Hundreds of rare and bizarre marine species discovered

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

November 9, 2008

More discoveries from the Census of Marine Life

The evolutionary origin of deep sea octopuses, new species populating an underwater "continent", 12,000 amphipods crowding a square meter in the Gulf of Mexico, massive gatherings of white sharks in the middle of the Pacific: these are just a few highlights from the Census of Marine Life (COML)'s fourth report.

With 2,000 scientists from 82 nations, COML plans to have a full census of all known marine life in two years time. In the meantime, the fourth report released by COML provides a glimpse of the wealth of marine life and the constant opportunity for new discoveries.

"The impressive number of landmark findings over the past two years reveals the richness of what remains to be discovered," French deep-sea explorer Myriam Sibuet commented. "The vastness of the ocean and our new research tools keep marine biology forever young."

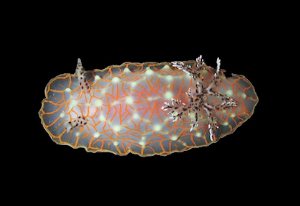

Megaleledone setebos, a shallow-water circum-Antarctic species endemic to the Southern Ocean. It is the closest living relative to the clade of deep-sea octopuses. The specimen shown is a juvenile; adults reach a total length of nearly 1 meter. Photo credit: M. Rauschert. |

One of the most important findings is molecular evidence that many deep sea octopus species evolved from a common ancestor, which still inhabits the water of the Southern Ocean: the Megeleledone setebos, a pinkish-hued deep sea octopus that reaches up to a meter in length.

Researchers hypothesize that octopuses started migrating out of the Southern Ocean on an "expressway" around 30 million years ago. This northbound expressway was created by a cooling Antarctic and increasing ice sheets. Once away, the octopuses evolved to fit their new ecosystems. For example, some lost their defensive ink sacks as they moved deeper into regions which never see light.

An expedition into the Atlantic Ocean's greatest depths caused one explorer to describe the region as "a new continent". Sinking to depths of 2,500 meters below the surface, scientists found hundreds of rare and unknown species in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The explorers covered 1,500 miles in the little explored region, sitting part way between Europe and America.

On the other side of the world, COML made another fascinating discovery, one which has yet to be fully unraveled. Tracking the infamous white shark, researchers found that these super-predators travel long distances every winter to meet in the middle of the Pacific. During this gathering of white sharks, they make dives to depths of 300 meters.

Scientists are uncertain as to why the sharks gather seemingly in the middle-of-nowhere while make periodic dive; hypothesis include specialized feeding or breeding and reproduction.

Migratory behavior has been an essential component of the Census. "Not only do we have a better picture of the distribution of the animals that stay in place, we are approaching a global picture of the movements of animals, whether swirling in eddies the size of Ireland, or commuting 8,000 kilometers across ocean basins," Ron O'Dor, a squid scientist from Canada said. "Understanding how behavior and the environment combine to determine the movement of many animals is within reach."

Four hundred and sixty meters below the surface in the Gulf of Mexico, scientists have discovered a new species of amphipod—a shrimp-like crustacean. This tiny species (6 millimeters long) makes up for its size with vast numbers. The amphipods, named Ampelisca mississippiana, blanket their area, densities reaching a remarkable 12,000 individuals in one square meter. The researchers believe these small amphipods may have great ecological importance.

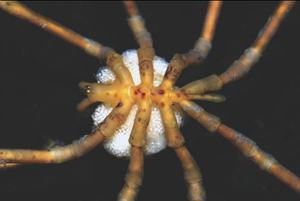

Further south, in the waters of Antarctica, researchers discovered a monstrous amphipod. Fifteen times bigger than Ampelisca mississippiana, this cold-water loving amphipod reaches ten centimeters in length ands is one of the largest in Antarctica.

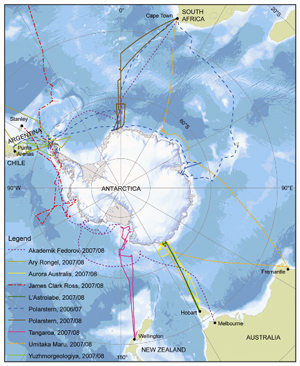

Contrary to what one may expect, the Antarctic and Arctic have proved fruitful places for new species. "Census leadership of the Arctic and Antarctic biodiversity research for the International Polar Year reflects the significance of recent activity," said vice-chair of the COML, Victor Gallardo from Chile. "In 2007 and 2008 alone, Census scientists participated in more than 30 research expeditions." The one that discovered the monster amphipod cataloged a total of one thousand species.

One can only imagine what may be found in two years time. "The release of the first Census in 2010 will be a milestone in science. After 10 years of new global research and information assembled by thousands of experts the world over, it will synthesize what humankind knows about the oceans, what we don't know, and what we may never know – a scientific achievement of historic proportions." Chair of the Census's International Scientific Steering, Ian Poiner said. "Dedication and cooperation are enabling the largest, most complex program ever undertaken in marine biology to meet its schedule and reach its goals. When the program began, such progress seemed improbable to many observers."

These recent discoveries—and many more—will be announced this week at the World Conference on Marine Biodiversity meeting in Valencia, Spain.

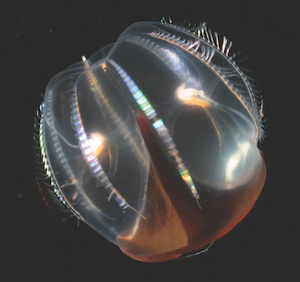

A brightly colored comb jelly swims in the high Arctic waters of the Canada Basin. Photo: Kevin Raskoff, Monterey Peninsula College.

A brightly colored comb jelly swims in the high Arctic waters of the Canada Basin. Photo: Kevin Raskoff, Monterey Peninsula College.