Saving fish for the developing world: small-scale fisheries “best hope” for sustainability

An Interview with Jennifer Jacquet:

Small-scale fisheries are “best hope” for sustainability in developing world

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

September 8, 2008

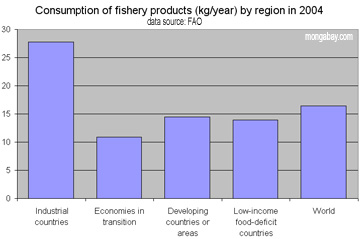

Fish stocks are declining globally. While the consumer in the industrial world has yet to feel the full impact of this decline, those in the developing world know it well. Local small-scale fishermen are catching less fish to feed growing populations. Jennifer Jacquet of the Sea Around Us Project believes the hope for sustainable seafood lies in these very fisheries.

“Small-scale fisheries…discard almost no fish, turn no fish into fishmeal, and use less fuel,” Jacquet told Mongabay.com in an interview describing the benefits of supporting small-scale fisheries. She adds that they “also provide more jobs than the industrial sector. Worldwide, the small-scale fishery sector provides work to more than 12 million people while the industrial sector employs only half a million.”

Jacquet explains that when the industrial fisheries of wealthy nations depleted their coastal waters of fish they moved out to “the last remaining bountiful fishing grounds, including tropical waters and the deep sea”. In the process marine waters that have provided a protein-rich food source to developing nations are suddenly under siege.

Jacquet holding a sunflower seastar in Puget Sound |

“These industrial fisheries can out-compete many coastal small-scale fisheries for the same fish. But, rather than feeding local people who rely on fish for survival, the seafood is shipped to food-secure markets in the U.S., Europe, and Japan,” Jacquet says.

Contributing to the problem, according to Jacquet, are global subsidies. Currently industrial fishing receives the majority of $30 billion dollars in subsidies handed out annually around the world for the seafood trade. There is a simple reason for this according to Jacquet: “industrial fishing boat owners have access to politicians”.

The subsidies have distorted the global seafood market wherein consumers in the industrial world do not pay the full cost of the fish they eat. This is keeping “seafood prices artificially low and demand high…right now the price of fish does not reflect the true scarcity”. Jacquet says fuel subsidies in particular “make it possible for these boats to go sea when it would otherwise be unprofitable”.

Jacquet, who has compared the situation to an anti-thesis of Robin Hood—the rich stealing from the poor—says that the issue can be argued on “moral grounds” especially where small-scale fisheries and industrial fisheries compete directly for the same catch.

Jacquet standing on a crater on the Galapagos Island of Santa Cruz. |

Jacquet believes that the solution to the problem is clear: “if we stop fishing, fish will recover.” She explains that “there is simply too much fishing effort and too little of the ocean is protected. Less than 1 percent of the ocean is closed to fishing! Compare this to the 12 percent of the terrestrial environment that is under protection. We need less fishing effort and more marine reserves. And we need them fast.”

As for consumers in the developed world, Jacquet does not believe it is enough to simply purchase sustainably caught fish. “I believe the public must engage primarily in the democratic process and activism… and disapproval of certain fish products must be expressed vertically up the supply chain (to chefs, store managers, and seafood suppliers) rather than simply laterally (consumer-to-consumer reproach).”

In the following August 2008 interview, Jennifer Jacquet answers questions about the plight of small-scale subsistence fisheries along with her work on the popular science blog, ‘Shifting Baselines’.

Mongabay: What is your field of study?

Jennifer Jacquet: I study marine science with a focus on fisheries and seafood markets.

Jacquet snorkeling near manatees in Crystal River, Florida |

Mongabay: What sparked your interest in becoming a marine biologist?

Jennifer Jacquet: I always had a deep affinity for manatees and other marine mammals, but by the time I became a conservation scientist I realized that marine mammals had many champions while the world’s fish had few. So I chose to work to preserve the ocean’s charismatically disadvantaged wildlife.

Mongabay: What advice would you have for students interested in studying marine biology?

Jennifer Jacquet: The oceans are an endless source of wonder but they are also in trouble. Choose a topic to study that someone will pay attention to and that could make a difference.

Mongabay: What is you favorite place to visit?

Jennifer Jacquet: Whenever I am in the ocean I am reminded of why I chose the route I did. Seeing underwater worlds that have not been totally adulterated by humanity, such as the Mafia Island Marine Park in Tanzania, give me hope for the future and a reason to keep working.

INDUSTRIAL FISHING FOR THE WEALTHY VERSUS SUBSISTENCE FISHING

Mongabay: In a recent paper you argue that small-scale fisheries could help preserve ocean life, conserve resources, and employ more laborers. Why is this?

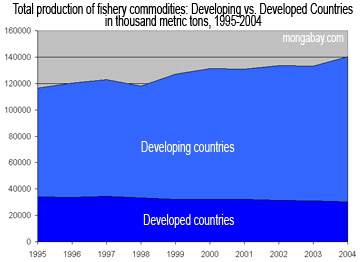

Total production of fishery commodities from 1995-2004: developing versus developed countries |

Jennifer Jacquet: Small-scale fisheries are our best hope at sustainable fisheries because they discard almost no fish, turn no fish into fishmeal, and use less fuel. They also use provide more jobs than the industrial sector. Worldwide, the small-scale fishery sector provides work to more than 12 million people while the industrial sector employs only half a million.

Mongabay: How does industrial fishing affect poverty in places such as East Africa and Oceania?

Jennifer Jacquet: The demand for seafood in the developed world coupled with overfishing of waters off most developed world nations has led to heavy industrial fishing fleets scouring the last remaining bountiful fishing grounds, including tropical waters and the deep sea. These industrial fisheries can out-compete many coastal small-scale fisheries for the same fish. But, rather than feeding local people who rely on fish for survival, the seafood is shipped to food-secure markets in the U.S., Europe, and Japan.

Mongabay: Recently you said, "This is the antithesis of the Robin Hood parable. Instead of stealing from the rich to give to the poor, we're stealing from the poor to give to the rich". Would you characterize the situation between industrial fishing and subsistence fishing as a moral one?

Jennifer Jacquet: To the extent that the small-scale fisheries and industrial fisheries compete for the same fish (which is not always), I certainly think you could characterize the situation as a moral one. One could argue on moral grounds that we should prioritize fish for those people who rely on them most. And it certainly is immoral to discard perfectly edible fish as many industrial fisheries, such as shrimp trawlers, do.

Jacquet with fisheries researchers on Mafia Island, Tanzania. |

Mongabay: Tell us the role that industrial fisheries' subsidies play in their dominance of the market?

Jennifer Jacquet: Industrial fisheries receive the vast majority of the approximately $30 billion in annual global fisheries subsidies. This is because industrial fishing boat owners have access to politicians. Many of these subsidies, such as fuel subsidies, make it possible for these boats to go sea when it would otherwise be unprofitable. This also helps keep seafood prices artificially low and demand high.

Mongabay: What should be done to make consumers aware of the actual costs—environmental and social—of the seafood they purchase?

Jennifer Jacquet: Certainly the elimination of harmful fisheries subsidies would mean that fish would become more expensive and demand would therefore decrease. Right now the price of fish does not reflect the true scarcity.

THREATS TO THE OCEAN

| The importance of fisheries to the developing economies

The relative importance of trade in fishery products in 2004 for net exporters of such products: fishery exports as a percentage of agricultural exports.

|

Mongabay: Increasingly, there are reports that ocean life is under attack from all sides: over-fishing, climate change, habitat destruction, and nutrient pollution. What measures would it take to preserve healthy oceans for future generations?

Jennifer Jacquet: The solution is very simple. If we stop fishing, fish will recover. But, right now, there is simply too much fishing effort and too little of the ocean is protected. Less than 1 percent of the ocean is closed to fishing! Compare this to the 12 percent of the terrestrial environment that is under protection. We need less fishing effort and more marine reserves. And we need them fast.

Mongabay: Are scientists responsible for bringing to light these issues to the media and public's attention? If so, are scientists doing enough?

Jennifer Jacquet: Scientists have brought a lot of attention to the plight of the oceans over the last decade but this information competes with the beautiful imagery that people often see in nature documentaries and otherwise. The media needs to work more closely with scientists and vice versa so that the problems in the oceans really are in the limelight.

Mongabay: What can the average citizen do to help the situation? Have we reached a point where people should start swearing off seafood altogether?

Jennifer Jacquet: I believe the public must engage primarily in the democratic process and activism rather than simply through personal consumption. If one also chooses to engage as a consumer, convictions about personal consumption and disapproval of certain fish products must be expressed vertically up the supply chain (to chefs, store managers, and seafood suppliers) rather than simply laterally (consumer-to-consumer reproach). Of course, it’s true that if you don’t eat seafood, you don’t have to worry about whether or not it is sustainable.

Mongabay: What gives you hope?

Jennifer Jacquet: That Obama is on the U.S. ballot.

SHIFTING BASELINES BLOG

Mongabay: Can you explain what 'shifting baseline' means and where the term originated?

Jennifer Jacquet: My supervisor, Daniel Pauly, coined the term in 1995. ‘Shifting baselines’ describes how each generation comes to accept a degraded environment as normal.

Mongabay: Why is shifting baselines important to conservation today?

Jennifer Jacquet: If people do not know the baseline, they do not realize what they have lost and they cannot be bothered to care about fixing things.

Mongabay: What kinds of stories do you and your colleagues find for the Shifting Baselines blog?

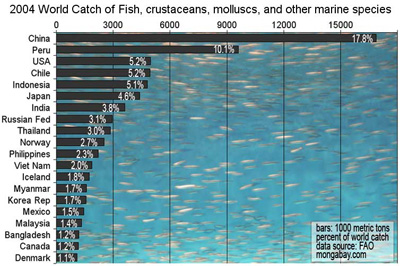

2004 global catch of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and other marine species, based on FAO data. Chart by R. Butler. |

Jennifer Jacquet: We are interested in stories that document changes through time and, moreover, illustrate that those changes are forgotten. My first exposure to shifting baselines was through Mathias Espinosa, a longtime scuba diver in the Galapagos Islands. Mathias explained that during his nearly 25 years in the islands, he heard every diver to come through the islands exclaim that the shark populations were bountiful, despite the evident decline he had witnessed over the decades. Most tourists found it impressive to swim with a couple sharks, let alone hundreds. But divers who had known Galapagos waters since the 1960s and 70s, like Mathias, could recognize the decline in sharks due to their notably earlier baseline.

Mongabay: What are you researching next?

Jennifer Jacquet: I am still reconstructing small-scale fisheries catches in several countries around the world, including Fiji and the Solomon Islands. In these countries, the fish caught and consumed by coastal people do not make it into the national statistics, which is a problem because politicians do not realize how important fish are for food security. I will also continue to work to better understand how we can use the market to help manage global fisheries.