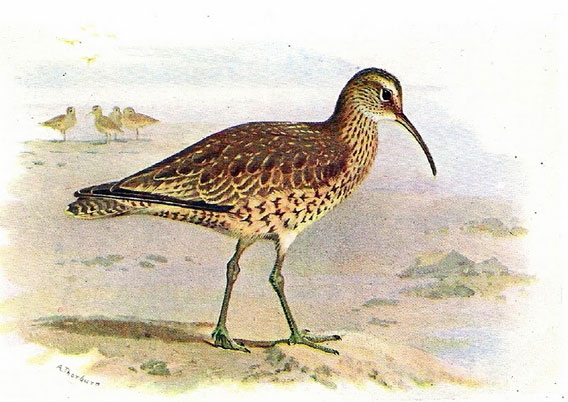

The Eskimo curlew painted by Archibald Thorburn.

The Eskimo curlew is (or perhaps, ‘was’) a small migratory shorebird with a long curved beak, perfect for searching shorelines and prairie grass for worms, grasshoppers and other insects, as well as goodies including berries. Described as cinnamon-colored, the bird nested in the Arctic tundra of Alaska and Canada during the summer and in the winter migrated en masse as far south as the Argentine plains, known as the pampas. Despite once numbering in the hundreds of thousands (and perhaps even in the millions), the Eskimo curlew (Numenius borealis) today may well be extinct. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has decided to conduct a final evaluation of the species to determine whether its status should be moved from Critically Endangered to Extinct, reports Reuters.

The last sighting confirmed by the USFWS was in 1987 in Nebraska, though unconfirmed sightings have continued since. No confirmation of the bird has been made in South America, however, since the 1930s.

The story of the Eskimo curlew’s decline is similar to that of the extinct passenger pigeon: from filling the sky to nearly gone within a few decades. Like the passenger pigeon, the Eskimo curlew was decimated by hunting during the 19th Century. Following the ban of hunting on certain migratory birds in 1916, the bird did not make a comeback. Researchers believe the loss of plains habitat to agriculture as well as the extinction of one of its preferred grasshopper prey made it increasingly difficult for the bird to survive. If the bird still lives, scientists expect it would only be in small, cryptic populations.

This is the first formal review by the USFWS of the Eskimo curlew and will be conducted by researchers in Alaska. Such reviews typically take a year.

Including the Eskimo curlew, there are 8 species of curlew birds in the world. Another of these curlews may be nearing extinction, however. The slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris), which once ranged from Canada to Japan, is currently listed as Critically Endangered with the last confirmed sighting in Hungary, 2001. Researchers estimate there are less than 50 birds alive today.

Related articles

‘No hope now remains’ for the Alaotra grebe

(05/31/2010) World governments have missed their goal of stemming biodiversity loss by this year, instead biodiversity loss has worsened according to scientists and policy-makers, and a little rusty-colored bird, the Alaotra grebe (Tachybaptus rufolavatus) is perhaps a victim of this failure to prioritize biodiversity conservation. Native to a small region in Madagascar, the grebe has been declared extinct by BirdLife International and the IUCN Red List due to several factors including the introduction of invasive carnivorous fish and the use of nylon gill-nets by local fishermen, which now cover much of the bird’s habitat, and are thought to have drowned diving grebes. The bird was also poached for food.

Eastern cougar officially declared extinct

(03/02/2011) The Eastern cougar, a likely subspecies of the mountain lion, was officially declared extinct today by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, ending 38 years on the Endangered Species List (ESA). The cougar, which once roamed the Eastern US, had not been confirmed since 1930s, although sightings have been consistently reported up to the present-day.

Worldwide search for ‘lost frogs’ ends with 4% success, but some surprises

(02/16/2011) Last August, a group of conservation agencies launched the Search for Lost Frogs, which employed 126 researchers to scour 21 countries for 100 amphibian species, some of which have not been seen for decades. After five months, expeditions found 4 amphibians out of the 100 targets, highlighting the likelihood that most of the remaining species are in fact extinct; however the global expedition also uncovered some happy surprises. Amphibians have been devastated over the last few decades; highly sensitive to environmental impacts, species have been hard hit by deforestation, habitat loss, pollution, agricultural chemicals, overexploitation for food, climate change, and a devastating fungal disease, chytridiomycosis. Researchers say that in the past 30 years, its likely 120 amphibians have been lost forever.

Mass extinction fears widen: 22 percent of world’s plants endangered

(09/28/2010) Scientific warnings that the world is in the midst of a mass extinction were bolstered today by the release of a new study that shows just over a fifth of the world’s known plants are threatened with extinction—levels comparable to the Earth’s mammals and greater than birds. Conducted by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; the Natural History Museum, London; and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the study is the first time researchers have outlined the full threat level to the world’s plant species. In order to estimate overall threat levels, researchers created a Sampled Red List Index for Plants, analyzing 7,000 representative species, including both common and rare plants.

Collapsing biodiversity is a ‘wake-up call for humanity’

(05/10/2010) A joint report released today by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Environment Program (UNEP) finds that our natural support systems are on the verge of collapsing unless radical changes are made to preserve the world’s biodiversity. Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Ahmed Djoghlaf, called the bleak report “a wake-up call for humanity.”

Despite promises, world governments failing to save biodiversity

(04/29/2010) In 2002 world leaders committed to reducing the global rate of biodiversity loss within eight years time: 2010. While many have noted that world governments have largely failed on their promises, a new study in Science looks at the situation empirically and agrees that their has been no significant reduction in biodiversity loss and, at the same time, pressures on the world’s species have risen, not fallen.

History repeats itself: the path to extinction is still paved with greed and waste

(04/05/2010) As a child I read about the near-extinction of the American bison. Once the dominant species on America’s Great Plains, I remember books illustrating how train-travelers would set their guns on open windows and shoot down bison by the hundreds as the locomotive sped through what was left of the wild west. The American bison plunged from an estimated 30 million to a few hundred at the opening of the 20th century. When I read about the bison’s demise I remember thinking, with the characteristic superiority of a child, how such a thing could never happen today, that society has, in a word, ‘progressed’. Grown-up now, the world has made me wiser: last month the international organization CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) struck down a ban on the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna. The story of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is a long and mostly irrational one—that is if one looks at the Atlantic bluefin from a scientific, ecologic, moral, or common-sense perspective.