Rangers on elephant back in Sumatra, although most patrols are on foot. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler, 2011.

Twenty-five year old Trevor Frost wants to save parks in Indonesia under attack by illegal logging, mining, and poaching. A lack of infrastructure, support, and funds has left many protected areas around the world to be dubbed ‘paper parks’, protected on paper, but not in reality. Frost, who is currently running in National Geographic’s contest Expedition Granted, hopes to study the problem in Sumatra—among the world’s most imperiled forests and wildlife—and show the world what we are losing even in National Parks.

“My proposed project is one part science and one part advocacy. We will both investigate and expose the paper park problem in Sumatra. The first step of the project will involve scientific research. […] The next step of the project will be documenting, through photos and video, why these parks are struggling to protect the wildlife and environment inside their borders,” Frost told mongabay.com in a recent short interview. “To do so we will tell the story through the eyes of the park rangers and the local community. Together the science and story telling will have a synergistic effect. The research will show what is needed and the storytelling will tell the world what is needed.”

Illegal logging in West Kalimantan’s Gunung Palung National Park. Hardwoods are being trafficked by a timber barons in the town of Ketapang. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2011. |

National Geographic’s Expedition Granted is an online voting contest to award a researcher $10,000 to undertake the expedition of their choice. Frost is currently competing with Dashiell Masland who hopes to study Hawaii’s monk seals in a bid to save the species from extinction [read about Masland’s proposal here]. The winner will be announced on April 7th; the runner-up receives $2,500.

“It is easy to register to vote and only takes a second. People can vote ONCE per day until April 7th. When you vote a second time you only have to enter your email address,” says Frost.

To vote for either candidate: Expedition Granted.

INTERVIEW WITH TREVOR FROST

Mongabay: What is a paper park?

Trevor Frost: A paper park is a protected area or “park” that has little to no on the ground protection, like park rangers or boundary signs, and thus is protected only on paper.

Mongabay: What problems do these protected area often face?

Trevor Frost. Photo courtesy of Frost. |

Trevor Frost: Illegal logging, mining, and hunting are all serious threats to protected areas and parks around the world. No protected area or park is safe. Even in the United States the problem is serious. In Shenandoah National Park, in Virginia, black bears are poached for their gall bladders to extract the bile for traditional medicine in Asia. While there are problems in the United States the problem is far more serious in other parts of the world.

Mongabay: What are these parks most in need of?

Trevor Frost: I’ve personally witnessed the difference one inspired individual can make for one park. As a result I think there needs to be a focus in the conservation community on identifying shakers and movers—in other words

I think we need to pinpoint the most charismatic, respected, noble, and honest individuals living in the local communities around the park in question and empower them to lead protection efforts for the park. Make them the park rangers rather than bringing in people from cities that know nothing of the land or the history. Make the people living around the park the eyes of the forest. WildlifeDirect is one example of a group doing a great job at this.

I also think that satellite imagery, Google Earth, and crowd sourcing are going to begin to play an increasing role in protecting protected areas. The potential is vast. You could have kids in a classroom in Texas monitoring a section of forest in the Amazon with satellite images once every month looking for illegal mining or logging operations and if they find any illegal activities they can report it to the proper authorities via a website.

The other major ingredient to taking better care of our parks is getting conservation groups, both large and small, to begin to focus on taking care of parks once they are created as much as they do on creating them. Unfortunately, at the moment, taking care of parks is not as sexy as creating new ones, so the many go ignored. That said, I don’t think we should stop creating new parks, we just need to stop ignoring existing parks.

Mongabay: What do rangers require specifically?

Trevor Frost: We need more rangers, but we must also provide existing rangers with better equipment and training. Equipment needs include proper uniforms, sturdy boats, binoculars, GPS units, cameras, and vehicles. Training needs are vast. Rangers need to be trained not only how to defend themselves and the wildlife, but they must also learn about the wildlife, their ecology, their behavior, the ecology of the park, the history of the area, and conservation efforts. The other thing to note is that training and equipment go in hand in hand. Cameras and GPS units are linked to training and patrols. If park rangers have and are trained to use GPS units and cameras they can begin to geo-locate all illegal activities they discover. They can also use this technology to geo-locate wildlife sightings and other areas of importance.

On another note, a real goal needs to be having park rangers that actually care about the wildlife and the parks and don’t just see it as a job. An example is Safari Kakule, a ranger who was killed defending mountain gorillas in Virunga National Park. He worked for years without pay and yet in the face of incredible personal danger he set out daily to protect the gorillas. It is also important that rangers are trained in first aid and in dealing with local communities. They need to be ambassadors and not just seen as guardians who protect the park like a fortress, and that is where local communities play a large role.

Mongabay: How can empowering local communities create better park systems?

Orangutans in Sumatra. These great apes are one of thousands of species clinging to life in Sumatra. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Trevor Frost: Local communities are, without a doubt, the key to ensuring protected areas or park systems are successful. We are seeing a major shift in the way conservation is done now—in that many conservation groups, particularly large organizations, are realizing that local communities can no longer be ignored. The people living around these parks, and in some cases inside these parks, are perhaps the strongest weapon against poaching and other illegal activities inside protected areas. They know the land better than anyone. They regularly patrol the area and know the wildlife and where the wildlife is most abundant. They know where the wildlife eat and sleep and all of this information is critical to proper protection.

Mongabay: Why is Indonesia such an important place for paper parks?

Trevor Frost: In Indonesia, the problem is very serious. The Indonesian Ministry of Forestry released a report indicating 37 of their 41 National Parks have illegal logging within their borders. In the worst cases, up to 50% of the parks forests had been impacted by illegal logging. The same report also announced that all of the parks were threatened by illegal hunting and 10 of the parks were threatened by illegal mining operations that have private security forces with automatic weapons to defend their operations. Other serious threats include agriculture and illegal road building by governments and land settlers. It is important that we ensure the parks in Indonesia aren’t paper parks because they are home to some of the world’s most charismatic and endangered wildlife including the Sumatran rhino and the orangutan and because the parks protect ecosystems that provide for local communities.

Mongabay: Will you tell us about your proposal for Expedition Granted?

Trevor Frost: My proposed project is one part science and one part advocacy. We will both investigate and expose the paper park problem in Sumatra. The first step of the project will involve scientific research. To carry this out we will work with scientists from Global Wildlife Conservation as well as scientists in Sumatra to pinpoint those conservation actions that are working and those that aren’t working in 3 national parks—Gunung Leuser National Park, Kerinci National Park, and Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park. This information will be shared with the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry (the government agency responsible for protecting parks in Indonesia) and both local and international conservation groups.

The next step of the project will be documenting, through photos and video, why these parks are struggling to protect the wildlife and environment inside their borders. To do so we will tell the story through the eyes of the park rangers and the local community. Together the science and story telling will have a synergistic effect. The research will show what is needed and the storytelling will tell the world what is needed. This will move the government to act, to some degree, but more importantly it will galvanize the global community and through the spotlight we shine on these parks we will be able to hire additional park rangers, provide them with better equipment, and better training, and engage the local community.

To end, it is important to add two things. First, never doubt the power of the image or video. Think of Sam LaBudde who filmed and released footage of dolphin by catch by tuna fisherman and overnight caused major tuna companies to change their practices. And second, remember that taking care of parks is not as costly as one might assume—the average salary of a park ranger is US $3000—so it doesn’t take a lot to make a big difference in one park as I noted in the beginning of this interview.

Mongabay: Where can people go if they want to vote?

Trevor Frost: People can vote for me here. It is easy to register to vote and only takes a second. People can vote ONCE per day until April 7th. When you vote a second time you only have to enter your email address.

I encourage people to vote everyday and to spread the word using Facebook, Twitter, Blogs, and Email. This would help a lot! Please follow me on twitter @trevorfrost or on Facebook at trevorbfrost.

Related articles

Pulp and paper firms urged to save 1.2M ha of forest slated for clearing in Indonesia

(03/17/2011) Indonesian environmental groups launched a urgent plea urging the country’s two largest pulp and paper companies not to clear 800,000 hectares of forest and peatland in their concessions in Sumatra. Eyes on the Forest, a coalition of Indonesian NGOs, released maps showing that Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) control blocks of land representing 31 percent of the remaining forest in the province of Riau, one of Sumatra’s most forested provinces. Much of the forest lies on deep peat, which releases large of amount of carbon when drained and cleared for timber plantations.

(03/17/2011) Indonesian environmental groups launched a urgent plea urging the country’s two largest pulp and paper companies not to clear 800,000 hectares of forest and peatland in their concessions in Sumatra. Eyes on the Forest, a coalition of Indonesian NGOs, released maps showing that Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) control blocks of land representing 31 percent of the remaining forest in the province of Riau, one of Sumatra’s most forested provinces. Much of the forest lies on deep peat, which releases large of amount of carbon when drained and cleared for timber plantations.

Fighting illegal logging in Indonesia by giving communities a stake in forest management

(03/10/2011) Over the past twenty years Indonesia lost more than 24 million hectares of forest, an area larger than the U.K. Much of the deforestation was driven by logging for overseas markets. According to the World Bank, a substantial proportion of this logging was illegal. Curtailing illegal logging may seem relatively simple, but at the root of the problem of illegal logging is something bigger: Indonesia’s land policy. Can the tide be turned? There are signs it can. Indonesia is beginning to see a shift back toward traditional models of forest management in some areas. Where it is happening, forests are recovering. Telapak understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the ‘new’ forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

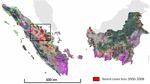

Indonesian Borneo and Sumatra lose 9% of forest cover in 8 years

(02/25/2011) Kalimantan and Sumatra lost 5.4 million hectares, or 9.2 percent, of their forest cover between 2000/2001 and 2007/2008, reveals a new satellite-based assessment of Indonesian forest cover. The research, led by Mark Broich of South Dakota State University, found that more than 20 percent of forest clearing occurred in areas where conversion was either restricted or prohibited, indicating that during the period, the Indonesian government failed to enforce its forestry laws.

(02/25/2011) Kalimantan and Sumatra lost 5.4 million hectares, or 9.2 percent, of their forest cover between 2000/2001 and 2007/2008, reveals a new satellite-based assessment of Indonesian forest cover. The research, led by Mark Broich of South Dakota State University, found that more than 20 percent of forest clearing occurred in areas where conversion was either restricted or prohibited, indicating that during the period, the Indonesian government failed to enforce its forestry laws.