A rainforest tribe fighting to save their territory from loggers owns the carbon-trading rights to their land, according to a legal opinion released today by Baker & McKenzie, one of the world’s largest law firms.

The opinion, which was commissioned by Forest Trends, a Washington, D.C.-based forest conservation group, could boost the efforts of indigenous groups seeking compensation for preserving forest on their lands, effectively paving the way for large-scale indigenous-led conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Indigenous people control more than a quarter of the Brazilian Amazon.

“This really is a landmark opinion,” said Michael Jenkins, President and CEO of Forest Trends. “What we have been able to demonstrate here is that there will be opportunity and a path forward for indigenous groups to participate in emerging markets from a global warming deal. In fact, the indigenous groups would now be part of the solution.”

Baker & McKenzie reached its conclusion based on the Brazilian Constitution and legislation, which “provides for a unique proprietary regime over the Brazilian Indians land… which reserves to the Brazilian Indians… the exclusive use and sustainable administration of the demarcated lands as well as… the economic benefits that this sustainable use can generate.”

|

While the legal opinion was commissioned on behalf of the Surui tribe in Rondonia, Brazil, it should apply across Brazil and could set a precedent in other countries as well.

“This finding should greatly help the Surui and, by extension, other indigenous groups in Brazil,” said Beto Borges, Director of Communities and Markets Programs at Forest Trends. “Not only do the indigenous groups have the ethical right for carbon credits projects on their land and because of their stewardship role over the generations, but this finding now means they have the legal right as well. It’s a major step forward.”

Securing forest-carbon rights to their land would allow the Surui to win compensation for their efforts to protect their forest home. The tribe has long battled development interests and is counting on payments from carbon conservation to help finance its 50-year sustainable development plan.

“This study confirms that we have the right to carbon, and is also an important political and legal instrument to recognize the rights of indigenous people for the carbon in their standing forests,” said Chief Almir Narayamoga Surui, leader of the Surui tribe. “It helps in our dialog with the government, businesses, and other sectors, strengthening the autonomy of indigenous peoples to manage our territories.”

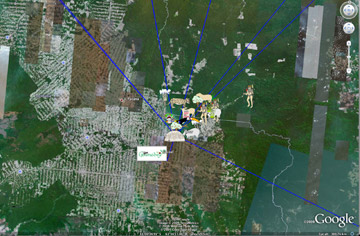

Interactive Google Earth layer about the Surui tribe |

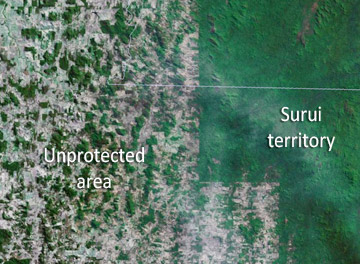

Recent research has shown that indigenous reserves are particularly effective at slowing forest clearing in high-deforestation frontier regions. A study by researchers at the Woods Hole Research Center and the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazonia found that the incidence of fire and deforestation within indigenous reserves was half that of surrounding unprotected areas. But this very stewardship has raised fears among some that indigenous groups would miss out on forest carbon payments since these schemes typically reward activities that reduce forest clearing relative to a baseline of past deforestation.

“REDD should enhance recognition that indigenous people have maintained the state of their forests, not penalize them for this stewardship,” Vasco van Roosmalen, director of the Amazon Conservation Team-Brazil, an NGO that has helped the Surui develop ethnographic maps of their lands, told mongabay. “Indigenous lands are the most important barrier to Amazon forest clearing”

Related articles

(11/29/2009) A new handbook lays out the methodology for cultural mapping, providing indigenous groups with a powerful tool for defending their land and culture, while enabling them to benefit from some 21st century advancements. Cultural mapping may also facilitate indigenous efforts to win recognition and compensation under a proposed scheme to mitigate climate change through forest conservation. The scheme—known as REDD for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation—will be a central topic of discussion at next month’s climate talks in Copenhagen, but concerns remain that it could fail to deliver benefits to forest dwellers.

Google partners with Amazon tribe

(10/29/2009) The story of an indigenous Amazon tribe that has embraced technology in its fight to protect its homeland and culture is now highlighted as a layer in Google Earth.

(07/08/2009) Until forty years ago, the Surui people spent their days roaming the Brazilian Amazon with bows and arrows, hunting monkeys and wild pigs. Their only contact with the outside world was with the rubber tappers who occasionally ventured through their territory. Then, beginning in the late 1960s, the Brazilian government laid a 2,000-mile highway through the heart of the jungle. Lured by the promise of cheap, fertile land, thousands of poor farmers boarded buses, rickety pickups, and horse-drawn wagons and bore deep into Surui tribal lands. The results were catastrophic. First the tribe was decimated by disease. Then unscrupulous speculators started hawking fraudulent titles to the land, spawning bloody turf wars between the tribe and settlers. Within a few years, the Surui population dwindled from roughly 2,000 to fewer than 200. Amid the onslaught, neighboring tribes scattered, died off, or sold out to loggers and ranchers. But the bitter suffering and long odds only seemed to sharpen the Suruis’ resolve and fighting instincts. After ten years of struggle, in 1982, the tribe rose up, armed with clubs and poison arrows, and drove the settlers from their land. Since then, the Surui have been battling to keep new incursions at bay. The tribe has split into four groups, each living in a different corner of their 600,000-acre territory, so they can better guard their turf. They regularly throw chains over logging roads, chase miners out of pits and rivers, and take the government to task for failing to rein in the destruction. So far, their tenacity has paid off: even as development has eaten away at the surrounding landscape, the tribe has managed to preserve their forests and their way of life. Viewed by satellite, their territory is a lone patch of green amid stretches of barren, ocher earth. But the struggle is relentless. In the last decade, the Surui and neighboring tribes have seen eleven tribal elders assassinated. At one point their chief, Almir Surui, was evacuated by helicopter to the United States because of threats to his life.

Satellites and Google Earth prove potent conservation tool

|

(03/26/2009) Armed with detailed images from space and remote sensing data, scientists, environmentalists, and armchair conservationists are now tracking threats to the planet and communicating them vividly to the public. Posted on the e360, an online publication from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies

How to save the Amazon rainforest

(01/04/2009) Environmentalists have long voiced concern over the vanishing Amazon rainforest, but they haven’t been particularly effective at slowing forest loss. In fact, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars in donor funds that have flowed into the region since 2000 and the establishment of more than 100 million hectares of protected areas since 2002, average annual deforestation rates have increased since the 1990s, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 square miles) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004. With land prices fast appreciating, cattle ranching and industrial soy farms expanding, and billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure projects in the works, development pressure on the Amazon is expected to accelerate. Given these trends, it is apparent that conservation efforts alone will not determine the fate of the Amazon or other rainforests. Some argue that market measures, which value forests for the ecosystem services they provide as well as reward developers for environmental performance, will be the key to saving the Amazon from large-scale destruction. In the end it may be the very markets currently driving deforestation that save forests.

Amazon Indians use Google Earth, GPS to protect forest home

|

(11/14/2006) Deep in the most remote jungles of South America, Amazon Indians are using Google Earth, Global Positioning System (GPS) mapping, and other technologies to protect their fast-dwindling home. Tribes in Suriname, Brazil, and Colombia are combining their traditional knowledge of the rainforest with Western technology to conserve forests and maintain ties to their history and cultural traditions, which include profound knowledge of the forest ecosystem and medicinal plants. Helping them is the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), a nonprofit organization working with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests.

Indians are key to rainforest conservation efforts says renowned ethnobotanist

|

(10/31/2006) Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans -medicine men and women – who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. The combined loss of this knowledge and these forests irreplaceably impoverishes the world of cultural and biological diversity. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author (Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice, Medicine Quest) who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Hero for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. Plotkin believes that existing conservation initiatives would be better-served by having more integration between indigenous populations and other forest preservation efforts.