Payments for forest conservation under the proposed REDD mechanism are unlikely to provide a viable economic alternative to oil palm agriculture at current prices.

|

Note from Rhett Butler: History: The following was published in the ITTO Tropical Forest Update (19/1), which came out the week of February 15, 2010. The article was written in 2009 shortly after the publication of “REDD in the red: palm oil could undermine carbon payment schemes” in Conservation Letters. “REDD in the red” was an expansion of work published in 2007 on mongabay.com and in the Jakarta Post. Since publication of “REDD in the red”, several other papers have been published on the subject, including Venter et al (2009) and Persson and Azar (2010). REDD: Despite the passage of a year, the outlook for REDD is not much clearer. REDD was one of the areas of progress during talks in Copenhagen last December and six wealthy countries agreed to provide $3.5 billion for REDD readiness activities between 2010 and 2012, but the talks produced no definitive language on the matter. Observers are now focused on the upcoming Governor’s Climate and Forests Task Force conference in Sumatra for insight on how REDD may proceed down a bi-lateral path. Beyond the economic issues mentioned in this article, the challenges for REDD remain daunting. Concerns over implementation, governance, forestry definitions, finance, project scale and design, and land rights and equity, among others, are unsettled at present. |

In less than a generation oil palm cultivation has emerged as a leading form of land use in tropical forests, especially in Southeast Asia. Rising global demand for edible oils, coupled with the crop’s high yield, has turned palm oil into an economic juggernaut, generating US$ 10 billion in exports for Indonesia and Malaysia, which account for 85 percent of palm oil production, alone. Today more than 40 countries – led by China, India, and Europe – import crude palm oil.

The economic importance of the oil palm industry to Southeast Asia is undeniable. But such financial gains have come at a high price for the native wildlife and traditional rural livelihoods in this region. Conservation scientists have shown that oil palm expansion over the past few decades has led to the destruction of large swaths of tropical rainforests—to the detriment of many rare and endangered species that depend on these forests for survival (Fitzherbert et al. 2008; Koh and Wilcove 2008; Danielsen et al. 2009). Furthermore, social activist groups, such as Oxfam (www.oxfam.org) and Sawit Watch Indonesia (www.sawitwatch.or.id) have documented numerous cases of alleged land-use conflicts between oil palm companies and indigenous communities. Not only are such impacts continuing, but they are likely to intensify in the future as international demand for oil palm products continues to grow.

Oil palm plantation and logged natural forest,

Sabah, Malaysia. Photo: R. Butler/mongabay.com

In an effort to improve plantation management practices, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (rspo; www.rspo.org) was established in 2004 by a group of nongovernmental organizations, oil palm producers and retailers. The RSPO awards certificates to companies that produce palm oil according to a set of principles and criteria. The ultimate goal of the RSPO is to enhance the environmental performance and corporate image of the oil palm industry. However, given the powerful economic forces driving oil palm expansion and the prolonged economic downturn, this is much easier said than done. Indeed, environmental groups continue to produce evidence of forest clearing for new plantings (Greenpeace 2007), while NGOs and regional media report ongoing conflict with local communities from their native lands (www.orangutanprotection. com, sawitwatch.or.id). But even if RSPO proves a success, many operators are not, and have no intention of becoming, members. Further there is little evidence to suggest that RSPO is even finding much of a market for its eco-certified palm oil (CSPO). To date, only 15 000 tons of CSPO—representing ~2.5% of that produced—have been purchased (WWF 2009) [Note: this figure was at the time of press, CSPO sales have since increased to nearly meet production]. At the same time, oil palm plantation continues to spread across the tropics (Butler 2008). Can the palm oil industry be otherwise coaxed towards practices that don’t consume biodiverse and carbon-rich ecosystems?

REDD promise

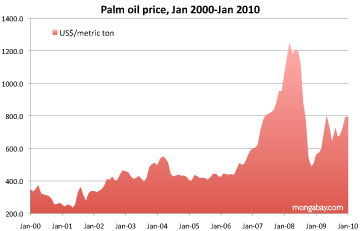

Palm oil price, Jan 2000-Jan 2010. Click image to enlarge. |

A potential solution to might lie in a scheme called Reducing carbon Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD). REDD is being developed as a financial mechanism to compensate land owners, organizations or governments for the value of carbon stored in forests that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere through deforestation (Miles and Kapos 2008). Carbon credits generated from REDD could be used to pay for not only forest protection but also biodiversity conservation and poverty alleviation. But the big limitation presently facing REDD is that credits cannot be used to meet emission reductions obligations, thereby limiting them to voluntary markets like the Chicago Climate Exchange (www.chicagoclimatex.com), where they fetch substantially lower prices than compliance credits traded in the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme. Until REDD credits are recognized under an international climate regime they are unlikely to compete financially with oil palm on most types of land.

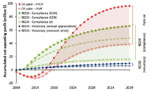

A recent study provides an illustration. Economic models developed to evaluate returns from REDD and oil palm under different price scenarios found that a carbon price of US$18-46 per ton of co2 would be needed to make REDD credits from forest conservation competitive with palm oil. By comparison, credits on the ccx traded in mid-2009 for around US$4 per ton. For peatlands, which lock up large amounts of carbon below ground, the break-even point with palm oil is roughly two-fifths of that—but still outside the range of voluntary market prices. Looking at the calculations in another way, the net present value (NPV) of a REDD project in voluntary markets would range from US$614 to US$994 per hectare over a 30-year project timeframe, as opposed to an oil palm operation that could yield NPVs of US$3835-$9630 per hectare (Butler et al. 2009). Thus it remains more profitable to convert a forest to oil palm than to preserve it for an REDD project.

However, if in future climate policies REDD becomes recognized by the United Nations (UN) as a legitimate activity for reducing carbon emissions, REDD credits would be compensated at higher prices, either via a UN-sanctioned market mechanism or a global fund. REDD could be worth more than $6600 per hectare (Butler et al. 2009) under this scenario, potentially making forest protection an economically competitive land-use option compared to oil palm agriculture or other more profitable land-use activities, especially considering the potential co-benefits of environmental protection.

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. Another way to make REDD more competitive with palm oil is to include below-ground biomass when compensating for avoided greenhouse gas emissions. Clearing, draining, and burning of peatlands is Indonesia’s largest source of emissions in some years. Incorporating these emissions into carbon finance models makes REDD significantly more profitable. In fact, Oscar Venter and colleagues used a spatially=explicit model to find that REDD becomes quite competitive with palm oil when peat carbon is compensated. |

Another recent development that could tip land-use decisions in favor of REDD is that over the last decade or so, large plantation companies rather than small-scale rural farmers have become the dominant driving force of land-use change across the tropics (Rudel 2007; Butler and Laurance 2008; see also tfu 18-4). Many plantation companies now hold large tracts of concessions that are still forested—the sheer extent of which would contribute significantly to biodiversity conservation if they could be preserved. In fact, some plantation companies are already setting aside patches of forests as private nature reserves, driven by pressures from environmental groups, and also as part of the RSPO certification process (Koh and Ghazoul 2009). Furthermore, it’s worth noting that oil palm companies have not always planted oil palm but have often shifted from planting rubber to coconut to cocoa over the last few decades—which suggests that companies may be on the look-out for the next profitable cash crop, which could well be carbon.

Paradigm shift

The adoption of REDD by UN climate policy makers could therefore be a tipping point for the way plantation companies operate and strategize their longterm business plans. It is not unimaginable that through their participation in REDD, some companies could transition from being destroyers of natural forests (with the loss of associated biodiversity) to become their managers and protectors—much as how former wildlife poachers in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America had been successfully turned into effective rangers in nature reserves (Feltner 2009).

This admittedly is a radical proposition. And there undoubtedly are difficult technical, political and ethical challenges to be resolved. Furthermore, the opportunity costs of REDD would be incurred at several societal levels and expressed as both the relatively obvious direct cost (of foregone economic potential) and less obvious indirect costs including impacts on employment, tax revenues, societal and governmental perspectives on financial investments in REDD project regions. There are substantial challenges to overcome if REDD is to be successfully implemented in the future. However, a paradigm shift of this magnitude may be necessary, if not critical, in developing effective strategies for ameliorating the detrimental impacts of oil palm expansion and other forest conversion activities.

References are in the PDF version

Lian Pin Koh and Rhett A. Butler. Can REDD make natural forests competitive with oil palm? [PDF] ITTO Tropical Forest Update (19/1). February 2010.

Related articles

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.

REDD may not be enough to save Sumatra’s endangered lowland rainforests

(11/24/2009) A prominent REDD project in Aceh Indonesia probably won’t be enough to save Northern Sumatra’s endangered lowland rainforests from logging and conversion to oil plantations and agriculture, report researchers writing in Environmental Research Letters. The study highlights the contradiction between the Ulu Masen conservation project; which involves Flora and Fauna International, Bank of America, and Australia-based Carbon Conservation, a carbon trading company and the continuing road expansion, and establishment of oil palm plantations in the region.

Palm oil companies trade plantation concessions for carbon credits from forest conservation

(07/22/2009) Indonesian palm oil producers are eying forest conservation projects as a way to supplement earnings via the nascent carbon market, reports Reuters.

(06/04/2009) A new paper by Oscar Venter, a PhD student at the University of Queensland, and colleagues finds that forest conservation via REDD — a proposed mechanism for compensating developing countries for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation — could be economically competitive with oil palm production, a dominant driver of deforestation in Indonesia. The study, based on overlaying maps of proposed oil palm development with maps showing carbon-density and wildlife distribution in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), estimates that REDD is financially competitive, and potentially able to fund forest conservation, with oil palm at carbon prices of $10-$33 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). In areas with low agricultural suitability and high forest carbon, notably peatlands, Venter and colleagues find that a carbon price of $2 per tCO2e would be sufficient to beat out returns from oil palm.

(06/04/2009) Indonesia’s decision earlier this year to allow conversion of up to 2 million hectares of peatlands for oil palm plantations is “a monumental mistake” for the country’s long-term economic prosperity and sustainability, argues an editorial published in the June issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Can carbon credits from REDD compete with palm oil?

(03/30/2009) Reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) is increasingly seen as a compelling way to conserve tropical forests while simultaneously helping mitigate climate change, preserving biodiversity, and providing sustainable livelihoods for rural people. But to become a reality REDD still faces a number of challenges, not least of which is economic competition from other forms of land use. In Indonesia and Malaysia, the biggest competitor is likely oil palm, which is presently one of the most profitable forms of land use. Oil palm is also spreading to other tropical forest areas including the Brazilian Amazon.

Carbon offset returns beat forest conversion for agriculture in Indonesia

(11/21/2007) Conversion of forests and peatlands for agriculture in Indonesia has generated little economic benefit while releasing substantial amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, reports a new study from the the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and their Indonesian partners.

Avoided deforestation beats timber, palm oil, in tax revenue for Indonesia

(10/29/2007) Indonesia could more than double its tax revenue by protecting forests and selling the resulting carbon emission credits instead of timber and palm oil, a University of Michigan researcher told Bloomberg.

Is the Amazon more valuable for carbon offsets than cattle or soy?

(10/17/2007)

After a steep drop in deforestation rates since 2004, widespread fires in the Brazilian Amazon (September and October 2007) suggest that forest clearing may increase this year. All told, since 2000 Brazil has lost more than 60,000 square miles (150,000 square kilometers) of rainforest — an area larger than the state of Georgia or the country of Bangladesh. Most of this destruction has been driven by clearing for cattle pasture and agriculture, often in association with infrastructure development and improvements. Higher commodity prices, especially for beef and soy, have further spurred forest conversion in the region.

NGOs should use palm oil to drive conservation

(08/29/2007) Environmentalists view the expansion of oil palm plantations in southeast Asia as one of the greatest threats to the region’s forests and biodiversity. Campaigners say oil palm is driving the conversion of tens of thousands of hectares of peatlands and lowland forest in Indonesia and Malaysia, putting wildlife at risk, increasing the vulnerability of the forests to fires, and triggering large emissions of greenhouse gases. Pressure from these groups have in recent months convinced European policymakers to reconsider sourcing energy crop production to the region.

Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

(08/22/2007) This past June, World Bank published a report warning that climate change presents serious risks to Indonesia, including the possibility of losing 2,000 islands as sea levels rise. While this scenario is dire, proposed mechanisms for addressing climate change, notably carbon credits through avoided deforestation, offer a unique opportunity for Indonesia to strengthen its economy while demonstrating worldwide innovative political and environmental leadership. In a July 29th editorial we argued that in some cases, preserving ecosystems for carbon credits could be more valuable than conversion for oil palm plantations, providing higher tax revenue for the Indonesian treasury while at the same time offering attractive economic returns for investors.

Is peat swamp worth more than palm oil plantations?

(07/16/2007) Could peat swamp be worth more intact for their carbon value than palm oil plantations for their oil? Quick analysis suggests yes, though binding limits on emissions will be needed to trigger the largest ever flow of money from the industrialized world to developing countries. At stake: the bulk of the world’s biodiversity.