Recently local Alaskan communities were leaked a new draft of a plan to log 80,000 acres of the Tongass forest making its way through the US Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee. According to locals who wrote to mongabay.com, the draft reinforced their belief that the selection of which forests to get the axe has nothing to do with community or environmental concerns.

An arbitrary bill?

“They have taken it on themselves to pick old growth reserves and fisheries habitat to save or give away, not based on scientific reasons but political ones,” Judy Magnuson, community secretary for Port Protection, Alaska, says. “They are doing this without the input of the agency in charge of this, without the biologists and other experts that have spent years designing the new Tongass Forest Plan and the Conservation Strategy designed to create a healthier forest for the future.”

Islands in Southeast Alaska. The Tongass National Forest is the world’s largest temperate rainforest. Photo by: Tyler Poelstra. |

The bill, known as SB [Senate Bill] 881, will hand over some 80,000 acres of prime Tongass forest—55 percent of which is old growth—to Sealaska, an indigenously-owned corporation with a record of clearcutting forests. The Tongass National Forest is the largest temperate rainforest in the world and America’s oldest designated National Forest, which means it is a ‘working forest’ open to a variety of activities including logging and ranching, as well as conservation.

The acreage in question is a part of a promise made by the federal government to Sealaska. In 1971 the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act promised to give indigenous groups in Alaska 44 million acres, 375,000 acres of which were to be located in Southeast Alaska. To date Sealaska has received 290,000 acres, leaving 85,000 acres left under the 1970s agreement. However, critics contend that Sealaska has unsustainably managed the past acreage they were given—clearcutting approximately 80 percent of the land—and that the bill amounts to corporate welfare.

For their part, local communities have become increasingly frustrated by feeling shut out of the process regarding the location of these 80,000 plus acres. While the leaked revised plan showed small-scale tinkering, it failed to address continuing environmental and societal concerns.

“In reading the recent ‘revision’ it is glaringly apparent that the politicians are not listening any more to the scientists from the Forest Service and [Alaska Department of Fish and Game] any more than they have listened to local communities and other public users of the National Forest. A few of the areas have changed. The big picture—that of extensive land grab of important roaded forested areas outside the box, and the effects this would have, has not changed a bit,” Sandy Powers of Ketchikan, Alaska and landowner on Prince of Wales Island, said.

“For [Senator] Murkowski, her staffers, and Sealaska to somehow claim they can throw in ‘acres of old growth habitat here’ for ‘old growth habitat there’ overrides and ignores the opinion of biologists and agencies, and is beyond ridiculous.”

SB 881 has been pushed heavily by Alaskan Senator Lisa Murkowski. Alaska’s other senator, Mark Begich, is co-sponsoring the bill along with Louisiana Senator Mary Landrieu.

Critics say the bill threatens some of the most ecologically unique areas of the Tongass forest, namely karst limestone habitat, as well as two subspecies: the Queen Charlotte goshawk and the Alexander Archipelago wolf.

Small southeast Alaskan communities, who have transitioned from a logging-based economy to one dependent on tourism, believe logging of surrounding areas would significantly impact their economy and way-of-life, which is also dependent on hunting, fishing, and other forest-related activities. Local activists say the best way to stop SB 881 is through New Mexico Senator Bingaman, since he is the Chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

However, in a press release Sealaska has stated that the bill is not only vital to Southeast Alaska’s economy, but to the indigenous tribes that own the company.

“This bill recognizes Native people’s historic relationship with our land for our livelihoods and our culture. And it recognizes the need for our people and communities to have lands that protect Southeast economies, the environment and Native culture,” said Rosita Worl, vice chair of Sealaska’s board of directors and the president of Sealaska Heritage Institute.

Sealaska vice president and general counsel, Jaeleen Araujo, has also tried to reassure local communities of the company’s sustainable practices going forward.

“It’s true that in the past we harvested at very large levels, and that was not sustainable […] But we’re not harvesting at those levels now. We have the ability to manage a sustainable timber program,” she recently told the Los Angeles Times.

A ‘corrupt’ process

Aerial view of the Tongass Forest. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Whatever the outcome, the ex-mayor of Kupreanof, Alaska, David Beebe, says that the process in which the land has been negotiated is “inherently corrupt”.

Beebe contends that SB 881 is being decided through “the now familiar, quid pro quo Wilderness Bill model”, whereby the government considers designating some conservation areas on public land as “somehow commensurate with other large tracts of public land being privatized and deregulated for the purposes of unfettered corporate resource extraction.”

The winner of this process, according to Beebe, is not the public good, but “corporate ends”.

“This gets accomplished through the highly questionable (non-public) process of convening an exclusive group of ‘stakeholders’ to presumably decide what is best for present and future generations of the American public. This model of devolution circumvents the public process, and precludes the deliberative, peer-reviewed science necessary to protect the ecological integrity of the lands being bartered,” Beebe explains.

As far as environmental stakeholders go, Beebe says they have been made largely toothless due to being dependent on funding from corporate foundations.

A better plan?

Powers says that a better plan for the Tongass National Forest has already been drafted by the Forest Service in 2008, and that passage of SB 881 threatens it.

Conservationists say the Queen Charlotte goshawk could become threatened if SB 881 goes ahead. Top: adult Queen Charlotte goshawk. Bottom: Queen Charlotte goshawk nestling. Photo courtesy of the Alaska Fish and Wildlife Service. |

“The Forest Service has listened to the public, engaged in extensive interagency collaboration, followed the relevant land management laws such as [the National Environmental Policy Act], [National Forest Monitoring and Assessment], and others, and come up with what we hope is an economically and environmentally sustainable management plan for the Tongass,” she explains.

According to Powers, the Forest Service’s plan includes transitioning logging to second growth rather than old-growth forests, supporting small business not based on old-growth logging, yet producing enough timber harvest to support small mills in the area. Sealaska has been criticized in the past for ignoring local mills and instead exporting logs directly to Asia for processing in order to make more profit.

Powers says that for Sealaska to “unilaterally appropriate” this forest land will undermine any chance at moving forward with the Forest Service’s plan.

Alan Stein, the former director of the Salmon Bay Protective Association, agrees: “SB 881 spits in the face of long term scientific management of the Tongass National Forest by privatizing 133 square miles for the benefit of a private corporation, throwing long term planning out the window.”

“Sealaska is acting as if they are the only fish in the sea. And Murkowski is acting as if no one else on the Tongass matters except for Sealaska,” Powers adds. “The big question is, ‘Why?'”

Sealaska says that the land in SB 881 is simply fulfilling what was promised in the 1970s.

“We have fought so long for the return of productive, meaningful land for our people,” Byron Mallott, a Sealaska board member, said in a press release. “It is important for all of us who live in the Tongass, as well as those who cherish it from afar, to recognize that the Native people of the Tongass are committed to preserving it as the land of our ancestors and the foundation of our spirituality, values and beliefs. The Tongass is our home. We have nowhere else to go and wish for no other place. This legislation is the final piece of the promise of [the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act].”

For his part Stein wonders why Senator Murkowski is focusing on SB 881 when, according to him, there are more urgent concerns.

“With a million and half gallons spewing into the Gulf daily, it revolts me that the ranking Republican leader of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee [Murkowski] and her staff have taken their eye off the BP Spill,” Stein said, “Senator Murkowski will be asking the committee to waste committee hearings on her revisions to this forestry bill when her committee should be riding rough shod on BP.”

“Why doesn’t Murkowski and her staff let loose of SB 881 and let it die and instead giddy up back to Washington and take care of the most critical environmental disaster in this nation’s history?” he asks.

See below for additional coverage of this issue on mongabay.com. In addition, the organization Alaska Wilderness League has an Action Alert related to the logging.

Related articles

Photos: Tongass logging proposal ‘fatally flawed’ according to Alaskan biologist

(06/15/2010) A state biologist has labeled a logging proposal to hand over 80,000 acres of the Tongass temperate rainforest to Sealaska, a company with a poor environmental record, ‘fatally flawed’. In a letter obtained by mongabay.com, Jack Gustafson, who worked for over 17 years as a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, argues that the bill will be destructive both to the environment and local economy.

Logging in Tongass rainforest would imperil rare species

(05/03/2010) According to a letter from three past employees of the Alaska Division of Wildlife Conservation to Sean Parnell, the Governor of Alaska, a proposal to bill logging the Tongass temperate rainforest would threaten two endangered species. In fact, the letter warns that if the bill passes and the company in question, Sealaska, proceeds with logging it is likely the Alexander Archipelago wolf and the Queen Charlotte goshawk would be pushed under the protection of the US Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Locals plead for Tongass rainforest to be spared from Native-owned logging corporation

(04/29/2010) The Tongass temperate rainforest in Alaska is a record-holder: while the oldest and largest National Forest in the United States (spanning nearly 17 million acres), it is even more notably the world’s largest temperate rainforest. Yet since the 1960s this unique ecosystem has suffered large-scale clearcutting through US government grants to logging corporations. While the clearcutting has slowed to a trickle since its heyday, a new bill put forward by Senator Lisa Murkowski (Rep.) gives 85,000 acres to Native-owned corporation Sealaska, raising hackles among environmentalists and locals who are dependent on the forests for resources and tourism.

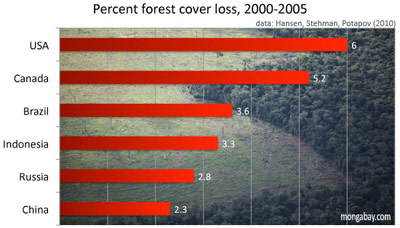

United States has higher percentage of forest loss than Brazil

(04/26/2010) Forests continue to decline worldwide, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Employing satellite imagery researchers found that over a million square kilometers of forest were lost around the world between 2000 and 2005. This represents a 3.1 percent loss of total forest as estimated from 2000. Yet the study reveals some surprises: including the fact that from 2000 to 2005 both the United States and Canada had higher percentages of forest loss than even Brazil.

(03/25/2010) Global forest loss has diminished since the 1990s but still remains “alarmingly high”, according to a preliminary version of a new assessment from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The report, Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010 (FRA 2010), shows that global forest loss slowed to around 13 million hectares per year during the 2000s, down from about 16 million hectares per year in the 1990s. It finds that net deforestation declined from about 8.3 million hectares per year in the 1990s to about 5.2 million hectares per year in the 2000s, a result of large-scale reforestation and afforestation projects, as well as natural forest recovery in some countries and slowing deforestation in the Amazon.