Protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon are proving highly effective in reducing forest loss in Earth’s largest rainforest, reports a new study based on analysis of deforestation trends in and around indigenous territories, parks, military holdings, and sustainable use reserves.

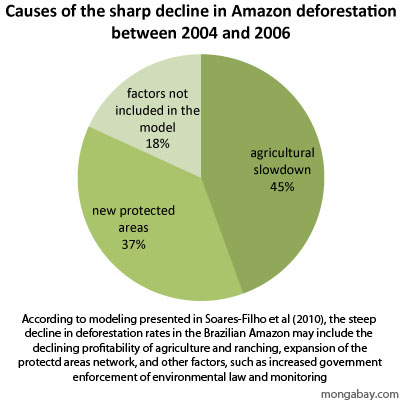

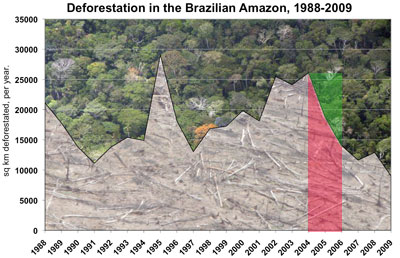

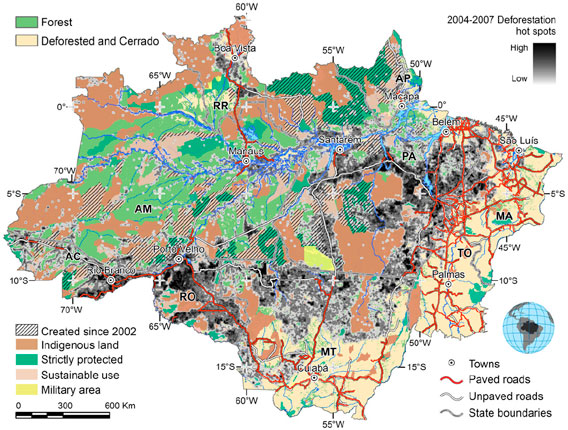

The research, published in the early edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, finds that 37 percent of the recent decline in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon can be attributed to newly established protected areas. Brazil designated some 709,000 square kilometers (274,000 sq mi) of Amazon forest — an area larger than the state of Texas — between 2002 and 2009 under its Amazon Protected Areas Program (ARPA). Meanwhile deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell by nearly three-quarters between 2004 and 2009.

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, 1988-2009, with 2004 to 2006 highlighted.

|

The paper — co-authored by 12 researchers across five institutions in Brazil and the United States — concludes that 115 of the 206 protected areas established since 1999 have showed increased effectiveness in reducing deforestation, without displacing forest clearing to unprotected areas (a concept known as “leakage”). The results indicate that newly protected areas in Brazil are more than “paper parks” — reserves that are so ineffective they seem only to exist on paper. Indigenous reserves were found to be the most effective form of protected area in reducing deforestation.

Looking towards the Brazilian government’s ambitious plan to reduce annual deforestation rates 80 percent from a historical baseline of 19,500 square kilometers per year by 2020, the authors estimate that the protected areas established between 2003 and 2008 will reduce deforestation of 180,000 to 360,000 square kilometers of rainforest by 2050, avoiding emissions of 2.2 to 4.4 billion metric tons of carbon. Factoring in the 127,000 sq km of new protected areas currently being established under ARPA, the authors say the program would reduce carbon emissions by 5 billion metric tons by 2050, or roughly 16% of the current annual emissions from human activities.

But the conservation program entails significant economic costs in terms of protected areas management as well as activities forgone by loggers, ranchers, and farmers. The cost of maintaining the carbon storage potential and biological productivity of the forest via ARPA over the ext 30 years would be around $150 billion, according to the study’s calculations.

But while the bill may seem high, it works out to $5.40 per ton of carbon — far cheaper than most readily available emissions mitigation approaches. The authors therefore argue that REDD — a proposed climate change mitigation mechanism that would see industrialized countries compensate tropical nations for reducing deforestation — could help pay for the protected areas program.

“Investments to reduce 9–23 [billion tons] of CO2 emissions that would be expected to occur over a period of 30 years if protected areas did not exist would amount to US$27–84 billion,” the authors write. “With annual payments representing about 1% of current global investments in clean energy (US$148.4 billion), reducing emissions with Amazon protected areas would be equivalent to reducing deforestation emissions by 10% worldwide but could be more cost effective.”

The researchers note that the economic costs of program would be offset by “the economic benefits of forest maintenance, including protection of rainfall regimes, reduction of fire incidence and associated losses to human health, agricultural systems, and forestry potential, and the value of biodiversity itself.”

Brazilian Amazon protected areas and 2004–2007 deforestation hot spots. The Arc of Deforestation comprises eastern, southern, and southwestern Amazon. AC, Acre; AM, Amazonas; AP, Amapá; MA, Maranhão; MT, Mato Grosso; PA, Pará; RO, Rondônia; RR, Roraima; TO, Tocantins. |

“These benefits are difficult to quantify and generally are omitted from economic evaluations of REDD (29). In other words, assessments of the economic opportunity costs of PAs must be balanced by both the economic benefits associated with forest conservation and the programmatic costs of reducing deforestation, which can be quite small.”

The authors conclude by noting that Brazil’s protected area network alone will not be enough to save the Amazon. Efforts to protect the forest must include private landowners, who could be enticed by economic incentives generated through market access and price premiums for responsibly-produced timber and agricultural products. Improved land use zoning, monitoring and law enforcement are also critical to maintaining the Amazon as a healthy and productive ecosystem.

CITATION: Britaldo Soares-Filho, Paulo Moutinho, Daniel Nepstad, Anthony Anderson, Hermann Rodrigues, Ricardo Garcia, Laura Dietzsch, Frank Merry, Maria Bowman, Letícia Hissa, Rafaella Silvestrini, and Cláudio Maretti (2010). Role of Brazilian Amazon protected areas in climate change mitigation. PNAS www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0913048107

Related articles