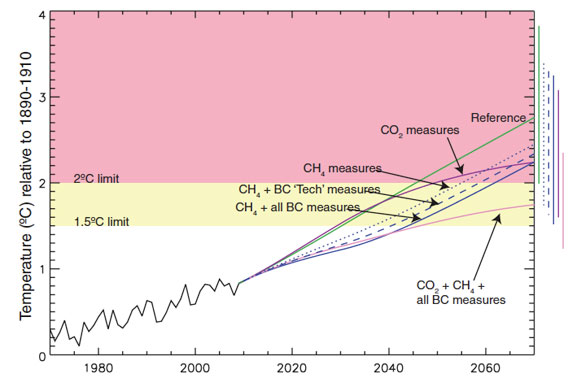

Graph covers observed temperatures through 2009 and projected temperatures thereafter under various

scenarios including cutting methane, black carbon, and carbon, all relative to the 1890–1910 mean. The rightmost bars give 2070 ranges, including uncertainty in radiative forcing and climate sensitivity. Figure 1 of the journal paper “Simultaneously Mitigating Near-Term Climate Change and Improving Human Health and Food Security”, Shindell et al., Science, 2012.

A new study in Science argues that reducing methane and black carbon emissions would bring global health, agriculture, and climate benefits. While such reductions would not replace the need to reduce CO2 emissions, they could have the result of lowering global temperature by 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) by mid-century, as well as having the added benefits of saving lives and boosting agricultural yields. In addition, the authors contend that dealing with black carbon and methane now would be inexpensive and politically feasible.

“Ultimately, we have to deal with CO2, but in the short term, dealing with these pollutants is more doable, and it brings fast benefits,” explains lead author Drew Shindell, a researcher at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “We have identified practical steps we can take with existing technologies. Protecting public health and food supplies may take precedence over avoiding climate change in most countries, but knowing that these measures also mitigate climate change may help motivate policies to put them into practice.”

Agricultural burning of forests and fields (this one in Colombia) produces significant black carbon, which disrupts rainfall, poses health hazards, and warms the Earth. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Black carbon, which is essentially soot, is produced by inefficient burning of wood, dung, coal and other fuels. A major health-issue, soot also impacts rainfall patterns. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas produced by cattle, landfills, and fossil fuel mining and production. When interacting with other gasses, methane forms ground-level ozone, which hurts both agriculture and human health. Both clack carbon and methane are short-lived in the atmosphere: black carbon lasts only a few days to a couple weeks while methane lasts about a decade. In contrast, carbon stays in the atmosphere for around a hundred years.

“These are largely separate and complimentary to reductions in carbon dioxide,” Shindell says in the podcast. “Given their fairly short life times in the atmosphere these pollutants don’t have such a drawn out impact the way CO2 does, and that’s what gives them such powerful leverage in the near term when you don’t have powerful leverage from CO2 reductions. But that means in the long term, what happens to climate is really going to be a function of CO2.”

Looking at over 2,000 ways to deal with black carbon and methane, the scientists eventually selected the 14 most effective. Black carbon could be tackled by replacing inefficient cook stoves in the developing world, filters on diesel vehicles, and banning the burning of farmlands, which occurs largely in the tropics. Methane emissions can be significantly lowered by capturing the emissions from coal mines, fossil fuel-producers, and landfills. In addition, setting regulations on agricultural manure, frequently draining rice paddies, and updating wastewater treatment facilities would further mitigate methane emissions.

The scientists estimated that their recommendations on methane and black carbon would, in addition to slowing global warming, save between 700,000 to 4.7 million people annually due to health benefits and increase annual crop yields by 30 to 135 million metric tons by 2030. The measure would also mitigate regional warming in places like the Arctic and the Himalayas. While it would currently cost around $250 per ton to deal with methane, the authors estimate the benefits would be nearly three times to twenty times the initial investment.

If the world rapidly tackled both black carbon and methane, it would cut rising temperatures by around 0.5 degree Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit). This means, temperatures would still rise, but more slowly. Global temperatures are currently 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.44 degrees Fahrenheit) higher since the Industrial Revolution and recent scientific studies have warned global carbon emissions need to peak this decade and fall swiftly if society is have any realistic change of halting total warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA), not known as alarmist, recently announced that the world had five years to slash emissions or face dangerous climate change.

The scientists say that if the world ambitiously cut CO2 emissions, while implementing the recommended measure against black carbon and methane, warming could be kept to less than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) over the next 60 years.

CITATION: D. Shindell et al. Simultaneously Mitigating Near-Term Climate Change and Improving Human Health and Food Security. Science. 2012.

Related articles

Mixed reactions to the Durban agreement

(12/12/2011) Early Sunday morning over 190 of the world’s countries signed on to a new climate agreement at the 17th UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Durban, South Africa. The summit was supposed to end on Friday, but marathon negotiations pushed government officials to burn the midnight oil for about 36 extra hours. The final agreement was better than many expected out of the two week summit, but still very far from what science says is necessary to ensure the world does not suffer catastrophic climate change.

Current emission pledges will raise temperature 3.5 degrees Celsius

(12/06/2011) New research announced at the 17th UN Climate Summit in Durban, South Africa finds that under current pledges for reducing emissions the global temperature will rise by 3.5 degrees Celsius (6.3 degrees Fahrenheit) from historic levels, reports the AFP. This is nearly double world nations’ pledge to keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). The report flies in the face of recent arguments by the U.S. and others at Durban that current pledges are adequate through 2020.

At least 74 percent of current warming caused by us

(12/05/2011) A new methodology to tease out how much current climate change is linked to human activities has added to the consensus that behind global warming is us. The study, published in Nature Geoscience found that humans have caused at least three-quarters (74 percent) of current warming, while also determining that warming has actually been slowed down by atmospheric aerosols, including some pollutants, which reflect sunlight back into space.

Global carbon emissions rise 49 percent since 1990

(12/04/2011) Total carbon emissions for the first time hit 10 billion metric tons (36.7 billion tons of CO2) in 2010, according to new analysis published by the Global Carbon Project (GCP) in Nature Climate Change. In the past two decades (since the reference year for the Kyoto Protocol: 1990), emissions have risen an astounding 49 percent. Released as officials from 190 countries meet in Durban, South Africa for the 17th UN Summit on Climate Change to discuss the future of international efforts on climate change, the study is just the latest to argue a growing urgency for slashing emissions in the face of rising extreme weather incidents and vanishing polar sea ice, among other impacts.

Top 20 banks that finance big coal

(11/30/2011) A new report from civil and environmental organizations highlights the top 20 banks that spend the most money on coal, the world’s most carbon-intensive fossil fuel. Released as officials from around the world meet for the 17th UN Summit on Climate Change in Durban, South Africa, the report investigated the funding practices of 93 major private banks, finding that the top five funders of big coal are (in order): JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, and Barclay’s.

Another record breaker: 2011 warmest La Niña year ever

(11/30/2011) As officials meet at the 17th UN Climate Summit in Durban, South Africa, the world continues to heat up. The UN World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has announced that they expect 2011 to be the warmest La Niña year since record keeping began in 1850. The opposite of El Nino, a La Niña event causes general cooling in global temperatures.

For poor, climate change “a matter of life and death”

(11/29/2011) In opening the 17th UN Climate Summit in Durban, South Africa yesterday, Jacob Zuma, president of the host country said that delegates must remember what is at stake.

The Pope hopes for responsible climate deal

(11/28/2011) Pope Benedict XVI called for a “responsible” deal at the Vatican today just ahead of the two week Climate Summit in Durban, South Africa.

Greenhouse gases hit new record in atmosphere as officials head to UN climate summit

(11/28/2011) The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere hit a new record in 2010, according to the UN’s World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which found that warming from greenhouse gases rose 29 percent from 1990 to 2010. The announcement was made just a few days prior to officials meet at the 17th Climate Conference in Durban, South Africa, where expectations are low for a strong, binding agreement with a number of wealthy nations stating they expect no new agreement to take affect until 2020.

Arctic sea ice melt ‘unprecedented’ in past 1,450 years

(11/24/2011) Recent arctic sea ice loss is ‘unprecedented’ over the past 1,450 years, concludes a reconstruction of ice records published in the journal Nature.

IEA warns: five years to slash emissions or face dangerous climate change

(11/13/2011) Not known for alarmism and sometimes criticized for being too optimistic, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has warned that without bold action in the next five years the world will lock itself into high-emissions energy sources that will push climate change beyond the 2 degrees Celsius considered relatively ‘safe’ by many scientists and officials.