An interview with Arbio

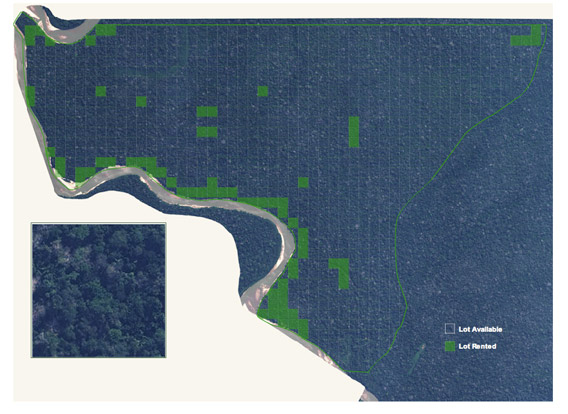

Left bank: Arbio’s concession area. Photo by: Arbio.

Arbio was begun by Michel Saini and Tatiana Espinosa Q. in the Peruvian Amazon region of Madre de Dios. The project focuses on a protective response to the increased encroachment and destructive land use driven by development. The recent construction of the Inter-Oceanic Highway in the Madre de Dios area presents an enormous threat to forest biodiversity. Arbio provides opportunities to help establish a buffer zone near the road to limit intrusive agricultural and deforestation activities.

Michel Saini is an Italian Environmental Engineer at the Polytechnic of Milan. In 2003 he traveled to Chile to study Forestry Engineering and learn what a real forest felt like. After this experience he decided to devote himself to the study and conservation of forests in Latin America. He moved to Costa Rica in 2007 and completed a Masters in Management and Conservation of Tropical Forests at CATIE, specializing in politics and governance of natural resources. In CATIE he meets a classmate, Tatiana Espinosa Q., Peruvian engineer in Forest Sciences at the UNALM, Peru. Her interest in the Amazon led her to work in the Madre de Dios region since 2003 on issues of Conservation, Wildlife and Management of non timber forest products. In 2009, after concluding the program, they traveled together to Madre de Dios and in 2010 Arbio was born. For more information, visit their website.

INTERVIEW WITH ARBIO

The Madre de Dios region is characterized by the world’s highest diversity of butterflies. There are over 1200 species. Photo by: Arbio.

Mongabay: What sorts of programs does Arbio plan to introduce in order to support local economies while avoiding the destruction of the forests and biodiversity in the Madre de Dios region?

Arbio: We plan to introduce the concept of productive conservation, which is a concept of coexistence of society with the rainforest ecosystem. Our project includes the introduction of the Analog Forestry method, which is the exact opposite of a monoculture: Is a culture with 20 or more species in the same hectare, with different height and age and nutritional requirements. Fertilizers are no longer necessary, when we find the correlations between the nutrients needed and produced by each culture. This method seeks to maintain a functioning ecosystem dominated by trees while providing non-timber products (Brazil nuts, medicinal plants, Amazon fruits, etc.) and maintain a wildlife habitat. In this way, we seek to empower rural communities socially and economically through the use of species that provide commercial products. This system is completely integrated with the landscape, emphasizing the biodiversity to ensure sustainable production and operation is based on ecological considerations and ecosystem restoration.

Mongabay: What are some of the most commonly seen animals in your area?

Arbio: Among the mammals we have the mighty jaguar (Panthera onca), tapir (Tapirus terrestris), “sajinos” or wild pigs (Pecari tajacu), hundreds of herds of peccaries (Tayassu peccary). In the river can be seen the capybara – the largest rodent in the world (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), deer (Mazama sp), nocturnal animals such a chozna (Potos flavus), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), and a variety of monkeys including the howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus), white-fronted capuchin (Cebus albifrons), night monkeys (Aotus sp.), and tamarins (Saguinus sp.).

Among the reptiles have the white caiman (Caiman crocodylus), the “taricaya” aquatic turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), tortoise (Geochelone denticulata), a variety of boas and snakes, lizards, etc.

Among the birds we have the second largest species of the macaw (Ara chloropterus), the largest stork in South America: the Jabiru (Jabiru mycteria), toucans (Ramphastos cuvieri), the most powerful bird of prey: the Harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), also egret (Egretta thula), guan (Mitu tuberosum), pucacunga (Penelope jacquacu).

In addition to a wide variety of arthropods such as butterflies (this region has the world record in butterfly species diversity), beetles, centipedes, spiders, ants that measure 4 cm, among others.

Mongabay: Could you describe Arbio’s system of land rental of forested area by the hectare for conservation and research purposes?

Arbio: Our project is funded entirely by individuals, through our web platform rentals. Any Internet user can choose their own hectare by seeing a satellite photo of each hectare of our base area and make a rental-for-conservation process which costs only US$42/year. Hectares chosen automatically come into the category of “absolute conservation” which means that only the local wildlife and our caretaker can enter, however, as the project progresses and the models of productive conservation will be implemented, we will connect by email the people who are protecting hectares in strategic locations (near the base camp or the trails) asking if they want to change their land’s use from absolute conservations to productive conservation. In short, the land use change possibility is only for strategic hectares and for those who want to give researchers the opportunity to test sustainable organic farming and/or medicinal plants following the model of the Analog Forestry, or to perform research related to the wildlife. Any details will be discussed with the tenant on a case by case basis. And if the tenant does not agree, the hectares will continue in absolute conservation, of course!

Mongabay: What are some of the major threats posed by the construction of the Inter-Oceanic Highway?

Concession area. Photo by: Arbio. |

Arbio: The threat is historical and well documented. The same Inter-Oceanic Highway, in the Brazilian soil, led to deforestation of 50 Km of each side of the road in 20 years after his construction. If we don’t do anything, the same thing will happen in our region too, only at a faster rate, because everything is growing and getting faster in this endless-growth way of life. The threat is the actual system of what is seen as “development.” Extensive monoculture just doesn’t work for society or for the ecosystem. Very few people can work in extensive agriculture and fewer people really benefit from the immense fields. Deforestation is everywhere and fires and smoke can be seen from kilometers away.

The Brazilian agro industry now can transport products directly to the Pacific coast avoiding a large trip from his Atlantic coast to the mayor markets: China and India. Additionally, the low price of land compared to Brazil, together with cost savings of Customs and the closer proximity to the Pacific will make the Peruvian Amazon the goal of the main industries of monocultures.

Mongabay: Are conservation initiatives such as Arbio able to out-compete competition by extractive industries such as gold mining and monoculture plantations in the tropics?

Arbio: The answer to this question relies on the education of the actual land-owner and their capacity of long-term thinking. The current land tenure system in the Peruvian Amazon, a system of concessions granted by the state, is actually helping our job, even if some laws are against sustainability. Having the concession of a land for 40 years, renewable and heritable allow the tenants to think in long-term solutions for support themselves and their families, and selling the land or deforesting for monoculture is an absolutely short-term solution. They know that most of people that have sold his land are now living in the peripheries of the capital without a way of living, and the people who have transformed they land to a monoculture are now paying banks and fertilizers suppliers, with little or no benefit to their way of life. We offer for free a way of living close to their ancestral traditions but embedded in the actual market and granting sustainability in the future, not only with the Analog Forestry method of culture but also with the insertion in the Fair Trade Market and the future Payment for Environmental Services, when this opportunity will be available. Long-term thinking is our way to gain actual way of development.

For more information, visit www.english.Arbioperu.org.

Satellite image of the Arbio base camp. Photo by: Arbio.

Brown capuchin (Cebus apella), observed in social groups of 6 to 18 individuals. Photo by: Arbio.

Cabana built with materials from the forest at the base camps. Photo by: Arbio.

Related articles

Tourism for biodiversity in Tambopata

(02/27/2012) Research and exploration in the Neotropics are extraordinary, life-changing experiences. In the past two decades, a new generation of collaborative projects has emerged throughout Central and South America to provide access to tropical biodiversity. Scientists, local naturalists, guides, students and travelers now have the chance to mingle and share knowledge. Fusion programs offering immersion in tropical biology, travel, ecological field work, and adventure often support local wilderness preservation, inspire and educate visitors.

New rainforest and indigenous reserve established in Peru

(02/07/2012) On February 4th, the Peruvian government and a small indigenous group created a new Amazon reserve, dubbed the Maijuna Reserve. Located in northeastern Peru, the 390,000 hectare (970,000 acres) reserve is larger than California’s Yosemite National Park and over three times the size of Hong Kong.

Majority of Andes’ biodiversity hotspots remain unprotected

(02/01/2012) Around 80 percent of the Andes’ most biodiverse and important ecosystems are unprotected according to a new paper published in the open-access journal BMC Ecology. Looking at a broad range of ecosystems across the Andes in Peru and Bolivia, the study found that 226 endemic species, those found no-where else, were afforded no protection whatsoever. Yet time is running out, as Andean ecosystems are undergoing incredible strain: a combination of climate change and habitat destruction may be pushing many species into ever-shrinking pockets of habitat until they literally have no-where to go.

Group releases close-up photos of ‘uncontacted’ tribe in Peru

(02/01/2012) New photos provide visual evidence of just how close the long-isolated tribe of Mashco-Piro people in the Amazon rainforest are to being contacted by the outside world—a perilous moment for tribes highly susceptible to disease and likely to defend their people and territory with weapons. According to indigenous rights NGO Survival International, the Maschco-Piro tribe has been seen more frequently outside of their forest home in Manu National Park in recent years. Some experts blame illegal logging in the park and helicopters used in oil and gas projects for the sightings.

Saving the world’s biggest river otter

(01/30/2012) Charismatic, vocal, unpredictable, domestic, and playful are all adjectives that aptly describe the giant river otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), one of the Amazon’s most spectacular big mammals. As its name suggest, this otter is the longest member of the weasel family: from tip of the nose to tail’s end the otter can measure 6 feet (1.8 meters) long. Living in closely-knit family groups, sporting a complex range of behavior, and displaying almost human-like capricious moods, the giant river otter has captured a number of researchers and conservationists’ hearts, including Dutch conservationist Jessica Groenendijk.