Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

Rhett Butler and Sarah Conway

mongabay.com

August 22, 2007

On August 22, 2007 an edited version of this editorial appeared in the Jakarta Post. What follows is the original version.

This past June, World Bank published a report warning that climate change presents serious risks to Indonesia, including the possibility of losing 2,000 islands as sea levels rise. While this scenario is dire, proposed mechanisms for addressing climate change, notably carbon credits through avoided deforestation, offer a unique opportunity for Indonesia to strengthen its economy while demonstrating worldwide innovative political and environmental leadership.

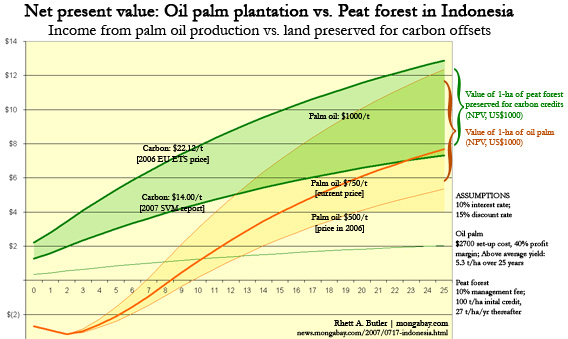

In a July 29th editorial we argued that in some cases, preserving ecosystems for carbon credits could be more valuable than conversion for oil palm plantations (known as sawit kelapa in Indonesia), providing higher tax revenue for the Indonesian treasury while at the same time offering attractive economic returns for investors.

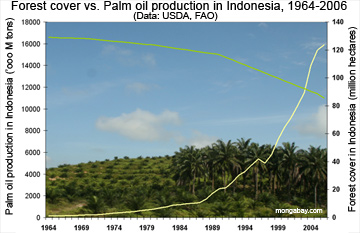

Forest cover versus palm oil production in Indonesia. |

To review, avoided deforestation is the process by which owners, be them governments, communities, or landholders, sell the carbon rights to a given area to private investors. The private investor then sells the carbon credits on international markets to companies looking to offset their emissions. Avoided deforestation is currently only recognized as a voluntary emission reduction (VER) scheme, but it is expected that the concept will be embraced at the December U.N. climate (COP-13) meetings in Bali, especially if proof-of-concept projects are showing signs of success.

Indonesia, thanks to its nearly 20 million hectares of peatland swamps, is well-positioned to capitalize on the growth of carbon credit mechanisms in the future. In fact, conversion, draining, and burning of these peatlands (often for the establishment of sawit kelapa) is presently estimated by Wetlands International, a Dutch NGO, to release some 2 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year. This equates to 8 percent of human global carbon emissions and is why Indonesia is the world’s third largest emitter of carbon after China and the US. While conventional wisdom says that converting these peatlands for sawit kelapa is the best economic use of the land, our analysis shows that carbon credits could prove a better long-term investment for Indonesian businesses and the government. In fact, not only would slowing deforestation and protecting carbon-rich ecosystems allow Indonesia to potentially earn billions of dollars a year from carbon markets, it would also reduce national exposure to price fluctuations of sawit kelapa, as well as the potential risk of European backlash against sawit kelapa as a biofuel.

Here we will take a closer look at these possibilities, using a specific example from the peatlands of Central Kalimantan.

Central Kalimantan

Few places are more suitable for carbon finance projects than Central Kalimantan, which has 3 million hectares of peatlands that store 6.3 gigatons carbon. To illustrate the economic potential of carbon credits versus oil-palm, we compared the net present value (NPV) of a standard 1,000-hectare sawit kelapa plantation to a 1,000-hectare peat swamp preserved for its carbon value.

Sawit kelapa plantation assumptions:

- $2,700 per hectare cost for new plantation development, financed at 10% (published figures)

- Average yield of 4.8 tons of sawit per ha over 25 years (IOPRI/ICRAF)

- Sawit price of $750 per metric ton (current price)

- Net income of 30% (published figures)

- 7% tax rate, discount rate of 16%

Peatland preserved for carbon credits assumptions:

- 10% management cost

- Avoided carbon emissions relative to sawit kelapa: 100 tons per ha for initial forest clearing; 27 tons per year thereafter

- Carbon credits, based on real-world market values averaged for 2006:

- EU ETS Trading Scheme ($22.12)

- Secondary Clean Development Mechanism ($17.76)

- The State of the Voluntary Markets report released last month by Ecosystem Marketplace and New Carbon Finance ($14.00)

- 7% tax rate

Results for business

Our results show that preserving land for its carbon value is worth more than sawit kelapa at present prices for carbon in legally binding markets: $9.99 million for the EU ETS Trading Scheme, $8.02 million for the Secondary Clean Development Mechanism, and $6.32 million for State of the Voluntary Markets report. This compares with $6.58 million in net income over a 25-year period for sawit kelapa plantations. Even if sawit prices were to go to $1,000 per metric ton, net income would still be less than current ETS prices.

Results for government

Carbon credits could also provide the Indonesian treasury with greater tax revenues than sawit kelapa, especially given the recent report that 90% of the country’s plantations had underpaid their taxes (Jakarta Post 14 Aug). At a 7 percent tax rate for carbon, the present value of tax revenue for the Indonesian government ranges from $476,000 to $752,000, whereas the oil palm plantation generates $495,000. In fact, the model suggests that at some carbon prices the Indonesian government could actually charge a slightly higher tax rate for carbon credits than sawit kelapa, and still leave Indonesian businesses better off financially than if they were to rely on sawit kelapa.

These results show that carbon credits offer a great deal of economic potential for central Kalimantan at a low investment cost. Furthermore, carbon offsets are applicable to virtually any part of Indonesia that has intact forests and peatlands. Such a development could make conservation profitable in Indonesia, an important step to protecting the environment and biodiversity.

Given the immense possibility for carbon markets in the future land owners should give serious consideration to carbon values in making land use decisions. While sawit kelapa can and will continue to play an important role in the economy, carbon offsets offer a mechanism to bolster and diversify Indonesia’s financial exposure while at the same time minimizing their negative environmental footprint.

A note about the intended audience for this editorial This editorial was targeted for the business community in Indonesia; specifically companies that already own forest land and are considering clearing it for oil palm. As such, the focus was on profitability. To look at the broader benefits of carbon finance, it would be better to use total revenue rather than net income as well as incorporate some of the other ecosystem services afforded by intact forest. An important component in carbon finance is ensuring that it is structured so that local communities benefit financially, especially through employment. On state- and community-owned lands, carbon finance would be used to fund sustainable development initiatives, like planting crops on degraded lands and reforestation. Local people could continue to subsist from forest areas (possibly non-market timber harvesting, hunting, and collection of forest products like rattan, fruit, and nuts) without degrading the carbon value of the land. Further, in some areas eco-tourism would be a possibility. All the initiatives would be financed using the income from offsets.

|

Related articles

Low deforestation countries to see least benefit from carbon trading

(8/13/2007) Countries that have done the best job protecting their tropical forests stand to gain the least from proposed incentives to combat global warming through carbon offsets, warns a new study published in Tuesday in the journal Public Library of Science Biology (PLoS). The authors say that “high forest cover with low rates of deforestation” (HFLD) nations “could become the most vulnerable targets for deforestation if the Kyoto Protocol and upcoming negotiations on carbon trading fail to include intact standing forest.”

Papua seeks funds for fighting global warming through forest conservation

(8/10/2007) In an article published today in The Wall Street Journal, Tom Wright profiles the nascent “avoided deforestation” carbon offset market in Indonesia’s Papua province. Barnabas Suebu, governor of the province which makes up nearly half the island of New Guinea, has teamed with an Australian millionaire, Dorjee Sun, to develop a carbon offset plan that would see companies in developing countries pay for forest preservation in order to earn carbon credits. Compliance would be monitored via satellite.

Indonesia’s peat swamps worth $39B/year

(7/11/2007) Indonesia’s peat swamps are worth $39 billion in carbon credits per year, according to rough calculations by Bloomberg.

World Bank to raise $250M for avoided deforestation in tropics

(6/11/2007) The World Bank will soon launch an “avoided deforestation” pilot project that will pay tropical countries for preserving their forests, reports The Wall Street Journal. The $250 million fund will reward Indonesia, Brazil, Congo and other tropical forest countries for offsetting global warming emissions. Tropical deforestation accounts for roughly 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, but slowing deforestation slows emissions of heat-trapping emissions. Researchers estimate that “avoided deforestation” schemes may be one of the most cost effective ways to slow climate change. Further, avoided deforestation offers simultaneous benefits including preservation of ecosystem services and biodiversity.

|

Reducing tropical deforestation will help fight global warming

(5/10/2007) Scientists have lent support to a plan by developing countries to fight global warming by reducing deforestation rates. Tropical deforestation releases more than 1.5 billion metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year, though in some years, like the 1997-1998 el Nino year when fires released some 2 billion tons of carbon from peat swamps alone in Indonesia, emissions are more than twice that. Writing in the journal Science, an international team of scientists argue that the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation (RED) initiative, launched in 2005 by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is scientifically and technologically sound, and that political and economic challenges facing the plan can be overcome.