From massive hotel development through the agriculture industry, humans are destroying the second largest barrier reef in the world: the Mesoamerican Reef. Although global climate change and its effects on reefs via warming and acidification of coastal waters have made recent headlines, local human activities may destroy certain ecosystems before climate change has a chance to do it. The harmful effects of mining, agriculture, commercial development, and fishing in coastal regions have already damaged more than two-thirds of reefs across the Caribbean, in addition to worsening the negative effects of climate change.

A recent evaluation by the Healthy Reefs Initiative (HRI, www.healthyreefs.org) of the Mesoamerican Reef (MAR), which runs continuously for over 1,000 km, from north of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula south to Honduras, highlights the combination of locally-grown threats to this iconic ecosystem.

Figure 1. The Mesoamerican Reef with 193 sites coded by their Simplified Integrated Reef Health Index (SIRHI) score. Orange and red sites have poor or critically poor reef health. Map from Healthy Reefs Initiative.

Coral reefs: valuable yet complex systems

Coral reefs are unique ecosystems, which provide human communities with a suite of irreplaceable benefits. They feed millions of people worldwide, buffer harbors and shorelines from storm waves, restock fisheries by sheltering juvenile fish, and attract snorkeling and SCUBA-diving tourists to coastal regions. They even supply much of the sand seen on the region’s beaches. In the Caribbean, reefs are also a key source of income: tourism is the major employer in the coastal zone around the Mesoamerican Reef. According to HRI, tourism employs a third of working adults in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, centered around Cancun, and contributes nearly a quarter of overall GDP in Belize.

The Mesoamerican Reef ecosystem encompasses barrier, fringe, patch, and atoll coral reefs, as well as adjacent mangroves, lagoons, and seagrass beds and the amazing variety of plant and animal species living within these different formations. To attempt to measure and monitor the health of an ecosystem as complex as a coral reef, the HRI publishes a Report Card for the Mesoamerican Reef using key indicators of reef health. For the 2012 Report Card, HRI and partners monitored 193 sites across the reef. HRI has developed a single index, their Simplified Integrated Reef Health Index (SIRHI), from a combination of four of the indicators – live coral cover, fleshy macroalgae cover, biomass (the number and size) of herbivorous (vegetarian) fish, and biomass of commercially valuable fish – that can be easily compared among sites and over time.

These indicators represent key elements for reef health: corals build the reef, and sufficient coral cover is needed to maintain reef structure. Macroalgae, a.k.a. seaweed, competes with corals on the reef, reduces coral growth, and simplifies reef habitat. Herbivorous fishes eat the macroalgae, which creates space for corals to recover, while levels of commercially important fishes indicate the intensity of fishing pressure and the intactness of the fish community.

Figure 2. Overall ranking of 193 reef sites in the Mesoamerican Reef system by their Simplified Integrated Reef Health Index (SIRHI) score. Only one site received a rank of Very Good, while 64% of the sites were considered in Poor or Critical condition |

Land-based local threats

Ironically, some of the worst threats to coral reefs are caused by human activities on land. The conversion of natural vegetation to agriculture or commercial development, together with modern agricultural methods and waste disposal, have jeopardized the ability of watersheds in the western Caribbean to maintain water quality. Water full of sediment, industrial pollutants, agricultural chemicals, and high concentrations of nutrients that runs into the sea changes the chemistry of the reef environment, making reef ecosystems more susceptible to diseases that kill corals and other organisms.

How do these activities affect coral reefs?

Coral polyps (the individual organisms that join to form the reef) depend on energy produced through photosynthesis by tiny single-celled plants, called zooxanthellae, that live within corals. Sediment that settles on a reef or in the water column above it covers up the zooxanthellae, preventing them from photosynthesizing. In waters with few nutrients, such as those around coral reefs, the energy produced by the zooxanthellae inside the coral polyps gives coral a competitive advantage over organisms that must produce their own energy. However, when sewage and agricultural runoff containing loads of nitrogen and phosphorous enter the sea, the tables are turned. The influx of these nutrients encourages the growth of macroalgae, which allows them to outcompete living coral for space on the reef. In addition, chemicals in pesticides, industrial pollutants, and urban runoff, as well as fuel and waste leaked from ships and oil platforms, can kill or damage corals.

Pervasive sea-based threats

Caribbean reefs confronting these modern-day disturbances also suffer from damaged fish communities caused by a history of overfishing and predation from an aggressive invasive fish species. Overfishing, which affects over 60% of Caribbean reefs, not only reduces fish populations but also worsens the effects of pollution and sedimentation. Fishers target the larger species, often the reef’s top predators, such as sharks and groupers, that regulate populations of smaller fish. Fishers also deplete populations of large herbivorous fishes, such as parrotfish, that eat the macroalgae and keep it from spreading. For example, when disease caused a huge die-off of a sea urchin called Diadema antillarum in 1983, a key macroalgae grazer across the Caribbean, the numbers of other macroalgae-eating fish on reefs at the time were too low to control algal growth. With too few consumers, the macroalgae began to spread across large portions of reefs, changing the coral-algae balance.

More recently, the poisonous Indo-Pacific lionfish, first recorded in the Mesoamerican Reef in 2008 but now found in both Caribbean and mid-Atlantic waters, has begun to devastate the region’s native fish communities. Lionfish eat most fish smaller than they are, and they have slashed the numbers of small native fish and invertebrates by up to 95% on some reefs. Lionfish also reproduce rapidly and grow larger in the Caribbean than in their native environments, making them an increasingly serious threat to entire fish communities.

Downward trends but variable damage

Fifty reef sites (36 in Belize, 4 in Honduras and 10 in Mexico) were evaluated in all three Report Cards (2008, 2010 and 2012), and the proportion of these sites in different conditions can be tracked over time. |

The combined impacts of nutrient overloading and the loss of algae-eating fish have reduced live coral cover not only in the Mesoamerican Reef but across the Caribbean. In the last 40 years, coral cover has shrunk from roughly 50% to 10-15% in Caribbean reefs. The replacement of coral with algae simplifies the reef’s structure and decreases its ability to both sustain other species and provide benefits to humans.

According to the HRI report, a reef with a “good” coral cover ranking has at least 20% live coral covering its surface, and “good” macroalgae cover is 5% or less. Of the 193 sites ranked by HRI, 63 (32%) have at least 20% live coral cover. Another 81 sites retain at least 10% coral cover, the proportion required by reefs to produce enough carbonate to continue to grow. The remaining 25% of sampled reef sites already lack even the 10% coral cover needed to enable further growth, which suggests that the Mesoamerican Reef will grow only minimally in the near future. Only one site, the offshore Banco Chinchorro in Mexico, still has the recommended < 5% cover of macroalgae. On 135 sites (70%), macroalgae covers over 12% of the reef, which represents a “poor” or “critical” condition.

Scores for herbivorous and commercial fish indicators suggest that the region’s fish populations are in danger as well: 78% of the reef sites have “poor” or “critical” scores for commercial fish, and 58% of the sites have similarly low levels of herbivorous fish. Even on reefs fringing offshore islands, the researchers found surprisingly low herbivorous fish populations, suggesting more intensive fishing there than expected. These low populations of algae-eating fish may be contributing to the relatively high levels of macroalgae cover, even on these outer reefs.

According to Dr. Lorenzo Álvarez Filip, Scientific Coordinator for HRI and a diver who has studied the Mesoamerican Reef for nearly 15 years, the overall condition of coral reefs in the Caribbean has deteriorated over the course of his career, but locations varied in both their current status and the change in their condition.

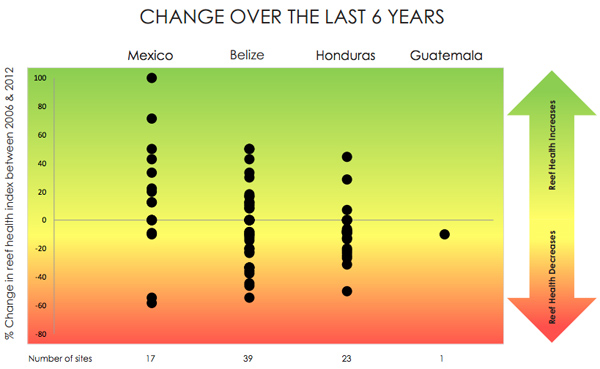

Figure 3. This graphic, from the HRI 2012 Report Card for the Mesoamerican Reef, shows changes in the SIRHI score, representing reef health, at 80 sites monitored in 2005-2006 and again in 2011-2012. Each dot represents a site. Distance from the horizontal line signifies the amount of positive or negative change in reef health between those time periods. An increase from “critical” to “poor” quality was considered an improvement, while a decrease from “very good” to “good” signified a decline in health. Reef health increased at 26 sites (above the line), remained stable at 14, and decreased at 40 sites (below the line).

The importance and impact of local solutions

Overfishing, pollution, sedimentation, and decline in watershed vegetation can all exacerbate the loss of corals caused by ocean acidification resulting from higher amounts of carbon dioxide in seawater, and bleaching associated with warmer water that causes the tiny, yet vital, zooxanthellae to leave corals. Actions that reduce local human pressures are essential to helping coral reef systems become more resilient to these two broad effects of climate change. Stronger reefs, in turn, provide greater support to both animal and human communities.

In parts of the Mesoamerican Reef, some of the key indicators have improved, due to fewer damaging storms in recent years and some preventative measures taken by communities. In 2009, the Belizean government gave full protection to algae-eating parrotfish and surgeonfish. A greater abundance of these fish measured on the Belize reef sites since the regulation suggest the policy may be helping the fish recover. In 2011, Belize also banned bottom trawling, a destructive shrimp harvesting practice. At a more local scale, fishing cooperatives in Mexico and Guatemala have established the first fish refuges, or “no-take zones,” in their respective regions. In Mexico, the effort involves more than 40 organizations, including several governmental agencies, with an aim to create a network of no-take zones. By allowing fish to grow, disperse, and reproduce, no-take zones stimulate recovery of fish populations both inside and outside the refuge area, and they have become increasingly common in the Caribbean.

Coral reef and clouds off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. |

The HRI 2012 Report Card (found here: http://www.healthyreefs.org/cms/report-cards/) makes a series of recommendations for public and private institutions, including protecting natural vegetation in watersheds, creating coastal zone management plans, regulating specific fisheries, and using media more effectively to communicate research findings to local communities, policymakers, and resource managers .

The report also suggests some concrete actions that individual readers can take to help reefs. They can help lower pollution on reefs by conserving water and electricity, disposing of used fishing line and other litter on land, selecting renewable over disposable containers, and using ecofriendly cleaners. They can also help fish communities by abiding by fishing regulations and avoiding shark fin and other prohibited marine products.

“The Mesoamerican Reef, and reefs globally, are seriously threatened. Reef resources and services are essential components of the region’s social and economic welfare; preserving them requires a dedicated commitment from governments, non-governmental organizations, academia and the private sector,” writes Álvarez Filip. “In the [HRI] report, we present evidence that some reefs have been able to recover in recent years; however, this does not mean that they have returned to their optimum levels, so we still have a lot of work to do.”

CITATIONS:

- Álvarez-Filip, L., Dulvy, N.K., Gill, J.A., Côté, I.M., & Watkinson, A.R. 2009. Flattening of Caribbean coral reefs: region-wide declines in

architectural complexity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276(1669), 3019-3025. - Arkema, K.K., Guannel, G., Verutes, G., Wood, S.A., Guerry, A., Ruckelshaus, M., Kareiva, P., Lacayo, M. & Silver, J.M. 2013. Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nature Climate Change.doi:10.1038/nclimate1944.

- Burke, L. and J. Maidens. 2004. Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean. World Resources Institute. Washington, DC.

- Côté, I.M., Green, S.J. & Hixon, M.A. 2013. Predatory fish invaders: Insights from Indo-Pacific lionfish in the western Atlantic and Caribbean. Biological Conservation 164: 50–61.

- Darling, E.S., Green, S.J., O’Leary, J.K., & Côté, I.M., 2011. Indo-Pacific lionfish are larger and more abundant on invaded reefs: a comparison of

Kenyan and Bahamian lionfish populations. Biological Invasions 13(9): 2045-2051. - Gardner, T. A., Côté, I. M., Gill, J. A., Grant, A., & Watkinson, A. R. 2003. Long-term region wide declines in Caribbean coral reefs. Science 301:958-960.

- Hackerott, S., Valdivia, A., Green, S.J., Côté, I.M., Cox, C.E., et al. 2013. Native Predators Do Not Influence Invasion Success of Pacific Lionfish on Caribbean Reefs. PLoS ONE 8(7): e68259.

- Healthy Reefs for healthy people. 2012. Report Card for the Mesoamerican Reef. www.healthyreefs.org

- Jackson, J.B.C. 2001. What was natural in the coastal oceans? PNAS 98: 5411-5418.

- Maina, J., de Moel, H., Zinke, J., Madin, J., McClanahan, T., & Vermaat, J.E. 2013. Human deforestation outweighs future climate change impacts of

sedimentation on coral reefs. Nature Communications 4: 1986. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms2986. - Mora, C. 2008. A clear human footprint in the coral reefs of the Caribbean. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1636), 767-773.

- Perry, C.T., Murphy, G.N., Kench, P.S., Smithers, S.G., Edinger, E.N., Steneck, R.S., & Mumby, P.J. 2013. Caribbean-wide decline in carbonate production threatens coral reef growth. Nature communications, 4, 1402 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2409.

- Schutte, V.G.W., Selig, E.R., & Bruno, J.F. 2010. Regional spatio-temporal trends in Caribbean coral reef benthic communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 402:115-122.

- Sutherland, K.P., Shaban, S., Joyner, J.L., Porter, J.W., & Lipp, E.K. 2011. Human Pathogen Shown to Cause Disease in the Threatened Eklhorn Coral Acropora palmata. PLoS ONE 6(8): e23468. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023468

Related articles