- Compared to some of South America’s megafauna stand-out species – the jaguar, the anaconda, and the harpy eagle come to mind& – the tapir doesn’t get a lot of love.

- This is a shame. For one thing, they’re the largest terrestrial animal on the South American continent: pound-for-pound they beat both the jaguar and the llama.

- For another they play a very significant role in their ecosystem: they disperse seeds, modify habitats, and are periodic prey to big predators.

Lowland tapir in Yasuni National Park in Ecuador. Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

Patricia Medici will be speaking at the Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 1st, 2011.

Compared to some of South America’s megafauna stand-out species—the jaguar, the anaconda, and the harpy eagle come to mind—the tapir doesn’t get a lot of love. This is a shame. For one thing, they’re the largest terrestrial animal on the South American continent: pound-for-pound they beat both the jaguar and the llama. For another they play a very significant role in their ecosystem: they disperse seeds, modify habitats, and are periodic prey to big predators. For another, modern tapirs are some of the last survivors of a megafauna family that roamed much of the northern hemisphere, including North America, and only declined during the Pleistocene extinction. Finally, for anyone fortunate enough to have witnessed the often-shy tapir in the wild, one knows there is something mystical and ancient about these admittedly strange-looking beasts.

For Patricia Medici, one of the world’s foremost tapir experts, she was instantly endeared to the animal. “I immediately thought [the lowland tapir] was an animal I would love to work with. I found them extremely interesting, mostly due to their role as seed dispersers and ecosystem engineers. In addition, there was so little known about these animals at that point, I thought that a long-term project on tapirs had the potential to make a significant contribution to the conservation of the species and its remaining habitats in Brazil,” Mecici told mongabay.com in an interview.

Patrícia Medici, Coordinator of the Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative in Brazil. Photo by: Liana John. |

Medici is doing pioneering research and conservation work on the lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris) in Brazil. The lowland tapir is the most widespread of the three American tapir species (a fourth species is found in Southeast Asia). After first working with populations in the Atlantic Forest, Medici is now undertaking surveying in the Pantanal.

“The work in the Pantanal is progressing extremely well,” she says, “so far we have managed to capture 21 individuals, 14 of those were radio-collared (we do not radio-collar juveniles and calves). In addition to radio-telemetry, we have been using camera-traps to investigate tapir social organization and reproduction, both very important pieces of information for future tapir population modeling. We have NEVER been able to collect this type of information before. We now have huge amounts of data and information coming in. The main goal is to use this information in a few years to develop an Action Plan for the Conservation of Tapirs in the Pantanal.”

Medici describes the lowland tapir as incredibly ‘plastic’, given that it can survive in the dense jungles of the Amazon, the fragmented habitat of the Atlantic Forest, the wetlands of the Pantanal, and the plains of the cerrado.

It may be strange to think that the biggest animal in South America, and one of the most widespread, has not been thoroughly researched and lacks conservation plans, but being a tapir means long going unappreciated. However, as researchers uncover more about these mega-herbivores they discover that the tapir plays an irreplaceable role in its various ecosystems.

Juvenile male tapir (Picolo) captured in 2008 at Baía das Pedras Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Nhecolândia Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. In the photo, Patrícia Medici and veterinarian Joares May Jr. Photo credit: Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative, IPÊ. |

“[Tapirs] have been recognized as ‘ecological engineers’ as well as ‘gardeners of the forest’. Exclusion experiments carried out with large terrestrial herbivores in Bolivia have demonstrated that tapirs, peccaries, and deer greatly affect ecosystem dynamics. Generally speaking, these animals impact the structure and diversity of plant communities by decreasing the abundance of preferred species, and by changing competitive interactions between plants, therefore maintaining habitat heterogeneity. […] In addition, tapirs selectively browse vegetative parts of different food plants, and seem to have an important role as long-distance seed dispersers. […] Thus, local tapir extinctions or drastic population declines may trigger a breakdown of key ecological processes, jeopardizing the integrity of the ecosystem in the long term,” Medici explains, who this year received the 2011 Research Prize from the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) of the University of Kent in the United Kingdom.

Yet, despite its wide range across 11 countries in South America, the lowland tapir is not wholly secure from extinction. It is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List with a population on the decline. Habitat loss is one of the biggest threats to the lowland tapir, but Medici says even where habitat is secure, other human impacts are imperiling the species.

“Hunting is one of the most important threats. Tapirs are among the preferred game species for subsistence and commercial hunters throughout the Amazon. Estimates of tapir harvest in the State of Loreto in the Peruvian Amazon range from 15,447 to 17,886 individuals per year. Due to their individualistic lifestyle, low reproductive rate, long generation time, and low population density lowland tapirs rarely achieve high local abundance, which makes them highly susceptible to overhunting, and populations show rapid decline when harvested,” Medici says, adding that she believes there is ‘no sustainable levels’ for tapir hunting. Tapir is a popular game animal for indigenous tribes, but is also increasingly sold in rising commercial wildlife-meat markets and restaurants in South America.

“Another serious threat to this species is road-kill. Morro do Diabo State Park in São Paulo, Brazil, is crossed by a highway that, from 1996 to 2006, killed an average of six tapirs per year. Most of the tapirs killed were adult individuals capable of breeding,” Medici adds.

In her research, Medici is finding that conservation efforts for the tapir depend on the ecosystem in which it survives, i.e. tapir conservation in the Atlantic Forest has different priorities than that of the Amazon. The goal is to eventually have a Conservation Action Plan written up for each ecosystem.

Tapir painting by Brazilian tapir Sledge at the John Ball Zoo in the United States. This painting was auctioned during Tapirs Helping Tapirs event held in Brazil in June 2011. Photo credit: Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative, IPÊ. |

Besides conducting on-the-ground work, Medici is working tirelessly to raise the the tapir’s profile in Brazil. She has had to start from the beginning.

“Most Brazilians still do not know what a tapir is. Most Brazilian citizens think that tapirs eat ants (that they are giant anteaters!). In addition, Brazilians associate tapirs with lack of intelligence. Here in Brazil, if you want to call someone stupid you call that person a Tapir! It is the equivalent of ‘jackass’ in English! I want people to hear about tapirs on a regular basis.”

In truth, given its ecological place, losing the tapir in South America would be similar to losing the elephant in Africa or the kangaroo in Australia. Medici, and others involved in tapir conservation, are hoping to make sure this never happens.

In a September 2011 interview Patricia Medici discusses her research on the lowland tapir, how to save the species, and why tapir paintings (yes, that’s right: paintings) have helped raise the species’ profile.

Medici will be presenting at the up-coming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 1st, 2011, an event which will be headed by Jane Goodall.

INTERVIEW WITH PATRICIA MEDICI

Lowland tapir calf at breeding center in Goiás State, Brazil. Photo by: Liana John.

Mongabay: What is your background?

Patricia Medici: I’m a Brazilian conservation biologist whose main professional interests are tapir conservation, tropical forest conservation, metapopulation management, landscape ecology, and community-based conservation. I have a Bachelor’s Degree in Forestry Sciences from the São Paulo University ,a Masters Degree in Wildlife Ecology, Conservation and Management from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, and a Ph.D. Degree in Biodiversity Management from the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), University of Kent, United Kingdom. For the past 19 years, I’ve been working for a Brazilian non-governmental organization called IPÊ—Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (Institute for Ecological Research) of which I was one of the founding members. Since 1996, I’ve been coordinating the Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative in Brazil. Since 2000, I’ve been the Chairperson of the IUCN/SSC Tapir Specialist Group (TSG), a network of over 150 tapir conservationists from 27 different countries worldwide. Lastly, I have been a facilitator of the Brazilian Network of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) for the past six years.

TAPIRS

Adult female lowland tapir at the CERZA Lisieux Zoo in France. Photo by: Daniel Zupanc, Austria.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in tapirs?

Patricia Medici: I have always been very interested in large mammals. When we founded IPÊ in 1992 we were a group of nine people and we created a list of animal species we would like our newly founded conservation organization to work with. The lowland tapir was one of them and I immediately thought that was an animal I would love to work with. I found them extremely interesting, mostly due to their role as seed dispersers and ecosystem engineers. In addition, there was so little known about these animals at that point, I thought that a long-term project on tapirs had the potential to make a significant contribution to the conservation of the species and its remaining habitats in Brazil.

Mongabay: What is unique about these big mammals?

Patricia Medici: Tapirs are often referred to as “living fossils”. The family Tapiridae as a taxonomic entity is first recognizable in the Eocene of North America, nearly 50 million years ago. The genus Tapirus first appeared in the Miocene (25–5 million years ago). Thus, the extant tapirs derive from an ancient lineage and belong to a taxon that has been very successful in the past. Prehistoric tapirs inhabited Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia, including China. No remains have been found on the continents of Africa or Australia. Given the intermittent connections between North America and Asia via the Bering Strait, tapirs soon appeared in Eurasia. With the formation of the Isthmus of Panama between North and South America, during the Pliocene (7–2 million years ago), tapirs entered South America.

Mongabay: What role do tapirs play in the overall ecosystem?

Patrícia Medici and volunteer Kelly Russo collecting tapir fecal samples for genetic, health and diet studies at Baía das Pedras Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Nhecolândia Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. Photo by: Danilo Kluyber. |

Patricia Medici: Tapirs play a critical role in shaping the structure and maintaining the functioning of ecosystems, and thus have been recognized as “ecological engineers” as well as “gardeners of the forest”. Exclusion experiments carried out with large terrestrial herbivores in Bolivia have demonstrated that tapirs, peccaries, and deer greatly affect ecosystem dynamics. Generally speaking, these animals impact the structure and diversity of plant communities by decreasing the abundance of preferred species, and by changing competitive interactions between plants, therefore maintaining habitat heterogeneity. Large animals such as tapirs, even at low population densities, can comprise a significant biomass and consume large amounts of food. Central American Tapirs in Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica, consumed an average of 15.63 kilograms of fruit and fibrous materials per day. In addition, tapirs selectively browse vegetative parts of different food plants, and seem to have an important role as long-distance seed dispersers. Pod-like fruits with small seeds may be chewed with considerable damage to the seeds, but fleshy fruits with large seeds may be consumed whole and the seeds pass through the gut with minimal damage and enhanced ability to germinate. Tapirs ingest whole seeds and either spit or defecate large numbers of viable seeds. These seeds may experience lower rates of predation than seeds not in feces, which suggest that tapirs may increase the effectiveness of seed dispersal if they deposit feces away from parent plants. Thus, local tapir extinctions or drastic population declines may trigger a breakdown of key ecological processes, jeopardizing the integrity of the ecosystem in the long term.

THREATS TO TAPIRS

.568.jpg)

Tapir road kill in highway in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Road-kill is a major threat to lowland tapirs throughout Brazil. Photo by: Patrícia Medici.

Mongabay: What are the biggest threats to lowland tapirs?

Patricia Medici: The lowland tapir has the broadest geographic distribution of the four living species of tapirs and the species occurs in 21 different biomes in eleven countries. Historically, this species was found east of the Andes and north of the Espinal grasslands and shrub lands of Argentina, throughout the Chaco, Pantanal, Cerrado, Llanos, Caatinga, Atlantic Forest, and Amazonian/Orinoco biomes. The historic distribution of the species covered approximately 13,129,874 square kilometers. Nevertheless, populations have been severely reduced and are currently often limited to forested biomes and wetlands. The species is believed to have gone extinct in approximately 14 percent of its range and the current distribution declined to 11,232,018 square kilometers.

The species has been extirpated from the dry inter-Andean valleys of the northern Andes and is becoming increasingly rare along the agricultural frontiers that are sweeping through parts of the western and southern Amazon basin. In Brazil, which constitutes a large portion of its range, the lowland tapir has disappeared from over one million square kilometers (12.4 percent of its countrywide range). Although only about 15–20 percent of the Amazon has been deforested in the past 30 years, 85–90 percent of the Atlantic Forest has disappeared and 40 percent of the Pantanal has been converted to human use. Most of the Cerrado and Caatinga biomes in Brazil have been converted to agriculture and cattle ranching. As a consequence, the Lowland Tapir has been extirpated from the Caatinga; most populations in the Cerrado are small and in protected areas where illegal hunting is minimal. Some exceptions include remote areas of Cerrado (e.g. Chapada das Mangabeiras, Jalapão region in Tocantins State) where tapirs are still common. The Lowland Tapir is now either completely absent or severely fragmented across much of its historic range, with the Northern and Central Amazon as well as the remaining Pantanal (Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay) becoming important strongholds as southern, eastern, and north-western populations are declining rapidly.

The main identified threats responsible for the decline of lowland tapir populations include habitat deforestation and/or alteration; habitat fragmentation (resulting in small populations and low connectivity); hunting; cattle ranching; infectious diseases; road-kill; fire; human density; plantations of monocultures (sugar cane, soy bean); lack of patrolling of protected areas; small size of protected areas; resource extraction; and impact of tourism.

Baby lowland tapir at the CERZA Lisieux Zoo in France. Photo by: Daniel Zupanc, Austria. |

Hunting is one of the most important threats. Tapirs are among the preferred game species for subsistence and commercial hunters throughout the Amazon. Estimates of tapir harvest in the State of Loreto in the Peruvian Amazon range from 15,447 to 17,886 individuals per year. Due to their individualistic lifestyle, low reproductive rate, long generation time, and low population density lowland tapirs rarely achieve high local abundance, which makes them highly susceptible to overhunting, and populations show rapid decline when harvested.

There are a number of infectious diseases (Bluetongue, Equine Encephalitis, Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis, and Leptospirosis) and parasites known in lowland tapir populations in the Atlantic Forest and Pantanal biomes in Brazil. These diseases spread to tapirs from domestic livestock, particularly cattle and horses, and can potentially increase tapir mortality and affect reproductive rates.

Another serious threat to this species is road-kill. Morro do Diabo State Park in São Paulo, Brazil, is crossed by a highway that, from 1996 to 2006, killed an average of six tapirs per year. Most of the tapirs killed were adult individuals capable of breeding. Road-kill is also a serious threat in the Cerrado and Pantanal biomes of Brazil.

Estimates of the total population size for the species throughout its entire range are not available. This species occurs in numerous protected areas across its range. However a large proportion of the total Lowland Tapir population is found outside the boundaries of legally protected areas, where tapirs are hunted, chased by dogs, and face many other threats. Although the species is protected legally in most countries, hunting laws are seldom enforced and have proven ineffective.

Mongabay: Is there still room for hunting tapir by indigenous groups without further imperiling overall populations?

Patricia Medici: My answer would be no. There are no sustainable levels of hunting for tapirs. Due to their life-history characteristics, tapir populations show rapid decline when hunted. The effect of hunting is visible given that tapirs are usually common in areas where there is no hunting and nearly absent where hunting pressure is high.

Mongabay: Is tapir habitat destruction largely the result of big corporations or small-scale farming?

Patricia Medici: It is largely the result of big corporations. In Brazil, particularly, the current levels of habitat destruction are mostly due to large agro-business projects.

Mongabay: If the tapir disappears what other species could be impacted by its loss?

Patricia Medici: Tapirs are widely recognized as “umbrella species,” (species with large area requirements, which if given sufficient protected habitat area, will bring many other species under protection). In other words, meeting the needs of an umbrella species will provide protection for the species with which they co-occur and the wild lands on which they all depend. Other species that could potentially be impacted by the loss of lowland tapirs in Brazil include peccaries, deer, large felines, and rodents among others.

TAPIR CONSERVATION

Adult female tapir (Patrícia) recaptured at Morro do Diabo State Park, the study area of the Atlantic Forest Tapir Program. Photo by: Patrícia Medici.

Mongabay: You started your research in Brazil’s lesser-known Atlantic Forest. How are Lowland tapir populations faring there?

Patricia Medici: Not very well. Tapir populations in the Atlantic Forest are fragmented, small and mostly isolated. Although some of these population may persist in the long-term, their genetic diversity if not enough for their survival.

Mongabay: You’ve started the first tapir research ever in the Pantanal. How is it progressing?

Adult male tapir (Felippe Lion) captured and radio-collared in 2010 at Baía das Pedras Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Nhecolândia Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. In the photo, Patrícia Medici and field assistant José Maria de Aragão. Photo by: Liana John. |

Patrícia Medici: Yes, the Pantanal Tapir Program we have established in the southern Brazilian Pantanal is the first ever to be conducted in this region. When we finished our work in the Atlantic Forest and compared our results with other tapir studies in other countries/ecosystems, we realized that tapirs are very “plastic” and adapt to different habitats/conditions. This means that in order to be able to design conservation strategies for tapirs in a given region, we must have information about their ecology in that particular region. This is the main reason why we decided to expand our work to other Brazilian biomes, starting in the Pantanal.

The work in the Pantanal is progressing extremely well. We have two study areas in two different sub-regions of this biome and so far we have managed to capture 21 individuals, 14 of those were radio-collared (we do not radio-collar juveniles and calves). In addition to radio-telemetry, we have been using camera-traps to investigate tapir social organization and reproduction, both very important pieces of information for future tapir population modeling. We have NEVER been able to collect this type of information before. We now have huge amounts of data and information coming in. The main goal is to use this information in a few years to develop an Action Plan for the Conservation of Tapirs in the Pantanal designing strategies for the conservation of tapirs themselves as well as recommendations for the conservation of their remaining habitats in the Pantanal.

Mongabay: What do tapirs need most to continue to survive in Brazil?

.360.jpg) Adult female tapir (Patrícia) recaptured at Morro do Diabo State Park, the study area of the Atlantic Forest Tapir Program. In the photo, Patrícia Medici, veterinarian Joares May Jr. and field assistant José Maria de Aragão. Photo by: Leandro Abade. |

Patricia Medici: It really depends on where you are in Brazil. If you are in the Atlantic Forest, an extremely fragmented biome (only 7 percent of the Atlantic Forest is left), you must focus on habitat restoration, landscape connectivity, reduction of hunting and mitigation of road-kill. If you are in the Pantanal, you must make sure that the traditional practices of extensive cattle ranching are maintained (traditional practices maintain the forests and native grasses) and you must also worry about mitigating the impacts of infectious diseases (transmitted by domestic livestock). If you are in the Amazon, the main problem is unsustainable hunting by indigenous communities and, today, the high levels of deforestation. Finally, if you are in the Cerrado, it is really a combination of all this. . . The Cerrado is the Brazilian biome that has been suffering the most these days. It has been converted into monocultures such as soybean and sugar cane at very high rates. All the areas outside protected areas will be gone soon.

In all biomes, the creation of protected areas and measures to re-establish landscape connectivity, such as the establishment of wildlife corridors, would be extremely important for tapirs. In addition, the establishment of environmental education programs using tapirs as flagship species would be critical. People must know about tapirs, they must hear about their main threats, they must care.

Bottom line, wherever they are tapirs need the forest and the water. If we could keep those, they would be fine.

Mongabay: How does habitat restoration play into this?

Patricia Medici: Habitat restoration is relevant in some of the Brazilian biomes such as the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado. The establishment of wildlife corridors, buffer zones around protected areas, and stepping-stones between forest fragments would greatly benefit the movement of tapirs between patches of forest as well as the gene flow. It would most certainly increase the viability of tapir populations.

RAISING TAPIR AWARENESS

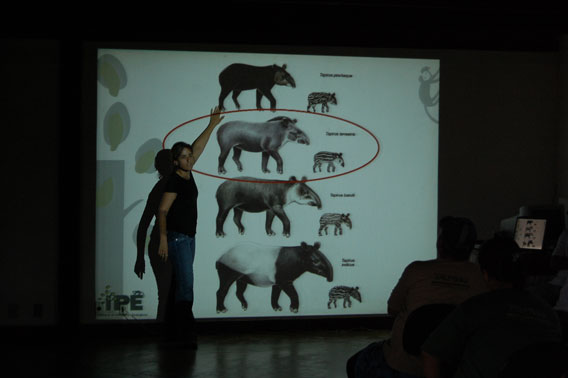

Patrícia Medici, Coordinator of the Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative in Brazil making a presentation to landowners and cowboys at Xaraés Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Abobral Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. Photo by: Joares May Jr.

Mongabay: You’ve raised money for tapirs by selling ‘tapir paintings’. How did this project come about and how do tapirs paint?

Patricia Medici: A few years ago I met a person from the Houston Zoo in the US who told me about similar initiatives carried out by American zoos for orangutans and elephants. Zoo keepers help the animals paint and the paintings are used for “art exhibits” and sold through auctions generating funds for the conservation of these species in the wild. I thought we could do the same with tapirs here in Brazil.

Tapir painting by Malayan tapirs Kelang and Rindang at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington, USA. This painting was auctioned during Tapirs Helping Tapirs event held in Brazil in June 2011. Photo credit: Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative, IPÊ. |

The tapirs do not really paint!!! The keepers help them! They put little drops of ink of different colors in a canvas and spread little pieces of fruit on top of that canvas. Then, they put the canvas in the front of the tapir and the animal brushes its proboscis and chin on the canvas while trying to eat the fruit! Please check the videos on my YouTube channel.

Mongabay: All of the world’s four tapir species are threatened with extinction. Why do you think these animals don’t have a larger profile with conservation groups?

Patricia Medici: I think the problem is 3-fold:

1) Tapirs are not perceived as charismatic species and therefore are excluded from most lists of conservation priorities;

2) Conservation organizations worldwide do not know much about the tapir´s role on the maintenance of forest structure and diversity. In addition, people still do not realize that some of the characteristics of tapirs (long reproductive cycle, long generation time, low population densities etc.) make them particularly susceptible to threats;

3) When it comes to lowland tapirs, most people think that the huge distribution range of the species will guarantee that it will survive. But if we look at the status of lowland tapirs in some of the biomes/ecosystems around South America, we can easily recognize that if we do not do something the species will go locally extinct in several sites very quickly.

Mongabay: What can people do to help save South America’s tapirs?

Patrícia Medici and veterinarian Danilo Kluyber approaching adult tapir in an attempt to dart and immobilize it for the installation of radio-collar and collection of biological samples. Baía das Pedras Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Nhecolândia Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. Photo by: Kelly Russo. |

Patricia Medici: Learn about tapirs; be curious about their threats and conservation status in the wild; care about them; talk about them with your family, friends, work colleagues, teachers; teach your children about tapirs, make them appreciate these wonderful animals since they are little; visit local natural areas and learn to appreciate nature and tapirs; travel to natural places where you can see, learn about, appreciate tapirs; visit the tapirs at your local zoo, observe them, talk to zoo keepers; drive slowly and safely in highways where tapirs can cross, especially early in the morning and late in the afternoon when tapirs are most active; do not buy tapir parts for medicinal purposes; do not buy tapir meat from local markets; plant trees from which tapirs eat the fruits; get involved with local conservation organizations/initiatives, support them; learn about tapir conservation initiatives, support them; promote the creation of protected areas, write letters to local governmental agencies and legislators; if you are a landowner, protect your land, make sure tapirs have enough space and resources to survive, do not use pesticides; if you are a park manager, make sure you take tapirs into account when developing your management plan; if you are a policy-maker, make sure to take tapir conservation into account when writing conservation legislation; make donations to tapir research and conservation initiatives.

Mongabay: What’s next on the horizon for your work?

Patricia Medici: Two main things:

1) The establishment of Tapir Research and Conservation Programs in the Cerrado and Amazon biomes in Brazil. My dream is to see the Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative operating in the four major Brazilian biomes where tapirs occur: Atlantic Forest, Pantanal, Cerrado and Amazon. We will collect tapir data in each biome and design conservation strategies for tapirs in each one of them.

2) The creation of awareness for the tapir conservation cause in Brazil. I have been putting a lot of effort into reaching out to the general public here in Brazil. Most Brazilians still do not know what a tapir is. Most Brazilian citizens think that tapirs eat ants (that they are giant anteaters!). In addition, Brazilians associate tapirs with lack of intelligence. Here in Brazil, if you want to call someone stupid you call that person a Tapir! It is the equivalent of “jackass” in English! I have been working hard to put tapirs in the media as often as possible, and the Tapirs Helping Tapirs event (tapir paintings) was a huge part of that. I want people to hear about tapirs on a regular basis, I want them to wonder why there is this group of researchers dedicating their lives to conserving tapirs, I want them to know that we must care about the survival of tapirs otherwise we will lose our biodiversity.

Adult male tapir (Benjamin Martlet) captured and radio-collared in 2009 at Baía das Pedras Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Nhecolândia Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. Photo by: Patrícia Medici.

Landscape view of the Pantanal during the floods. Photo by: Patrícia Medici.

Radio collared adult female tapir (Mireta) at Xaraés Ranch, study area of the Pantanal Tapir Program in the Abobral Sub-Region of the Brazilian Pantanal. Photo by: Joares May Jr.