U.S. biofuels policy drives deforestation in Indonesia, the Amazon

U.S. biofuels policy drives deforestation in Indonesia, the Amazon

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

January 17, 2008

U.S. incentives for biofuel production are promoting deforestation in southeast Asia and the Amazon by driving up crop prices and displacing energy feedstock production, say researchers.

William Laurance, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, says that massive subsidies to promote American corn production for ethanol have shifted soy production to Brazil where large areas of cerrado grasslands are being torn up for soybean farms. The expansion of soy in the region is contributing to deforestation in the Amazon.

“Some forests are directly cleared for soy farms. Farmers also purchase large expanses of cattle pasture for soy production, effectively pushing the ranchers further into the Amazonian frontier or onto lands unsuitable for soy production,” said Laurance.

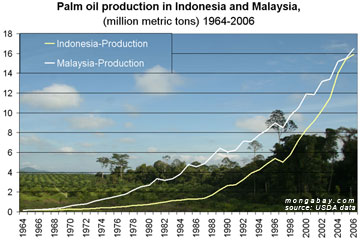

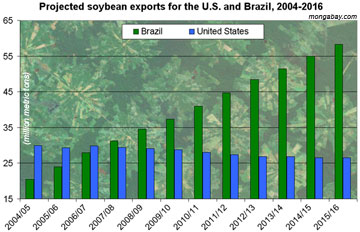

Projected soybean exports for Brazil and the United States, 2004-2015. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge. |

“In addition, higher soy costs tend to raise beef prices because soy-based livestock feeds become more expensive, creating an indirect incentive for forest conversion to pasture,” added Laurance. “Finally, the powerful Brazilian soy lobby has been a driving force behind initiatives to expand Amazonian highway networks, which greatly increase access to forests for ranchers, farmers, loggers, and land speculators.”

Satellite imagery from NASA supports Laurance. Data released last summer indicates that much of the recent burning is concentrated around two major Amazon roads: Trans-Amazon highway in the state of Amazonas, and the unpaved portion of the BR-163 Highway in the state of Pará.

Brazilian satellite data also show a marked increase in the number of fires and deforestation in the region. The states of Para and Mato Grosso — the heart of Brazil’s booming agricultural frontier — both experienced a 50 percent or more increase in forest loss over the same period last year coupled with a large jump in burning: a 39-85 percent jump in the number of fires in Para during the July-September burning period and 100-127 percent rise in Mato Grosso, depending on the satellite. More broadly, the 50,729 fires recorded by the Terra satellite and 72,329 measured by the AQUA satellite across the Brazilian Amazon are the highest on record based on available data going back to 2003.

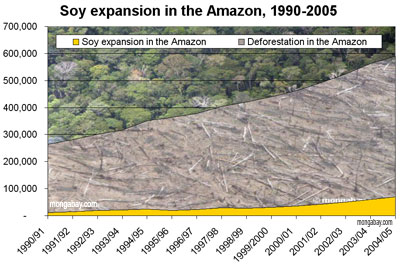

Total deforestation and area of soybean cultivation across states in the Brazilian Amazon. Overall soybean cultivation makes up only a small portion of deforestation, though its role is accelerating. Further, soybean expansion and the associated infrastructure development and farmer displacement is driving deforestation by other actors. Note: some soybean farms are established on already degraded rainforest lands and neighboring cerrado ecosystems. Therefore it would be inappropriate to assume the area of soybean planting represents its actual role in deforestation. |

“American taxpayers are spending $11 billion a year to subsidize corn producers—and this is having some surprising global consequences,” said Laurance. “Amazon fires and forest destruction have spiked over the last several months, especially in the main soy-producing states in Brazil. Just about everyone there attributes this to rising soy and beef prices.”

“We see soy prices going up partly because less soy is being grown in the U.S. as corn expands to meet the surging demand for the emerging ethanol industry,” explained Daniel Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center. “Soy production is… encroaching on the Amazon.”

Biodiesel trends conspire to destroy orangutan habitat in Indonesia

While the corn connection to deforestation in the Amazon has been well-explored in recent months, the American biodiesel incentives that are promoting soy expansion in the Amazon are also fueling oil palm establishment in Indonesia, by boosting prices for all energy crops.

Clay Ogg, an agricultural economist with the U.S. government, finds the current biofuel boom has lifted palm oil prices by nearly half, leading to oil palm plantation expansion in Indonesia and Malaysia at the expense of carbon-rich peat swamps and species-rich tropical rainforests.

“Reductions in U.S. exports of corn and other crops lead to higher, world commodity prices,” wrote Ogg in a paper presented last year at a Farm Foundation conference on “Biofuels, Food & Feed Tradeoffs” in St. Louis, Missouri. “Higher prices can contribute substantially to deforestation in tropical countries.”

“In the U.S., it is easy to plant less soybeans and more corn when the price of corn doubles, as occurred recently. This raises the world price of soybean oil… so we are a major contributor to the increase in vegetable oil and palm oil prices,” he continued.

“Palm oil is the cheapest to produce of the vegetable oils, so when European drivers burn rapeseed oil or soybean oil in their cars, it causes vegetable oil prices to increase, including palm oil prices. As various vegetable oils are used for fuel in Europe, in the U.S. and in other countries, China will meet its growing vegetable oil needs by importing palm oil, and palm oil prices are projected to increase by about 50 percent, largely as a result of the biofuel related demands. Consumption of various vegetable oils in automobiles, therefore, provides much the same encouragement to drain swamps in Indonesia as does the consumption of palm oil.”

The draining of peat swamps in Indonesia results in large carbon dioxide emissions — some 2 billion tons per year according to estimates by Wetlands International. These releases have made Indonesia the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases after the U.S. and China, despite the country’s small industrial base.

Clay Ogg’s paper is especially pertinent as India’s Tata Motors rolls out its Nano, a $2500 car that is projected to expand the Indian car market by 65% according to rating agency CRISIL, creating more demand for fuels, including biodiesel.

“The Nano and similar hyper-affordable models currently under development by other manufacturers could expand oil demand much faster than expected,” states an editorial from Biopact, a bioenergy web site. “A scenario based on a very rapid expansion of the global car fleet and its effects on oil prices could have one immediate result: a massive and unstoppable rush into biofuels. Because the poor not only want to own their Nano, they want to drive it. Ultra-expensive gasoline simply won’t be an option… For the millions of new small car owners, biofuels – even with all their current drawbacks – would become the only acceptable alternative to unaffordable gasoline.”

Although the U.S. is unlikely to see much of a jump in car ownership or fuel consumption as fleet-wide vehicle fuel efficiency improves in response to higher gas prices and new laws, its subsidies may impact palm oil biodiesel consumption in other ways, says Dorab Mistry, an analyst of London-based Godrej International Ltd, a research firm.

“The subsidy the U.S. government gives is meant to encourage local soybean oil being converted into biofuel. But many people are importing palm diesel instead of using local soyoil to make biofuels,” Dorab Mistry told Reuters. “They import palm diesel, mix it with 1 percent local diesel, make the blend, that is biofuel, and collect the subsidy.”

Though this source of demand for palm oil is small, the overall impact of U.S. policy on biofuels is substantial.

Will the U.S. follow in Europe’s footsteps? Not likely

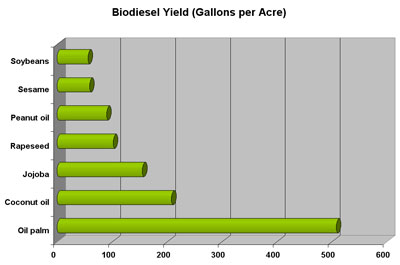

Biodiesel yield for various crops

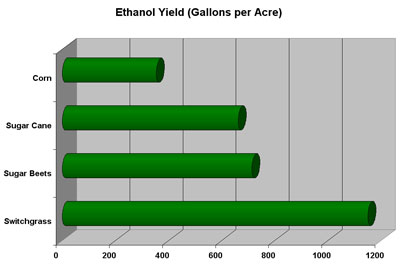

Ethanol yield for various crops

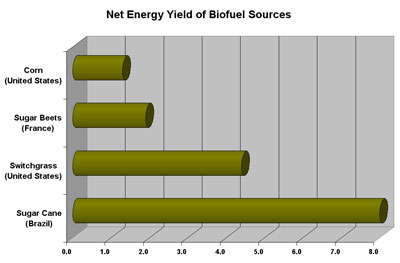

Ney energy yield for various crops |

While it is clear that U.S. incentives for biofuel production are having a substantial environmental impact beyond American borders, it is unlikely that the country will take steps to mitigate damages from these supposedly “green” energy sources. The U.S. farm lobby continues to demand generous subsidies for corn ethanol production, while a tariff on imported ethanol “protects” American consumers from savings that would otherwise be realized from biofuels produced more-efficiently overseas. Further, because the U.S. imports little biodiesel directly, it means that initiatives like that announced by the E.U. this week — which bans biofuels produced on forest lands and in other sensitive ecosystems — won’t have much of an impact.

The best hope for mitigating the damages wrought by U.S. bioenergy policy may lie in the next generation of biofuels, specifically feed stocks derived from farm waste, weedy grasses (switchgrass, miscanthus), and fast-growing trees (poplar, sweet gum). Researchers say such “second generation” biofuels offer a higher net energy balance with lower greenhouse gas emissions. Further, such feed stocks can be grown with fewer fertilizer and pesticides, and are viable on marginal agricultural lands so they don’t compete with food crops.

References

- Ogg, C. (2007) Environmental Challenges Associated with Corn Ethanol Production. Presented at the Farm Foundation conference on “Biofuels, Food & Feed Tradeoffs” in St. Louis, Missouri, on April 12, 2007

- Jan Fuglestvedt et al. (2007). Climate forcing from the transport sectors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences January 7-11, 2008.

- Laurance, W. F. Science 318, 1721 (2007)

- Other citations linked in the text