway to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, to provide context of the types of problems that could befall a poorly designed and implemented REDD mechanism.

Financial fraud

Christopher Barr, a former CIFOR researcher, pointed to financial mismanagement and outright fraud in Indonesia’s Reforestation Fund as an example. He noted that during former Indonesian President Soeharto’s reign the country’s Reforestation Fund suffered losses of more than $5.2 billion – much of it to corruption and fraud. Although the current administration has taken steps to improve financial controls, hHundreds of millions more have been misappropriated or wasted on poorly managed projects in recent years.

Deforestation for palm oil production in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo |

According to Barr, “Indonesia’s experience with the Reforestation Fund provides important insights into the government’s capacity to manage and allocate a large stream of funds in the country’s forestry sector. It demonstrates that existing administrative structures are ill-equipped to handle the influx of REDD+ funds and will need to be strengthened. Just as mechanisms are being developed to measure and verify changes in forest carbon emissions, effective systems are urgently needed for financial verification as well.”

Roger James of Conservation International echoed these concerns in a presentation on the REDD readiness of Papua New Guinea, a country that on the international stage has led the push for the payments for forest conservation mechanism, but done little at home to support the scheme at home. James highlighted examples of fraud revolving around the PNG forest carbon sector as well as the rise of a REDD “cargo cult”, whereby the expectations for “sky money” have risen so high they can never be met. He mentioned that the fundamentals of REDD were poorly understood in many parts of the country, with some villagers talking of getting carbon money for their forests and then selling the trees to loggers. James said that given the uncertainty around REDD and lack of capacity within PNG, conservationists working in country should focus on making biodiversity conservation effective rather than waiting for carbon finance.

Knock-on effects

Jaboury Ghazoul said that policymakers supporting REDD may be greatly undervaluing the opportunity costs of forgoing logging and conversion of primary forests. Looking at Indonesia, he highlighted potential job losses, shifts in overseas development aid regimes linked to forestry, and impacts on downstream industries as examples. Ghazoul also said that by increasing the opportunity cost of land use, REDD could put pressure on “wildlife-friendly” farming approaches like organic agriculture.

|

“Two important challenges facing human society is reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the need to meet food demands for a growing population. REDD is a mechanism that can substantially contribute to the first challenge, but by doing so might constrain our ability to manage the second.”

“An expanding population will need more food, which is likely to require more agricultural land at the expense of forests, something that would conflict with REDD. Resolving this conflict requires us to produce more food from less land – in other words the intensification of land use. While this may allow us to reconcile one conflict, it opens us up to another – that of maintaining diverse agricultural landscapes that support biodiversity. So, while promoting REDD to preserve forests we might inadvertently be driving agricultural intensification and the loss of biodiversity in human dominated landscape mosaics. REDD++, which accounts for carbon values of agricultural as well as forest landscapes, offers exciting possibilities to circumvent this second challenge.”

Carbon conservation not necessarily aligned with biodiversity conservation

Stuart Pimm, a Duke University scientist, added that biodiversity hotspots not always aligned with the most carbon-dense regions of the world, leading to risk that REDD focus could shift priorities away from species conservation, a sentiment shared by Elizabeth Losos, president of the Organization for Tropical Studies Environmental Sciences & Policy.

Francis “Jack” Putz, an ecologist from the University of Florida, urged caution on what he termed the “arborealization” of conservation agendas. Putz fears that new emphasis on REDD will trigger afforestation of low-carbon ecosystems like savannas, jeopardizing biodiversity.

“We need to be careful not to undervalue low carbon landscapes,” he said.

Still hope for REDD

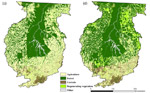

Not all the news was negative however. Greg Asner discussed breakthroughs in remote monitoring of forests, including high resolution, 3-D mapping of forest cover using airplane-based LiDAR sensors and advanced processing of satellite imagery. The image processing technology, which is currently being used in the Amazon to detect both deforestation and small-scale forest disturbance caused by selective logging, will soon be available online for Southeast Asia and Africa. Asner said LiDAR is now allowing researchers to conduct biological inventories of tree species from thousands of feet above the canopy at a rate of more than 10,000 hectares per day.

Related: Brazil could halt Amazon deforestation within a decade |

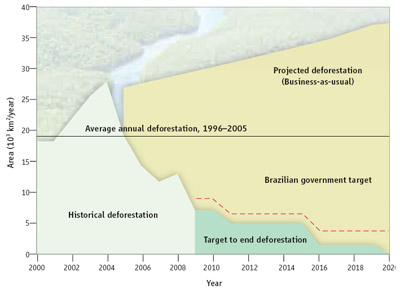

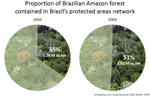

Dan Nepstad, a researcher at the Woods Hole Research Center, was upbeat about the prospects of carbon finance for protecting rainforests. Nepstad detailed the sharp drop in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon in recent years and said that REDD could play a key part to consolidating gains in the region, perhaps bringing an end to deforestation within a generation, while helping the world transition to a low carbon economy. He cautioned that REDD could be “messy” from the get-go, but the potential benefits are immense.

“We need to approach REDD as a skinny pack donkey upon which we are loading concerns for food security, biodiversity (in savannas and grasslands), land rights, and other issues. The risk is that we will overload the beast and keep it from making any progress or, worse, killing,” he said. “REDD must be viewed not as the latest “silver bullet” for protecting tropical forests. Rather, REDD is the first component of a new rural development paradigm that is focused on the maintenance of forests, but that must eventually culminate in even greater biodiversity protection, increased agricultural output, and stronger control over forests and lands by their traditional and indigenous inhabitants.”

Rainforest in Sumatra |

Claudia Stickler, also a Woods Hole Research Center scientist, added that carbon finance could be a path to reconcile seemingly conflicting national targets for Brazil: a 30 increase in agricultural production by 2019 and a 70 percent reduction in deforestation by 2020. She said REDD payments could provide a key incentive covert the largest drivers of deforestation in the Amazon — ranchers and farmers — into forest protectors.

“It’s important to understand the true potential of REDD+. If done properly, it could represent a sea-change in the prevailing conservation and economic/social development paradigms, which have largely separated these two agendas and/or relegated their conception and execution to relatively small-scale projects and initiatives,” she told mongabay.com.

“Clearly, there are a number of critical issues to deal with—not the least of which is the depth and breadth of social engagement that is necessary to make policies associated with REDD implementation stick—but the opportunity to achieve forest governance on a broad scale should not be jettisoned for fear that these obstacles will prove insurmountable.”

Making logging a part of the solution

|

Several ATBC presenters emphasized the importance of “sustainable forest management” or low-impact logging and reforestation under the REDD+ mechanism. Bronson Griscom of The Nature Conservancy, said that reduced impact logging would increase returns from carbon conservation, improving its economic performance and reducing the risk that landowners would abandon forest conservation commitments. Griscom argued that careful logging could help mitigate the issue of international leakage, since forests would continue to supply timber to meet global demand. Lex Hovani, also of The Nature Conservancy, added that low-impact logging could generate income for communities and forest managers once REDD payments are phased out sometime after 2030.

“We need to think not only about how REDD is going to start, but how REDD is going to end,” he said.

Putz said that reduced impact logging (RIL) techniques can significantly reduce emissions relative to conventional logging. He estimated that RIL could cut global emissions in legal logging concessions alone by 160-360 million tons per year. Several other researchers reported that selectively logged forest retains 80-90 percent of the species found in primary forests, but cautioned that single-species plantations — like acacia, rubber, and oil palm plantations are biological deserts.

“Plantations aren’t forests,” said Putz.

The ATBC meeting wraps up tomorrow. A declaration on the billion dollar Norway-Indonesia forest partnership is expected at the conclusion of the conference.

Related articles

Indonesia’s plan to save its rainforests

(06/14/2010) Late last year Indonesia made global headlines with a bold pledge to reduce deforestation, which claimed nearly 28 million hectares (108,000 square miles) of forest between 1990 and 2005 and is the source of about 80 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said Indonesia would voluntarily cut emissions 26 percent — and up to 41 percent with sufficient international support — from a projected baseline by 2020. Last month, Indonesia began to finally detail its plan, which includes a two-year moratorium on new forestry concession on rainforest lands and peat swamps and will be supported over the next five years by a one billion dollar contribution by Norway, under the Scandinavian nation’s International Climate and Forests Initiative. In an interview with mongabay.com, Agus Purnomo and Yani Saloh of Indonesia’s National Climate Change Council to the President discussed the new forest program and Norway’s billion dollar commitment.

(05/03/2010) Over the past 30 years billions of dollars has been committed to global conservation efforts, yet forests continue to fall, largely a consequence of economic drivers, including surging global demand for food and fuel. With consumption expected to far outstrip population growth due to rising affluence in developing countries, there would seem to be little hope of slowing tropical forest loss. But some observers see new reason for optimism—chiefly a new push to make forests more valuable as living entities than chopped down for the production of timber, animal feed, biofuels, and meat. While are innumerable reasons for protecting forests—including aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and moral—most land use decisions boil down to economics. Therefore creating economic incentives to maintaining forests is key to saving them. Leading the effort to develop markets ecosystem services is Forest Trends, a Washington D.C.-based NGO that also organizes the Katoomba group, a forum that brings together a wide variety of forest stakeholders, including the private sector, local communities, indigenous people, policymakers, international development institutions, funders, conservationists, and activists.

Chaos and the Accord: Climate Change, Tropical Forests and REDD+ after Copenhagen

(04/06/2010) The Copenhagen Accord, forged at COP15 upended international efforts to confront

climate change. Never before have 115 Heads of State gathered together at one

time, let alone for the singular purpose of crafting a new climate change

agreement. Even though the new Accord is still in intensive care, two things

are already clear. First, we have entered an entirely new world. And second,

tropical forests have the greatest potential to breathe life into the new

agreement.

Brazil could halt Amazon deforestation within a decade

(12/03/2009) Funds generated under a U.S. cap-and-trade or a broader U.N.-supported scheme to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and degradation (“REDD”) could play a critical role in bringing deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon to a halt, reports a team writing in the journal Science. But the window of opportunity is short — Brazil has a two to three year window to take actions that would end Amazon deforestation within a decade.

In absence of measures to address consumption, REDD may fail to protect forests

(12/02/2009) Rising demand for timber and agricultural products could work against a proposed initiative to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD), warns a new report from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA). The briefing, Putting the Brakes on Drivers of Forest Destruction: A Shared Responsibility, says that investment in REDD will not be enough to protect forests if the underlying drivers of deforestation — namely consumption — are not addressed. It urges negotiators to re-insert critical text that has been dropped from the working text on REDD ahead of next week’s climate change conferences in Copenhagen.

(11/17/2009) Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation [REDD] programs that include landowners will conserve more habitat and ensure greater ecosystem services function than programs that focus solely on protected areas, report researchers from the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC), the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM), and the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG).

(11/03/2009) Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), a climate change mechanism proposed by the U.N., has been widely lauded for its potential to simultaneously deliver a variety of benefits at multiple scales. But serious questions remain, especially in regard to local communities. Will they benefit from REDD? While much lip-service is paid to community involvement in REDD projects, many developers approach local communities as an afterthought. Priorities lie in measuring the carbon sequestered in a forest area, lining up financing, and making marketing arrangements, rather than working out what local people — the ones who are often cutting down trees — actually need in order to keep forests standing. This sets the stage for conflict, which reduces the likelihood that a project will successfully reduce deforestation for the 15-30 year life of a forest carbon project. Brodie Ferguson, a Stanford University-trained anthropologist whose work has focused on forced displacement of rural communities in conflict regions in Colombia, understands this well. Ferguson is working to establish a REDD project in an unlikely place: Colombia’s Chocó, a region of diverse coastal ecosystems with some of the highest levels of endemism in the world that until just a few years ago was the domain of anti-government guerillas and right-wing death squads.

Are we on the brink of saving rainforests?

(07/22/2009) Until now saving rainforests seemed like an impossible mission. But the world is now warming to the idea that a proposed solution to help address climate change could offer a new way to unlock the value of forest without cutting it down.Deep in the Brazilian Amazon, members of the Surui tribe are developing a scheme that will reward them for protecting their rainforest home from encroachment by ranchers and illegal loggers. The project, initiated by the Surui themselves, will bring jobs as park guards and deliver health clinics, computers, and schools that will help youths retain traditional knowledge and cultural ties to the forest. Surprisingly, the states of California, Wisconsin and Illinois may finance the endeavor as part of their climate change mitigation programs.