This is the first part of a two-part series, the second of which goes more in-depth about the efforts to connect habitat fragments and help secure the future of the Bornean orangutan.

The great apes are among some of the most endangered species on Earth, the targets of poachers and the victims of deforestation. However, from time-to-time there comes news of hope. A study published recently in Oryx describes the dire situation faced by Bornean orangutans, as well as an ambitious project to help save them.

The world’s third largest island, Borneo is shared by three different countries. The largest portion, Kalimantan, belongs to Indonesia. The rest is home to two Malaysian states—Sarawak and Sabah—and the entire tiny country of Brunei. The island is home to the Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), which is listed as Endangered by the IUCN. It is one of the world’s two orangutan species, with the other being the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii), which is considered Critically Endangered. The word “orangutan” itself comes from Malay and Indonesian words meaning “person of the forest.”

Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) in Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

The study was led by Megan Cattau from Columbia University and was carried out in collaboration with The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project (OuTrop) and Center for International Cooperation in Sustainable Management of Tropical Peatlands (CIMTROP). They studied an area of Kalimantan severely impacted by agricultural development and consequential deforestation. This development has severely affected local orangutans, with a 2009 census indicating a population in the region had dropped to between 1,500 and 1,700 from as many as 4,100 individuals in 1995. In other words, the population declined by more than half in just 14 years.

About 20 years ago, the Indonesian government earmarked one million hectares of peat-swamp forest in southern Kalimantan for conversion to rice paddies under the Mega Rice Project (MRP). Substantial investments went into the construction of irrigation canals and leveling forests for conversion. But, as experts had predicted, the project failed and was eventually abandoned after it had considerably damaged the environment.

Forest cover in the area nose-dived from 64.8 percent in 1991, before the project was initiated, to 45.7 percent in 2000. The channels intended for irrigation instead drained out the water from the naturally waterlogged peat-swamp forests, leaving them susceptible to fires that continue to break out on an immense scale, destroying forests and crops, killing wildlife, and producing dangerous haze that is impacting air quality regionally and beyond.

Forest fires in Central Kalimantan in 2006. Photo courtesy of OuTrop.

During the past week (Sept. 29 to Oct. 6), NASA satellites detected 3,501 active fires within Borneo alone. Air circulation patterns bring the smoke to other parts of Southeast Asia, impacting air quality throughout the region. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch Fires. Click to enlarge.

“This study was part of a larger project exploring how land protection could benefit both carbon and orangutan conservation in Indonesian peatlands and the trade-offs between these goals,” lead-author Cattau, who recently returned from Kalimantan, told mongabay.com.

Cattau said they decided to focus their research within the former MRP because they knew orangutans were present but were unaware of their numbers given the fragmented nature of their habitat. The core research site was a 4,500-square kilometer (1,700-square mile) division of the former MRP. Divided into five blocks, A through E, this study focused on Block C largely because although the MRP had resulted in forest clearance, subsequent illegal logging, drainage, fires and degradation, there were fragments of undisturbed forests still surviving within Block C. (At the time of writing, fires were continuing to burn in Block C.)

“This study is the first comprehensive study to research the effects of habitat fragmentation and deforestation on Bornean orangutans in Indonesian Borneo,” Cattau said.

Borneo’s deforestation rate hit a dramatic and historic high in the 1980s and 1990s as extensive logging and oil palm plantations started replacing healthy forests on a commercial scale. Not only did this uncontrolled and largely illegal exploitation destroy contiguous wildlife habitat, but it also paved the way for more commercial interests to set up shop in some of Kalimantan’s most threatened and biodiverse forests.

Of its nearly 54 million-hectare area, more than 14 million hectares of Kalimantan were under timber concessions in the mid-2000s, according to WWF, bringing in $9.2 billion annually in timber exports.

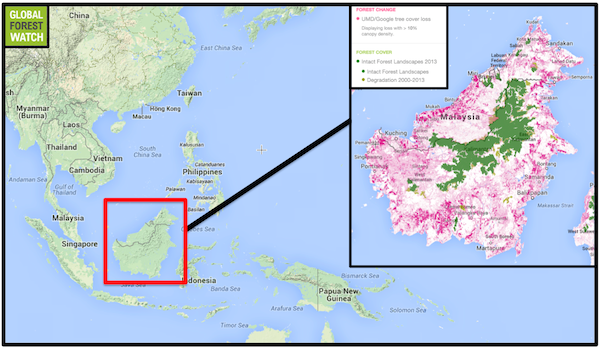

According to data from Global Forest Watch, Kalimantan lost more than 11 percent of its forests from 2001 through 2012, amounting to more than six million hectares of tree cover. However, as harvesting of already-established tree plantations may be confused for forest loss, the amount of actual deforestation is likely lower.

Borneo experienced its highest rate of deforestation in the 1980s and 90s. However, forest loss is still rampant, with approximately six million hectares lost from 2001 through 2012–some of which is likely attributable to the harvesting of plantations. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Tree plantations and timber concessions dominate Kalimantan. Malaysian Borneo is also heavily affected, but data is not yet available to plot their locations and extent. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

This paints a grim picture for species like the endangered Bornean orangutan, which is losing its home to an ever-increasing demand for timber and palm oil. Add to that frequent and devastating fires, hunting and the illegal pet trade, and the orangutan’s odds only seem to be getting worse.

And that is precisely what Cattau and her colleagues at OuTrop and CIMTROP found. Unless crucial and committed steps are taken to conserve their homes and safeguard their future as a species, their prognosis may be dire indeed.

According to the Founder of OuTrop and Director of Conservation, Simon Husson, construction of drainage canals directly led to fires that have destroyed 70 percent of Block C and almost all of Blocks A, B and D. These canals also give access to illegal loggers and an extraction route for cut timber.

“On one side, the largest orangutan population in the world, protected by the Indonesian government; on the other a persecuted population facing extinction unless strong measures are taken,” Husson said, describing the situation facing orangutans in Kalimantan’s Sabangau catchment area.

“A mere 60 years ago, orangutans would have been able to cross the Sabangau River by crossing from tree to tree – which means today there could be cousins on either side.” But now, because of forest clearing, orangutans are no longer able to get from one side of the river to the other, resulting in population isolation.

Pair of orphaned orangutans at the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre in Sabah, Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

According to Cattau, MRP was the biggest player in a host of threats to orangutans.

“The former Mega Rice Project was the main reason for the scale of the degradation,” she said. “We hear that large-scale monoculture oil palm plantations are responsible for forest clearance, but that is not the full story. There is the issue of straight-out forest clearance, but this is coupled with hunting, degraded hydrology, varying levels of forest degradation and fragmentation, forest fires, complicated and often disputed forest tenure…”

And yet, all may not be lost. The next article in this series will discuss how researchers and conservationists are working to save Kalimantan’s orangutans, their achievements thus far, and the hope they’re bringing for the future of Borneo’s “person of the forest.”

|

EDIT: A prior version erroneously stated that the entire orangutan population of Kalimantan was estimated to be between 1,500 and 1,700. This has been amended.

|

Citations:

- Morrogh-Bernard, H., Husson, S., Page, S. E., & Rieley, J. O. (2003). Population status of the Bornean orang-utan ( Pongo pygmaeus) in the Sebangau peat swamp forest, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biological Conservation, 110(1), 141-152.

- Haraguchi, A. (2007). Effect of sulfuric acid discharge on river water chemistry in peat swamp forests in central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Limnology, 8(2), 175-182.

- Megan E. Cattau, Simon Husson and Susan M. Cheyne. Population status of the Bornean orang-utan Pongo pygmaeus in a vanishing forest in Indonesia: the former Mega Rice Project. Oryx, available on CJO2014. doi:10.1017/S003060531300104X.

- Boehm, H. D. V., & Siegert, F. (2001, November). Ecological impact of the one million hectare rice project in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia, using remote sensing and GIS. In Paper presented at the 22nd Asian Conference on Remote Sensing (Vol. 5, p. 9).

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “UMD Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland and Google. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 7 September 2014.

Related articles

(09/16/2014) The orangutan is native exclusively to the islands of Borneo and Sumatra — two regions that have seen the brunt of Indonesia’s recent forest destruction due primarily to logging and plantation development. Although there are anywhere from 45,000 to 69,000 Bornean orangutans remaining in the wild, the Sumatran species numbers only about 7,300 according to a 2004 survey, and is dwindling further every year.

Why are great apes treated like second-class species by CITES?

(09/11/2014) The illegal trade in live chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos and orangutans showed no signs of weakening in the first half of 2014—and may actually be getting worse—since the Great Apes Survival Partnership (GRASP) published the first-ever report to gauge the global black market trade in great apes in 2013.

20 orangutan pictures for World Orangutan Day

(08/19/2014) August 19 is World Orangutan Day, a designation intended to raise awareness about the great red ape, which is threatened by habitat loss, the pet trade, and hunting. Once distributed across much of southeast Asia, today orangutans are only found on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Both species of orangutan — the Sumatran and the Bornean — are considered endangered.

Aceh’s largest peat swamp at risk from palm oil

(08/11/2014) Oil palm plantations and other developments are threatening Rawa Singkil Wildlife Preserve—Aceh’s largest peat swamp, and home to the densest population of Sumatran orangutan in the Leuser Ecosystem. The lack of clear boundaries, and construction of roads bisecting the area has fostered encroachment by local and outside entrepreneurs, including some former local officials, reports Abu Hanifah Lubis, Program Manager of Yayasan Leuser Internasional (YLI).

(07/21/2014) After more than four and a half years of camera trap footage, the results are encouraging: 36 mammal species, of which more than half are legally protected, are prospering in this most surprising of spots: an oil palm plantation in the province of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo.

What is peat swamp, and why should I care?

(07/20/2014) Long considered an unproductive hindrance to growth and development, peat swamp forests in Southeast Asia have been systematically cleared, drained and burned away to make room plantations and construction. Now, as alternating cycles of fires and flood create larger development problems, while greenhouse gas emissions skyrocket, it is time to take a closer look at peat, and understand why clearing it is a very bad idea.

30% of Borneo’s rainforests destroyed since 1973

(07/16/2014) More than 30 percent of Borneo’s rainforests have been destroyed over the past forty years due to fires, industrial logging, and the spread of plantations, finds a new study that provides the most comprehensive analysis of the island’s forest cover to date. The research, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, shows that just over a quarter of Borneo’s lowland forests remain intact.

- Haraguchi, A. (2007). Effect of sulfuric acid discharge on river water chemistry in peat swamp forests in central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Limnology, 8(2), 175-182.