- Mongabay has mapped out the salmon-farming concessions off Chile’s coast and how they overlap with its patchwork of marine protected areas.

- In Chile’s four southernmost regions, five protected areas have salmon-farming concessions within them, with one having more than 300. This threatens the unique ecosystems of Patagonia.

- The 416 concessions that lie inside marine protected areas belong to 32 companies, the top three of which control more than a third of the concessions.

- In 2012, the Comau Fjord witnessed a massive coral die-off that researchers linked to a combination of natural volcanic activity and water oxygen depletion caused by salmon farming.

In 2003, biologist Vreni Häussermann and a group of researchers started surveying underwater life at a site in the Comau Fjord, in Chilean Patagonia. The team found that sea cucumbers, bristle worms, anemones, corals, gorgonians, crustaceans and large schools of mussels abounded in the area. Every year for a decade, Häussermann, a German-Chilean scientist who has studied Patagonia’s marine ecosystems for more than 20 years, wrote down what she observed. Changes from one year to the next were very gradual, but when in 2013 she compared photographs she had taken with those from 2003, she realized there was almost nothing left of what she had seen the first time 10 years ago.

In 2003, dozens of Bolocera occidua anemones lived attached to the steep walls of the fjord’s reefs. Today, there are none left. Also, the density of gorgonians of the species Primnoella chilensis, which were abundant on the reef walls deeper than 20 meters (66 feet), has decreased. “We hardly saw them [rock crustaceans],” says Häussermann, a professor at San Sebastian University in the Chilean city of Puerto Montt. In just 10 years, the density of species decreased by 70%, according to a 2013 paper that summed up the decade of observations. “That is about a quarter of the density we had previously recorded,” Häussermann says.

The researchers concluded that the salmon industry had caused all these changes. The industry cultivates thousands of caged fish destined for export to the United States, Japan and Brazil, among other countries.

Despite the scientifically proven impacts that salmon farming has on natural ecosystems, five marine protected areas in Chile have salmon-farming concessions within them.

What the data show

Chile is the Latin American country with the largest marine area under some category of protection: 41.5% of its maritime territory. It’s also home to the second-biggest salmon-farming industry in the world (behind only Norway), with significant overlap between the two: of the total 1,407 salmon-farming concessions in the country, 416, or 30%, lie within protected marine areas. (The data refer to granted concessions, not all of which are necessarily operating.)

Salmon farming in protected areas

The map shows the total number of salmon farming concessions that have been granted over time, concessions that are within natural protected areas, and those that are pending (not yet granted since they are still under evaluation). You can also search by protected area.

Las Guaitecas National Reserve — which protects the islands of Las Guaitecas Archipelago and the marine area that surrounds it — is the protected area with the most salmon-farming concessions, at 317. Kawésqar National Reserve follows with 67 concessions, and Alberto De Agostini National Park with 19, among others.

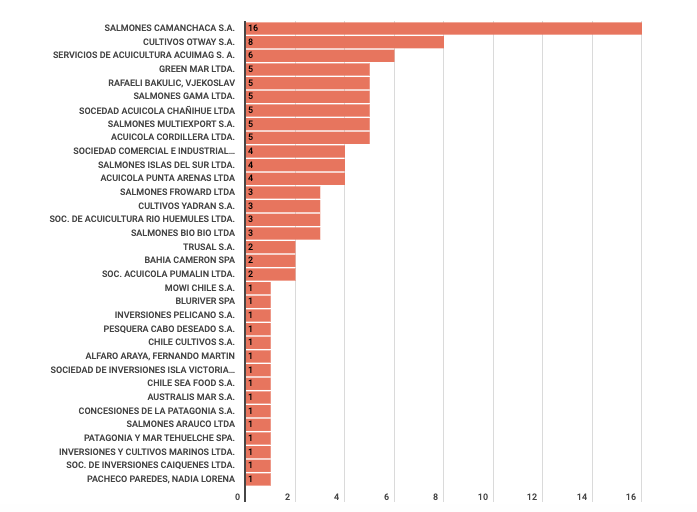

The 416 concessions inside marine protected areas belong to 32 companies, with the top three responsible for more than a third of the concessions.

There are also 271 applications for new concessions still pending and under evaluation by the authorities. Of these, 105, or almost a third, are within protected areas.

Ranking of companies with pending concessions within natural protected areas. Data: Undersecretariat of Fisheries.

Patagonia: A place like no other

Patagonia “is a combination of a very rare fjord ecosystem with large masses of ice like the southern ice field which has a great influence on the ecosystem,” says Alex Muñoz, National Geographic’s Pristine Seas director for Latin America. He says these unique characteristics give rise to numerous species that are only found in the sea around Chilean Patagonia. The area is also a breeding and feeding site for endangered species such as blue whales, and its kelp forests are one of the largest sinks of greenhouse gases, helping reduce the impacts of climate change around the globe.

Despite the environmental importance of Patagonia, few protected areas here remain free from the salmon industry. The area made up of Katalalixar National Reserve, Laguna San Rafael National Park, and Bernardo O’Higgins National Park is the only spot between the two southernmost regions of Chilean Patagonia without any salmon farming, says Liesbeth van der Meer, director of Oceana Chile. It’s possible to see here what the ecosystems further north looked like before the arrival of the salmon farms: “very pristine, very prehistoric,” says van der Meer. “The anemones are very large.” According to Oceana, sea whips, snails, crabs, stars, sea spiders and dolphins all occur in the area. One can also watch sea lions feeding on large colonies of prawns that “on some occasions, spread like a large carpet all over the seabed,” according to an Oceana publication describing the findings from an expedition to Katalalixar.

Underwater photos from Katalalixar National Reserve also give a good idea of what the Patagonian seabed was like before salmon farming. Precise information for each area doesn’t exist, however, as baseline studies were never carried out. Van der Meer says this is the “biggest problem” since it’s not possible to make a comparison like the one Häussermann did in the Comau Fjord to find out exactly what the impacts have been.

The impacts of salmon farming

Studies have shown that one of the main impacts of salmon farming is oxygen depletion in the water, which then leads to the death of marine species in the area.

This happens when salmon feces and excess fish food falls to the ocean floor and accumulates. The nutrients they contain trigger a microalgae bloom, which, according to Häussermann, grows and “lives for just a week or maybe a little longer.” When the algae die and sink to the seafloor, they’re consumed by bacteria that deplete the oxygen in the water, a phenomenon known as hypoxia.

That leaves the seafloor “covered with white bacteria which generally means that there is no oxygen left,” Häussermann says.

“The bottom is transformed into a kind of mud,” van Der Meer adds, and “anemones cannot live there, Chilean basket stars either. Everything that we have documented in Katalalixar cannot live there.”

In October 2007, next to a salmon farm located north of Punta Llonco, in the Comau Fjord, researchers recorded “gorgonians covered by filaments of white bacteria,” and “accumulations of pellets, large amounts of general trash and dumped structures and cables,” according to the 2013 study. During a dive at the same location in March 2008, divers “observed dead gorgonians covered with fine organic sediment,” the study adds.

Those are the direct effects in areas under or near the salmon cages. Other impacts occur further away, which is what Häussermann and her team saw in the Comau Fjord when they recorded the changes in biodiversity over the course of 10 years.

“There are a few species that can take advantage of a great supply of nutrients and thus increase [in numbers], but there are many that are harmed and disappear or decrease” as a result of the hypoxia associated with salmon farms, Häussermann says. In short, when the ecosystem receives an excess of nutrients, the diversity decreases, causing changes that reverberate along the food chain and affect the balance among species.

Among those imbalances is a mass coral die-off that Häussermann and her team recorded in 2012 in the Comau Fjord. The event was quick, she recalls: “One week they were fine and the next everything was dead.”

That year was also marked by high volcanic activity in the region, which dumped large volumes of methane and sulfur in the water. Studies already show that some invertebrates are more vulnerable to hypoxia if they’re also exposed to high levels of methane and sulfur, Häussermann says. After conducting experiments, scientists showed that this was what killed the Comau corals: an excess of methane and sulfur from natural volcanic activity, combined with hypoxia, most likely from salmon farming; oceanographers have ruled out the area as a site where hypoxia occurs naturally.

SalmonChile, the industry association, told Mongabay that “the industry is regulated and is subjected to constant external inspection processes such as Environmental Information Reports (INFA) that evaluate a series of parameters — among them the oxygenation of the seabed — and act as alerts. When recurrent deviations are detected, farm production stops to allow the bottom to return to an adequate condition through natural purification mechanisms.”

But there’s also the issue of the anti-parasitic medication that the salmon farms use against marine lice, a type of crustacean. The problem is that, according to a 2018 study, the anti-lice product given to salmon also inhibits the development of the larvae of other crustaceans. “This is why the rock shrimps [Rhynchocinetes typus] and hermit crabs [Paguristes weddellii] that were common in the Comau Fjord now are hardly seen,” Häussermann says.

Salmon farms have also been criticized for their use of antibiotics, contributing to what is known as bacterial resistance, when the infection-causing bacteria targeted by the drugs mutate and become resistant to the antibiotics.

Another problem is the high number of salmon that escape from the marine cages in which they’re raised. As they enter the natural ecosystem, they put the wild biodiversity at risk, since these carnivorous fish devour a large number of species and don’t have natural predators in these waters. A study published in 2001 analyzed the stomachs of some escaped salmon to find out what they had fed on once outside the cages. It discovered that their diet consisted of crustaceans and other fish, meaning the salmon “could compete with native southern hake and mackerel,” the study said.

To address these issues, SalmonChile says “the industry is developing a series of scientific studies and looking for new technologies that allow any impact to be minimized.” The objective, it says, is to build a more sustainable and ecosystem-friendly activity, given that aquaculture can help ensure food security in an increasingly overpopulated world.

Why is there salmon farming in protected areas?

The answer is simple. Under Chilean fisheries law, the only types of protected areas where the development of fish farms is prohibited are national parks and natural monuments. In all other ostensibly protected areas — from reserves to marine protected coastal areas — salmon farming is allowed. Ultimately, “the reserve definition restricts almost nothing,” says Oceana’s van der Meer.

Ignacio Martínez, a lawyer for the Terram Foundation, says the law isn’t as permissive as as it seems, believe and that the problem is that it has been misinterpreted. While the law allows salmon farming within reserves, the Comptroller’s Office of the Republic has specified that the activity must be compatible with the conservation objectives of each area — that is, it shouldn’t affect the ecosystems and species that the reserve seeks to protect.

The conservation objectives of each protected area are enshrined in its founding charter, Martínez says. If these objectives aren’t clear, the management plan for the given reserve should be reviewed, he adds. This plan not only establishes the conservation objectives but also details how the area is going to be managed, its uses, and the activities that are or are not compatible with the area. “The problem is that many of the reserves do not have a management plan, especially the reserves that have the most salmon farming in their interior, as is the case of Las Guaitecas Forest Reserve and Kawésqar National Reserve,” Martínez says.

Eugenio Zamorano, head of the Undersecretariat of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Subpesca), told Mongabay that although the Comptroller’s Office has indeed stated that aquaculture concessions in protected areas must be compatible with these areas, “in no case the granting of concessions is subject to the existence of their management plans.”

“The controlling entity has taken account of the concessions processed by Subpesca, which validates the legality of the acts of this Undersecretariat,” he added.

Martínez says Chilean law recognizes that “reserves are created for the conservation and use of their natural resources,” and that natural wealth is something that belongs to and is native of a place. “[But] in this case, we know that salmon is an exotic species,” he says — it doesn’t belong in the Chilean ecosystems where it’s raised. In this sense, “the definition of a national reserve is incompatible with salmon farming because it does not correspond to the use of natural wealth,” Martínez says.

The National Forest Corporation, the institution in charge of managing Chile’s protected areas, said in a letter to the attorney for the Comptroller’s Office, Luis Baeza, that “in light of the applicable regulations, it is inappropriate to admit the introduction and exploitation of exotic species within or near a national reserve.” It added that proceeding with this activity goes against Chile’s international obligations on nature conservation.

Another issue with the salmon farms centers on the due diligence that companies are required to conduct prior to operations. Under the environmental law, projects carried out within a protected area must be evaluated by the Environmental Assessment Service (SEA) through an environmental impact assessment (EIA). However, salmon farm projects are systematically evaluated through environmental impact statements (EIS). “The difference is that the statement is a laxer evaluation than the assessment and one of the most important consequences is that it does not have mandatory citizen participation,” Martínez says.

The SEA, responding to the matter, said “it is incorrect to say that Chilean legislation requires that salmon farming or aquaculture projects that are going to be established within a reserve or another protected area, be presented through an EIA instead of an EIS.” According to the SEA, an EIA evaluation “will only happen if the project subject to evaluation is likely to affect” the protected area.

Andrés Pirazzoli, an environmental lawyer and researcher for development organization Confluir, who is also a member of Chile’s delegation to the Paris Agreement, told Mongabay that “the law is clear in saying that all projects that are within protected areas must be evaluated through an EIA” and that “the interpretation that the SEA makes of the law is biased and arbitrary.”

There’s also the fact that, although the law explicitly prohibits aquaculture in national parks, there are 19 salmon-farming concessions in Alberto de Agostini National Park. These concessions are in the process of being relocated, but scientists say they fear this will simply move the problem from one place to another, since they will likely be relocated to Kawésqar National Reserve.

“We have to change the paradigm of protecting ecosystems for the species they contain to also include the services they provide to humanity,” says Muñoz from National Geographic’s Pristine Seas. To do so, he says, “first you have to increase the protected areas at the coastal and marine level in the fjords of Patagonia … and that protection should exclude activities with high environmental impact such as salmon farming.”

Pirazzoli says there needs to be more rigor in evaluating fish-farming projects. “Although the Environmental Assessment Service was created to generate an obligation for the state to caution, its design reflects a preference for fluidity in the [permit] process,” he says. Proof of this, he adds, “is that in the history of the Environmental Assessment Service there has not been a [salmon] project rejected.”

In 2019, a group of senators presented a bill to improve the environmental standards of salmon farming. They proposed a blanket ban on salmon concessions across all types of protected areas. The bill is still pending in the Senate’s environmental commission.

Senator Ximena Órdenes, one of the sponsors of the bill, told Mongabay that aquaculture is important for Chile’s economy; farmed salmon is the second-largest export commodity, after copper. She added that salmon farming is also “a great instrument to combat the adverse effects of climate change, as a substitute for meat.” To achieve this, however, she said “it is necessary to conserve and protect our environmental heritage, and I believe that the minimum requirement to do this is to ensure protected areas function as such and not allow the establishment of industry inside them.”

Citations:

Häussermann, V., Försterra, G., Melzer, R. R., & Meyer, R. (2013). Gradual changes of benthic biodiversity in Comau Fjord, Chilean Patagonia – lateral observations over a decade of taxonomic research. Spixiana, 36(2), 161-171. Retrieved from https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Spixiana_036_0161-0171.pdf

Urbina, M. A., Cumillaf, J. P., Paschke, K., & Gebauer, P. (2019). Effects of pharmaceuticals used to treat salmon lice on non-target species: Evidence from a systematic review. Science of the Total Environment, 649, 1124-1136. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.334

Soto, D., Jara, F., & Moreno, C. (2001). Escaped salmon in the inner seas, southern Chile: Facing ecological and social conflicts. Ecological Applications, 11(6), 1750-1762. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2001)011[1750:esitis]2.0.co;2

Data visualization by Rocío Arias and Daniel Gómez.

Banner image of Katalalixar National Reserve in Chile, courtesy of Oceana.

This article was reported by Mongabay’s Latam team and first published here on our Latam site on March 17, 2021.