In the aftermath of a military coup last March, Madagascar’s rainforests have been pillaged for precious hardwoods, including rosewood and ebony. Tens of thousands of hectares have been affected, including some of the island’s most biologically diverse national parks: Marojejy, Masoala, and Makira. Illegal logging has also spurred the rise of a commercial bushmeat trade. Hunters are now slaughtering rare and gentle lemurs for restaurants.

Furthermore, armed gangs marauding through national parks have hurt tourism, a critical source of direct and indirect income for many Malagasy, as the people of Madagascar are known. Rosewood traders have intimidated, and in some cases even beaten, those who have attempted to stop the plunder. Conservation NGOs operating in affected areas have been rendered impotent because the ruling “transition authority” — made up of the coup leaders — is now taking an active role in the logging, possibly as a means to finance upcoming elections they hope will legitimize their power grab. To this end, Andry Rajoelina, the head of the transition authority, recently authorized the export of rosewood logs, a traffic previously banned. This triggered a frenzy of logging that has gone underreported due to the regime’s crackdown on the press. The perceived illegitimacy of the Rajoelina regime had led foreign donors to suspend most aid to the country, undercutting environmental protection programs and law enforcement. The situation is dire.

Since the coup there has been an upswing in commercial poaching of lemurs. Lemurs are increasingly butchered for novelty dishes, rather than subsistence. |

International uproar driven by international media attention and a campaign organized by Ecological Internet, an activist group, has managed to shut down rosewood exports since December 3 of last year by pressuring shipping companies, but stockpiles continue to build with loggers emboldened by Rajoelina’s export authorization order. Traders are confident that if they wait long enough, they will eventually be able to ship the contraband timber.

To date there seem to be few options in addressing the logging crisis. The entities that would normally step in are unable or unwilling to do so: local NGOs and communities are powerless in the face of violence and government opposition, international NGOs (with the exception of the Missouri Botanical Garden) fear jeopardizing their projects by taking a stand, donor governments and agencies refuse to support the unelected Rajoelina, and the transition authority is complicit. Is there a solution?

I don’t know if there is, but here is an idea: an absolute moratorium on logging combined with amnesty from prosecution for traders and a reforestation program funded by sales of illegally logged timber. The moratorium would be effective immediately with violations punishable by a long prison sentence. Any rosewood logs currently awaiting shipment in Vohemar, Tamatave, and other specified towns would be marked with a counterfeit-proof code (required for export clearance) and recorded in a digital tracking system. The logs would be auctioned via a transparent market system — the price and the log code would be recorded and publicly available.

Rosewood logs.

|

Revenue from the sales would be divided under a pre-defined system. The trader, who was engaged in an illegal activity but would win amnesty from prosecution for prior logging-related crimes, would get the smallest take: perhaps 1-3 percent of the sale price of around $1,300 for a log of average size. A larger proportion (perhaps 7-9 percent) would be set aside for administration of the program, while the reminder would be put into a trust fund split between environmental law enforcement and reforestation with native species. Both activities would provide job opportunities for local communities. Payments should be structured to last for a minimum of 20 years to ensure sustainability. For tree-planting outside protected areas could be additional income generated from sustainable forest management (after 20 years) or payments for forest carbon, provided such a system emerges under an eventual global climate framework. Transparency would be essential and there would need to be severe penalties for cheating. Logs delivered after the amnesty date would be confiscated (with proceeds going to communities) and the trader arrested.

The beauty of such a program is that it would simultaneously help restore Madagascar’s forests—the basis for ecotourism—and compensate people in local communities who have suffered most from illegal logging. Furthermore, the process could be designed in a way to be apolitical, in that it would be self-funded and independent of whatever regime is in power. But politicians would still benefit from their seeming magnanimity, which would enable them to claim one small area of progress in what has otherwise been a disastrous year for the Malagasy people.

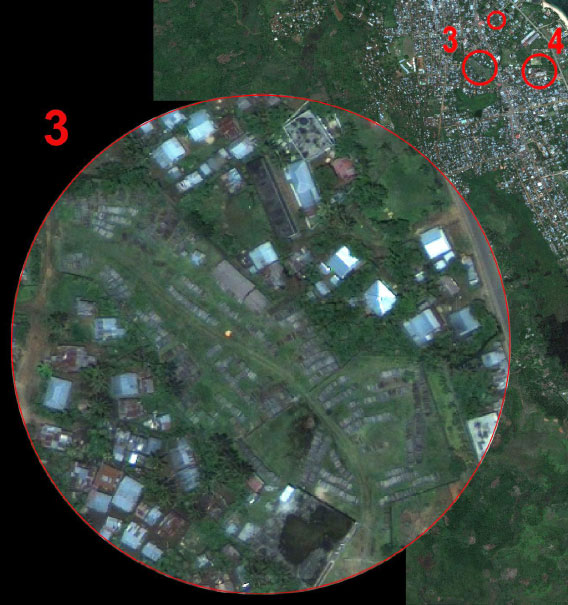

Analysts in Europe and the United States are using high resolution satellite imagery to identify and track shipments of timber illegally logged from rainforest parks in Madagascar. The images could be used to help prosecute traders involved in trafficking and put pressure on companies using rosewood sourced from Madagascar. These GeoEye Satellite images from December 2 of Antalaha identify several timber depots. The four close-ups with a radius of 100m show rosewood stacks. Peter Raven, Pete Lowry, and others at the Missouri Botanical Garden have been working with Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland to prepare and analyze images from the GeoEye-1 satellite. The Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the only major Western NGOs working to address the logging crisis in Madagascar. |

Yes the challenges of setting up an integrated moratorium-conservation-amnesty-reforestation (MCAR) program are daunting. It would require governance, which presently non-existent in northeastern Madagascar; deal-making with the current regime; and careful execution to ensure it does not exacerbate the situation by creating perverse incentives for logging. MCAR would also require a credible monitoring and verification system to establish what logs qualify. Perhaps this effort could be initially supported by high-resolution GeoEye satellite imagery, acquisition and analysis of which could be funded by the large international NGOs that have been raising money for Madagascar but failing to put it to use effectively in stopping the logging crisis. Corruption would remain a great concern but could be tempered by controls to ensure transparency.

Overall, the benefits of using illegally logged timber to finance community-based restoration of forests in northeastern Madagascar potentially outweighs the alternative of allowing the timber to be exported at immense profit to criminal syndicates, politicians, and business elites. While Madagascar was long known as a graveyard for grand ideas, progress in the past decade has offered hope. In that time Madagascar went from the pariah of conservation to a model. There’s reason to believe history can be repeated.

|

An alternative proposal: the rosewood counterpart fund An inspiration for this commentary was a paper, A forest counterpart fund: Madagascar’s wounded forests can erase the debt owed to them while securing their future, with support from the citizens of Madagascar, published by Lucienne Wilmé, Derek Schuurman, and Porter P. Lowry II. The authors argue for a forest counterpart fund that would be used to underwrite “charitable works to compensate for the damages and losses inflicted on the victims of the illegal exploitation of precious woods.” Schuurman told mongabay.com that “Madagascar has a fair history with regards ‘counterpart funds’ such as that proposed in the paper, and the process could be organized with local expertize drawn on in-country.” The paper, which gives background on the rosewood trade, will be published by Lemur News. |

Satellites being used to track illegal logging, rosewood trafficking in Madagascar

(01/28/2010) Analysts in Europe and the United States are using high resolution satellite imagery to identify and track shipments of timber illegally logged from rainforest parks in Madagascar. The images could be used to help prosecute traders involved in trafficking and put pressure on companies using rosewood from Madagascar.

Coup leaders sell out Madagascar’s forests, people

(01/27/2010) Madagascar is renowned for its biological richness. Located off the eastern coast of southern Africa and slightly larger than California, the island has an eclectic collection of plants and animals, more than 80 percent of which are found nowhere else in the world. But Madagascar’s biological bounty has been under siege for nearly a year in the aftermath of a political crisis which saw its president chased into exile at gunpoint; a collapse in its civil service, including its park management system; and evaporation of donor funds which provide half the government’s annual budget. In the absence of governance, organized gangs ransacked the island’s biological treasures, including precious hardwoods and endangered lemurs from protected rainforests, and frightened away tourists, who provide a critical economic incentive for conservation. Now, as the coup leaders take an increasingly active role in the plunder as a means to finance an upcoming election they hope will legitimize their power grab, the question becomes whether Madagascar’s once highly regarded conservation system can be restored and maintained.

World Bank, European governments finance illegal timber exports from Madagascar

(01/11/2010) While Madagascar’s current government has drawn sharp criticism from the international community for its failure to prevent the environmental destruction of recent months, France, Holland, Morocco, and the World Bank have all been implicated in financing illegal logging operations in Madagascar’s national parks over the past year. Even as foreign governments condemned the surge in illegal logging last year, many–either directly or through institutions they support–are shareholders in the very banks that have financed the export of illegal lumber from Madagascar’s SAVA region. The Bank of Africa Madagascar, for instance, is part owned by Proparco, a subsidiary of the Agence Française du Développement, as well as the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, Dutch development bank FMO, and the Banque Marocaine du Commerce Extérieur. Société Générale and Crédit Lyonnais, both part-owned by the French government, have also provided loans to illegal timber traders.

(12/16/2009) In the midst of cyclone season, a ‘dead’ period for tourism to Madagascar’s east coast, Vohémar, a sleepy town dominated by the vanilla trade, is abuzz. Vanilla prices have scarcely been lower, but the hotels are full and the port is busy. “This afternoon, it was like a 4 wheel drive show in front of the Direction Regionale des Eaux & Forets,” one source wrote in an email on November 29th: “Many new 4×4, latest model, new plane at the airport, Chinese everywhere.”