Reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) is increasingly seen as a compelling way to conserve tropical forests while simultaneously helping mitigate climate change, preserving biodiversity, and providing sustainable livelihoods for rural people. But to become a reality REDD still faces a number of challenges, not least of which is economic competition from other forms of land use. In Indonesia and Malaysia, the biggest competitor is likely oil palm, which is presently one of the most profitable forms of land use. Oil palm is also spreading to other tropical forest areas including the Brazilian Amazon [PDF].

Comparing the profitability of preserving a 10,000 ha forest to reduce emissions from |

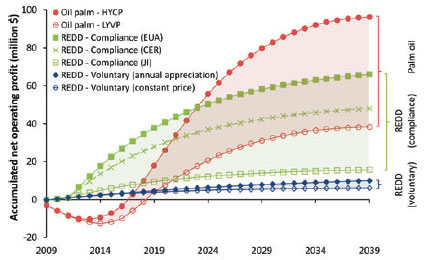

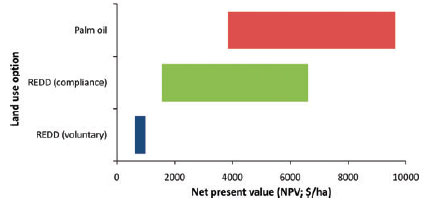

To compare how REDD stacks up with oil palm, ETH Zürich ecologists Lian Pin Koh and Jaboury Ghazoul and I devised economic models to evaluate returns from each land use under different price scenarios. We found that as long as carbon credits from avoided deforestation is limited to voluntary markets where it fetches 10-20 percent of the price in compliance markets like the European Union’s Emission Trading System, REDD will fail to be competitive with palm oil.

-

Our analysis reveals that the development of the concession for oil palm agriculture will generate a net present value ranging from $3,835 to $9,630 per hectare over a 30-year period. Under the second scenario of REDD, we determined that voluntary markets will limit REDD operating profit to $614-$994 per hectare in NPV over the 30-year period–substantially less than profits from oil palm conversion. However, giving REDD credits price parity with carbon credits in compliance markets would boost the profitability of avoided deforestation to $1,571-$6,605 per hectare, and possibly as high as $11,784 per hectare if carbon payments are front-weighted, that is, if credits are allocated and sold during the first 8 years when deforestation actually occurs instead of distributing the credits over the full 30 years.

We believe our results are applicable for both market and non-market mechanisms for compensating tropical countries for avoiding deforestation. |

We of course recognize that economics isn’t the sole determinant of land-use decisions, but it is nevertheless an important one. Furthermore, other ecosystem services — including biodiversity conservation and watershed protection — that may be derived from avoiding deforestation would also augment the environmental and socioeconomic benefits of REDD schemes.

We strongly believe that REDD will be more widely adopted under a climate framework that values forest carbon at levels considerably higher than present. This could happen if REDD becomes recognized by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a legitimate emissions reduction activity during its upcoming Conference of Parties in Copenhagen in December this year.

NOTE: Our models are freely available in Excel (XLS) format.

Butler, R.A., Koh, L.P., and Ghazoul, J. 2009. REDD in the red: palm oil could undermine carbon payment schemes. Conservation Letters DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00047.x

RELATED

Will palm oil drive deforestation in the Amazon?

(03/23/2009)

Already a significant driver of tropical forest conversion across southeast Asia, oil palm expansion could emerge as threat to the Amazon rainforest due to a proposed change in Brazil’s forest law, new infrastructure, and the influence of foreign companies in the region, according to researchers writing in the open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science. William F. Laurance, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama City, Panama, and Rhett A. Butler, founder of environmental science web site Mongabay.com, warn that oil palm expansion in the Brazilian Amazon is likely to occur at the expense of natural forest as a result of a proposed revision to the forest code which requires land owners to retain 80 percent forest on lands in the Amazon. The new law would allow up to 30 percent of this reserve to consist of oil palm.

80% of agricultural expansion since 1980 came at expense of forests

(02/15/2009)

More than half of cropland expansion between 1980 and 2000 occurred at the expense of natural forests, while another 30 percent of occurred in disturbed forests, reported a Stanford University researcher presenting Saturday at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Chicago.

Indonesia may allow conversion of peatlands for palm oil

(02/15/2009)

The Indonesian government will allow developers to convert millions of hectares of land for oil palm plantations, reports The Jakarta Post. The decision threatens to undermine Indonesia’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from land use and fashion itself as a leader on the environment among tropical countries.

New model uses carbon credits, sustainable palm oil to save Indonesia’s rainforests

(02/05/2009)

The World Resources Institute (WRI) has launched an innovative avoided deforestation model that aims to deter conversion of Indonesian rainforest for oil palm plantations. The project, dubbed “POTICO” (Palm Oil, TImber, Carbon Offsets), integrates sustainable palm oil, FSC-certified timber, and carbon offsets in order to “divert new oil palm plantations onto degraded lands and bring the forests that were slated for conversion into certified sustainable forestry”.

Biodiversity of rainforests should not be compared with oil palm plantations says palm oil council chief

(11/11/2008)

Scientists should compare the biodiversity oil palm plantations to other industrial monocultures, not the rainforests they replace, said Dr. Yusof Basiron, CEO of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC), in a post on his blog. Basiron’s comments are noteworthy because until now he has maintained that oil palm plantations are “planted forests” rather than an industrial crop.

Is the Amazon more valuable for carbon offsets than cattle or soy? (10/17/2007)

After a steep drop in deforestation rates since 2004, widespread fires in the Brazilian Amazon (September and October 2007) suggest that forest clearing may increase this year. All told, since 2000 Brazil has lost more than 60,000 square miles (150,000 square kilometers) of rainforest — an area larger than the state of Georgia or the country of Bangladesh. Most of this destruction has been driven by clearing for cattle pasture and agriculture, often in association with infrastructure development and improvements. Higher commodity prices, especially for beef and soy, have further spurred forest conversion in the region. While drivers of Amazon deforestation are stronger than ever, mounting concerns over climate change and the effort to reign in greenhouse gas emissions may provide new economic incentives for landowners to preserve forest lands through a concept known as “avoided deforestation”.