- Many tropical forests around the world have been severely fragmented as human disturbance split once-contiguous forests into pieces. Previous research indicates trees on the edges of these fragments have higher mortality rates than trees growing in the interiors of forests.

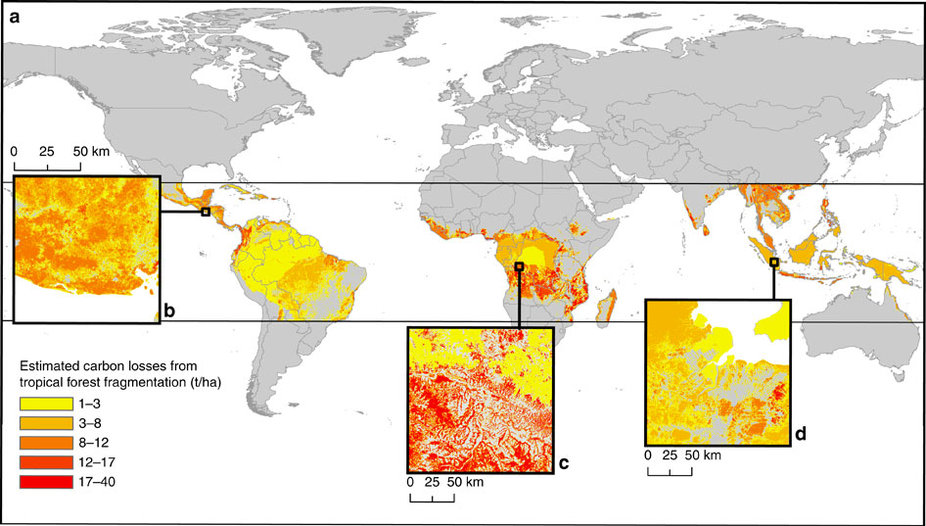

- Researchers used satellite data and analysis software they developed to figure out how many forest fragments there are, and the extent of their edges. They discovered that there are around 50 million tropical forest fragments in the world today; their edges add up to about 50 million kilometers – about a third of the way from the earth to the sun.

- When they calculated how much carbon is being released from tree death at these edges, they found a 31 percent increase from current tropical deforestation estimates.

The earth’s forests have been broken into around 50 million fragments, the edges of which add up to a length that would make it a third of the way to the sun and which increase annual tropical deforestation carbon emissions by 31 percent. This, according to a new study published recently in Nature Communications that reveals forest fragmentation may be much more destructive than previously thought.

A few hundred years ago, most large tropical forests stood vast and largely undisturbed. But since then, agriculture and extractive industries have moved in, whittling away forests to make room for cattle pasture and soy fields, palm oil plantations and acacia concessions.

Today, owing primarily to human pressures, many of the world’s tropical forests exist as a collection of remnants. The Atlantic Forest is one of these. Once covering a huge swath of the eastern coast of Brazil and into Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina, the Atlantic Forest (called Mata Atlântica in Portuguese) has largely disappeared, and some researchers estimate just 3.5 percent may still remain – mostly as fragments interspersed in an expanse of pasture and cropland.

Research has shown that forest fragmentation can have dire effects on wildlife, leading to higher extinction rates than if a forest is simply reduced in size while remaining in one piece. But how fragmentation affects carbon emissions is something that scientists haven’t been able to grasp – until now.

Enter researchers with the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research and the University of Maryland. They drew on previous studies that showed tree mortality in tropical forests was affected significantly by where they trees were, with trees on the edges of forests having double the chances of dying in a given year. This is because vegetation at edges is exposed to harsher conditions like stronger wind, more intense solar radiation, and lower humidity than trees in the interior of forests. The research showed that this wasn’t only affecting periphery trees, but also tree as far as a hundred meters into forests.

“Large trees suffer most from this development, because they are reliant on a good supply of water,” said Andreas Huth of the Hemholtz Center, coauthor of the study released this week.

But how much is this fragmentation edge effect contributing to carbon emissions and, thus, global warming? To find out, Huth and his colleagues developed their own software to analyze satellite data and determine just how many forest edges human disturbance has created.

Turns out, it’s a lot – around 50 million kilometers of edges for as many fragments. Placed end-to-end, these forest edges would make it about a third of the way from the earth to the sun. According to the study’s findings, 19 percent of the world’s tropical forests are currently 100 meters (328 feet) or less from a forest edge.

Current estimates peg the volume of carbon emissions from the clearing of tropical forests at around 1,100 million metric tons annually. Using field data and computer modeling, the team calculated 340 million more metric tons of carbon may be released globally due to forest edge effects. In other words, the study finds forest fragmentation may be contributing 31 percent more carbon to the atmosphere than previous estimates are accounting for.

“Fragmentation therefore plays an important role in the global carbon cycle,” Huth said. “Despite this fact, this effect has not been taken into consideration at all in the IPCC reports to date.”

The IPCC to which Huth is referring is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the international body responsible for assessing science related to climate change. The IPCC’s findings provide the scientific scaffolds that inform policymakers and underlie the negotiations at the UN Climate Conference – the United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC). One component of the UNFCCC is REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation), a program that aims to keep tropical forests in the ground – and, thus, carbon out of the atmosphere – by providing financial incentives to the developing countries that contain them.

The researchers hope the influence of forest fragmentation on carbon emissions will be taken into account when it comes to climate change policies and programs.

“Our analyses show that forest fragmentation augments carbon emissions beyond those caused by deforestation,” they write in their study. “Although we expect that our study bases on conservative assumptions, they are already substantial enough to highlight the importance of forest fragmentation in the global carbon balance.”

Citations:

Brinck, K., Fischer, R., Groeneveld, J., Lehmann, S., De Paula, M. D., Pütz, S., … & Huth, A. (2017). High resolution analysis of tropical forest fragmentation and its impact on the global carbon cycle. Nature Communications, 8, 14855.

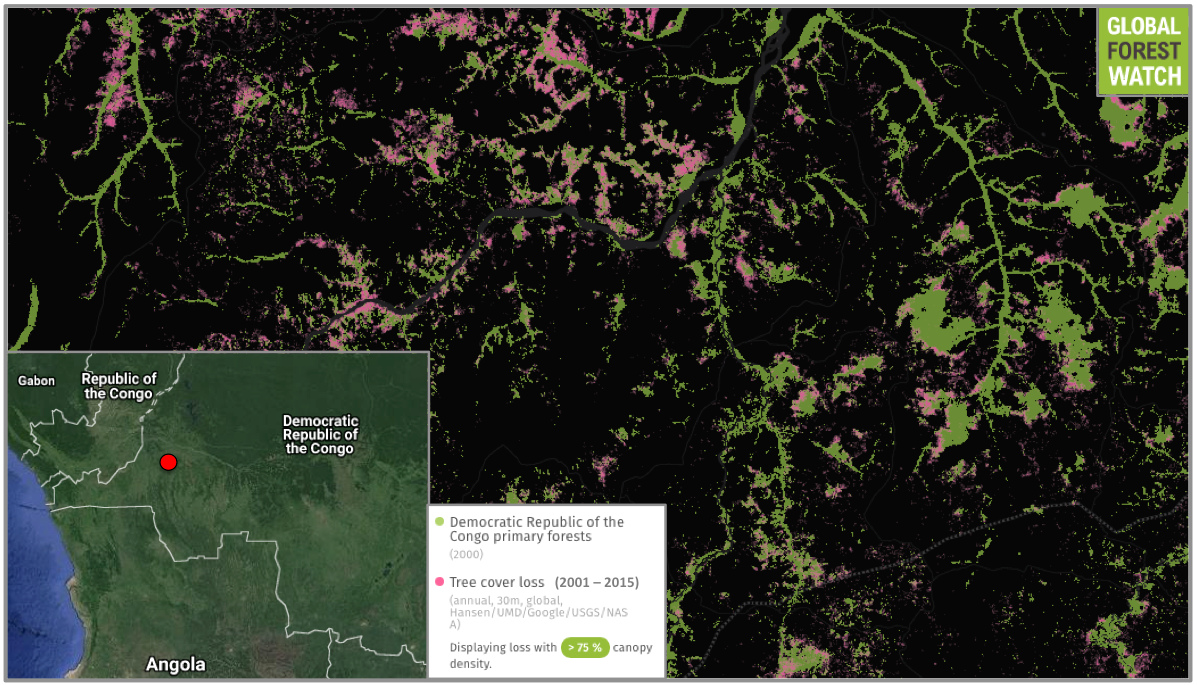

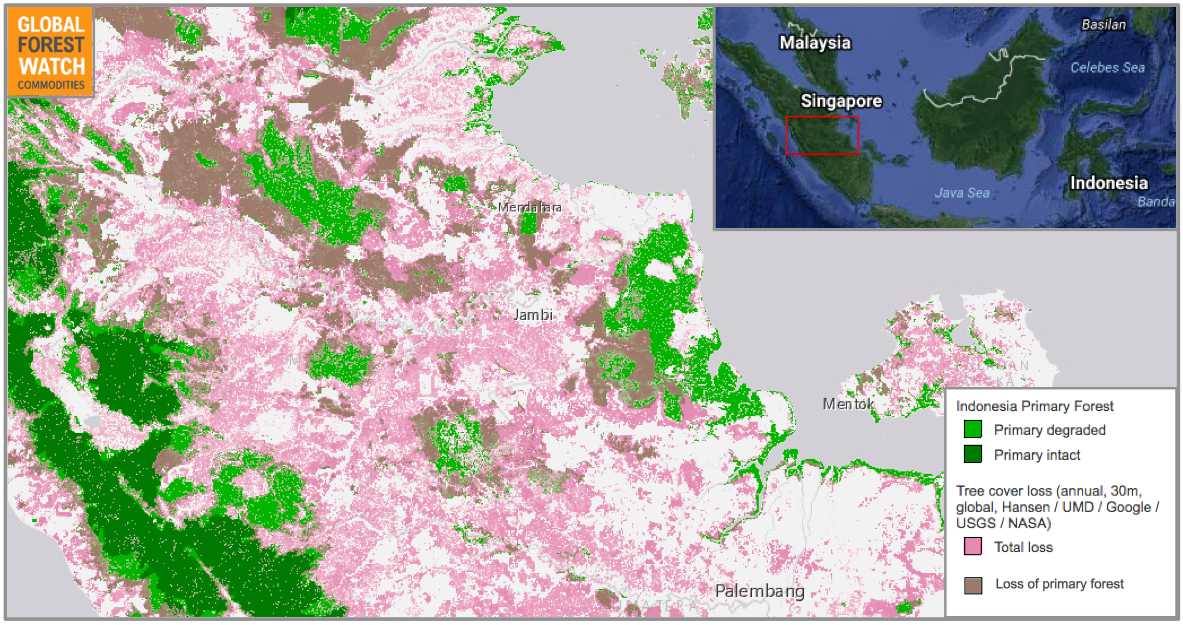

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from:http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 31, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Margono, B.A., P.V. Potapov, S. Turubanova, F. Stolle, and M.C. Hansen. “Indonesia primary forest.” Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 31, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Observatoire Satellital des forêts d’Afrique centrale, South Dakota State University, and University of Maryland. “Democratic Republic of the Congo primary forests”. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 31, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.