An interview with Dr. Laurie Marker,

founder of the Cheetah Conservation Fund

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 2, 2008

Cheetah population stabilizes in Namibia with support from farmers

Viewing the world's fastest land animal as a threat to their livestock, in the 1980s farmers killed half of Namibia's cheetah population. The trend continued into the early 1990s, when the population was diminished again by nearly half, leaving less than 2,500 cheetah in the southern African country.

Today cheetah populations have stabilized and are on the rise due to the efforts of the Cheetah Conservation Fund, an organization founded by Dr. Laurie Marker in 1990.

The Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) runs a series of programs to protect cheetah habitat, reduce cheetah killing by farmers, and help create sustainable livelihoods and business opportunities for communities sharing landscapes with cheetah. Its initiatives have been wildly successful: the Namibian city of Otjiwarongo is now known as "The Cheetah Capital of the World". CCF is today seen as a model for cheetah conservation efforts throughout Africa.

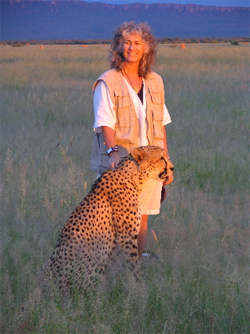

Laurie Marker and Chewbaaka, an orphaned cheetah. Courtesy of CCF |

Marker says that a key part of the shift has been changing people's perception of the cheetah, which among farmers, has long been viewed as a threat to livestock. CCF's educational program explains the role of predators in the ecosystem and teaches how to farm using predator friendly techniques. CCF also breeds and donates livestock guarding dogs to help reduce livestock losses to predators by up to 80 percent in some areas.

"Today, many more people see the cheetah as an asset versus just vermin," Marker told mongabay.com in an interview ahead of her upcoming visit to the U.S. "We have many livestock farmer friends who have learned how to co-exist with cheetahs."

"Because CCF tries to help farmers who have a predator problem, we are trusted by most locals. We don't wag our finger at people who have killed cheetahs; on the contrary, we try to help them and make them our friends so they will think twice before killing another cheetah. It's worked extremely well. Whenever we drive around in our cheetah bus or other CCF vehicles, people wave to us like we're celebrities."

Noting that Namibia already sees millions of dollars in revenue from tourists coming to see cheetah and other wildlife, Marker says CCF is developing ways for farmers to benefit directly from cheetah conservation.

|

"Some of our business initiatives include certifying our Conservancy farmers to sell our beef as cheetah friendly. For instance, if we can get our Cheetah Country Beef project off the ground, it will pay a price premium to farmers who use predator-friendly farming practices–the cost will be absorbed by the consumer of beef (actually some of the best beef in the world, as the cattle are range fed)."

"[CCF] It also runs a factory that takes harvested invasive bush, which is destroying the cheetah's habitat, and turns it into a variety of products, including a clean-burning fuel log called the Bushblok. The plant provides jobs and income to over 30 locals [and helps] restore the cheetah's habitat."

Marker will be discussing these initiatives and other CCF programs this Saturday at the Wildlife Conservation Network's Wildlife Conservation Expo in San Francisco, California. The event, which is open to the public and costs $25-50 per person, also features 16 other conservationists working to protect wildlife around the world.

AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. LAURIE MARKER, FOUNDER AND DIRECTOR OF THE CHEETAH CONSERVATION FUND

Mongabay: What led you to work on cheetahs?

Laurie Marker: I've always been into animals—I grew up on the back of a horse and had dogs, rabbits and loved all farm animals – in particular goats. I got my 1st cat when I was in high school, because my grandmother was afraid of them, I fell in love with my cat. Through my developmental years I was an avid Future Farmer and learned about agriculture, livestock husbandry and wildlife management.

I moved to Oregon, from the Napa Valley where I was educated in viticulture, and took my small dairy goat herd with me to Oregon. I moved to Oregon, near Oregon's Wildlife Safari, to start a vineyard and winery (I was one of the pioneers of the Oregon wine industry). I needed a job to support my business, and with my background working with horse vets growing up, I went to the Safari and asked for a job.

My first main job in 1974 was running the wildlife veterinarian clinic at Wildlife Safari in Oregon. This is where I first met cheetahs. These wild cheetahs came under my care along with a couple hundred other species of wildlife. I learned about the problems facing our world's vanishing wildlife and my research focus took me to finding out more about cheetahs.

Laurie Marker and Chewbaaka, an orphaned cheetah. Courtesy of CCF |

I was always intrigued by the mysterious cheetahs, who were kept off exhibit so they could have the privacy to breed. The first time I saw one, I was immediately hooked, and I immersed myself in learning about them. I contacted everyone who knew anything about cheetahs, only to find out that nobody really knew very much. So I soon became the cheetah "expert." In 1976, I was asked to participate in a first of its kind research to take a captive born cheetah back to Africa to see what step were need to teach it how to hunt. And in 1977, I was given a female cheetah cub, who I named Khayam, to hand-raise for this research project.

We were inseparable, and when she was a year old she and I went to a country in Africa then known as South West Africa, and today known as Namibia, to see if hunting is instinctual or learned in a cheetah. (This was filmed for a television show called “American Sportsman" for ABC.) It was while I was in Africa for the shooting of that documentary that I first learned that farmers were killing 800-900 cheetahs a year.

Back in Oregon, I developed the most successful captive breeding program for cheetahs in North America. And in 1982 began a collaborative research project with scientist from the National Cancer Institute and the Smithsonian's National Zoo, where we discovered the genetic uniformity of cheetahs and the species vulnerability to disease and reproductive problems plaguing the species.

I continued to travel to Africa and kept ending up in Namibia. I knew that a conservation program for cheetahs in the wild was need. I kept thinking that some big conservation organization would take on saving the cheetah.

In 1988, I moved to Washington DC to join the research team at the Smithsonian's National Zoo to continue with cheetah research. But I couldn't get the thought of how many cheetahs were being killed indiscriminately in Africa out of my head. Finally, I decided that in order for me to really make a difference in the survival of the cheetah, I had to be in Africa. So in 1990, after Namibia's war of independence was over, I moved to the country and established the Cheetah Conservation Fund.

Mongabay: Where is the Cheetah Conservation Fund active?

Laurie Marker: The Cheetah Conservation Fund is an international conservation NGO with its headquarters in Namibia. CCF has another permanent field station in Kenya and works on projects in Algeria, Botswana, Ethiopia, Iran, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. In addition, CCF has helped to develop permanent programs for cheetahs in Botswana (Cheetah Conservation Botswana) and in Zimbabwe. But we're in the process of expanding our methods for teaching farmers how to live peacefully with predators to all the cheetah range countries. Just this summer CCF conducted the first international courses on Integrated Wildlife and Livestock Management and Conservation Biology Field Training course for conservation biologists from more than a dozen cheetah range countries. We plan to hold a total of six of these courses over the next three years. Our goal is to train a network of regional professionals collaborating on regional cheetah strategies, so that the impact will expand from local pockets of protection dotting the cheetah's range countries to much broader, far-reaching and inter-connected swaths.

Laurie Marker interviews a farmer’s wife in Namibia. Courtesy of CCF |

CCF's programs include research and publishing findings on the health and genetics of the cheetah – we have developed a very large database on the cheetah (one of the largest for any endangered species in the world) that contains information on the cheetah's health, morphology, genetics, movements, range and territories. CCF collaborates with scientists throughout the world in analysis of the data. In addition, we have been working on a census of the Namibian cheetah population through various research techniques like using camera traps and identifying individual cats through DNA found in scat.

CCF's conservation programs include helping farmers reduce livestock loss. One of our programs includes the breeding and donating of Livestock Guarding Dogs to farmers, which I talk about in more detail later. Farmer training programs teach about the role of a predator in the ecosystem and how to farm using predator friendly techniques, like having a concentrated breeding season for livestock or allowing wildlife on your property so predators aren't tempted to catch livestock.

CCF's education programs raise awareness about the cheetah internationally. Locally, we teach how to live with a cheetah and other environmental education and natural recourse management aspects that are unique to Namibia.

Mongabay: What are the biggest threats to cheetah where CCF works?

Laurie Marker: By far, the biggest threat to the cheetah is lack of habitat resulting in human wildlife conflict. Cheetahs can't be hemmed into reserves or parks–their territories are too large, and bigger predators such as lions and hyenas usually will out compete with them by stealing their kills or killing their cubs, resulting in them moving out of these protected areas. So over 90% of all cheetahs are now found outside protected areas on livestock farmlands. Because they are day hunters, cheetahs are more visible than leopards and other predators, so they get blamed for a lot of livestock kills, regardless of whether they were the culprit. And it is legal to kill a predator that is believed to have killed livestock. So a large part of what CCF does is educating farmers about ways they can minimize the threats to their livestock. With proper livestock management, farmers can eliminate their loss to predators. But it's a long process to change such strongly held beliefs.

Namibian farmers receiving their guard dog puppies. Courtesy of CCF |

For the cheetah to survive into the future, we need to create large, interconnected landscapes that will support cheetahs, their prey, and human livelihoods. Right now, the much of the land where cheetahs are found in southern Africa is divided by fencing that prohibits migration. I am a strong proponent for what are known in southern Africa as Conservancies, where there are no fences and farmers cooperatively manage their wildlife. The organization in Namibia I work with is called the Conservancy Association of Namibia (CANAM). I have been the Chairman of this organization for the past five years. We understand that if African wildlife is to survive, we need to change the face of Africa and work towards large areas that are not fenced working with people on who's land the wildlife and cheetah are living.

Mongabay: What is your outlook for the species?

Laurie Marker: Getting cheetah populations stabilized will be tough. Aside from the human conflict issue, cheetahs face a host of other obstacles. One is that a die-off approximately 10,000 years ago left only a few cheetahs. So from that extremely shallow gene pool evolved today's cheetahs, which have almost no genetic variation. This has caused many problems, including physical abnormalities, low fertility rates and a vulnerability to disease. In addition, they are losing their habitat to development and desertification. But I firmly believe that we can save them, or I would never have moved to Africa. We've seen the numbers of kills by humans level off in most of Namibia over the last 18 years, and as landowners become more educated about wildlife conservation, many are changing their attitudes about predators and actually working toward their survival. As a model for the rest of cheetah range countries, our work now is to help get the rest of their range countries to follow suit.

Mongabay: Is peaceful co-existence between cheetah and farmers/ranchers possible?

Laurie Marker: There will always be livestock farmers (ranchers) who will never change their minds about predators, but we have many livestock farmer friends who have learned how to co-exist with cheetahs. Many have even come to see them as an asset. They bring tourism, which helps the economy. In Namibia, and around Africa, conservancies are becoming popular. Conservancies are made up of neighboring farmers and ranchers who have similar ideas about how the properties can band together to protect wildlife. Conservancies play an important role in restoring more natural migration routes for wildlife, and keeping a balance between predators and their natural prey. So, while I still feel a strong sense of urgency that things have to change quickly, I'm optimistic that they will change – I am taking an active role in making this change happen.

To cooperatively manage their natural resources; game, livestock and predators, CCF works in conjunction with its neighbors in the Waterberg Conservancy. This area is about 400,000 acres of wildlife and cheetah friendly lands. We have found that Namibia's younger generation of farmers is more tolerant of predators and cheetahs.

Today, many more people see the cheetah as an asset versus just vermin.

From our core area around the Waterberg Conservancy, we are working together with our local subsistence communities to develop conservancies and have developed an area that is now known as the Greater Waterberg Complex – this area is nearly 4 million areas. We are helping to develop this into an area that can become the 1st cheetah and wild dog conservancy in Africa.

In addition, we run a model livestock farm which is used as a teaching center for hundreds of Namibian farmers each year. We practice what we preach and have cattle, goats, sheep, livestock guarding dogs, along with an integrated wildlife system of hundreds of head of free-ranging antelope, wild cheetahs, leopards, and all the other species in our Namibian ecosystem.

Mongabay: CCF runs an interesting program involving livestock guarding dogs. Can you explain how this works?

Laurie Marker: People have used dogs to guard their herds of goats and sheep for centuries. Although having dogs with flocks in Africa, most of the dogs they own are not guarding dogs and as such are too small to protect against predators like cheetahs or jackals or predators. After conducting several years of research into causes of livestock mortality in Namibia, in 1994, I began CCF's Livestock Guarding Dog program, using the Kangal (Anatolian Shepherd), a breed of dog that has been used in Turkey for several thousand years to protect sheep from wolves. These dogs were chosen over other livestock guarding dog breeds because they are able to work unsupervised in vast open spaces, are short-coated—making them well adapted to working in a hot, arid climate—and are large, imposing dogs that bark loudly to chase away potential predators. The program is designed to provide a method of non-lethal predator control that protects the farmer's livelihood without harming the predators.

Kangal livestock guarding dog in action. Courtesy of CCF |

Today, CCF has bred nearly 300 Kangal livestock guarding dog puppies and donates them to livestock farmers.

CCF breeds, places and monitors the livestock guarding dogs. Puppies are closely monitored for the first six months after placement with at least one site visit that includes their follow-up vaccinations; initial vaccinations and neutering are done at CCF before placement. In addition, monitoring includes investigating livestock losses to predators on farms with and without guarding dogs.

CCF provides for funds vaccinations, neutering, and some medical care, in particular, for dogs on communal subsistence farmlands. Ideally the dog's owner would provide all care once the dog is placed. However CCF has learned that providing this extra level of support ensures the success of the dogs in locations where perhaps they are the most useful. Dogs are usually placed where conflict with cheetahs is greatest.

The CCF's Livestock Guarding Dog program has generated much interest among farmers, communities, tourists and the media since its inception in 1994. At the end of 2007 there were over 130 livestock guarding dogs working in Namibian communal and commercial farms. On farms where dogs are working, livestock losses have been eliminated or reduced (farmers have reported up to an 80% decrease in livestock losses post-placement). The burden of convincing a farmer not to kill or harass a cheetah is greatly reduced when the farmer does not perceive the cheetah as a threat to his/her livelihood.

Mongabay: How is your work received by local communities? What are ways local people can benefit from cheetah conservation?

Laurie Marker: Because CCF tries to help farmers who have a predator problem, we are trusted by most locals. We don't wag our finger at people who have killed cheetahs; on the contrary, we try to help them and make them our friends so they will think twice before killing another cheetah. It's worked extremely well. Whenever we drive around in our cheetah bus or other CCF vehicles, people wave to us like we're celebrities.

The Cheetah Conservation Fund spends more than $1.5 million annually in Namibia on salaries, goods and services. CCF employs 45 Namibians at its International Research and Education Centre headquarters near Otjiwarongo. It also runs a factory that takes harvested invasive bush, which is destroying the cheetah's habitat, and turns it into a variety of products, including a clean-burning fuel log called the Bushblok. The plant provides jobs and income to over 30 locals.

Additionally, CCF attracts thousands of eco-tourists who spend money for goods and services while in country. Through CCF's efforts over the past 18 years, Otjiwarongo is now known as the Cheetah Capitol of the World. Namibia is very proud of its wildlife.

Mongabay: How can in the U.S. people help the cheetah?

Laurie Marker: As a nonprofit organization, everything we do depends on donations. I would give anything not to have to ask for donations to try to save the cheetah – but I am only one person without a very large pocket book. I put my entire life into saving the cheetah. The cheetah does not have anything to buy or sell; it's not a business, it's an endangered species. I often wonder what people expect from or for our endangered species. How can they help themselves? They need help from humans.

Kangal live |

Beyond donations, as I mentioned before, we need to change the face of Africa if we want to ensure the cheetah's survival. CCF will partner with any and all who want to help this change occur as rapidly as possible. We need partners who think big—U.S. corporations and businesses working in cheetah range countries, for example. In addition, we have an opportunity to help CCF through eco-tourism and are asking for partners in helping to develop a tented camp at CCF as well as having an opportunity to purchase more land, a critical piece of land, right in the middle of CCF's reserve.

Some of our business initiatives include certifying our Conservancy farmers to sell our beef as cheetah friendly. For instance, if we can get our Cheetah Country Beef project off the ground, it will pay a price premium to farmers who use predator-friendly farming practices–the cost will be absorbed by the consumer of beef (actually some of the best beef in the world, as the cattle are range fed). Then, we can increase habitat through the habitat restoration project we are doing with our Bushblok. It's marketed as a tool to help restore the cheetah's habitat, again a way that a consumer can help the cheetah survive. We continue to look at these types of business ventures where consumers can help. If anyone has any ideas, send them along—we will consider anything!

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring conservationists?

Laurie Marker: We need a lot more biologists and conservationists, so this is a topic near and dear to my heart. A good education is key, although Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and I learned most of what we know on the job. What all great conservationists and biologists have in common is a passion for what we do, an overriding need to help our respective species. It's a 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week, 365-day-a-year job. So if that doesn't scare you off, then great! CCF takes volunteers and interns, and we try hard to foster future conservationists, both locally and globally. But my best tip would be to never give up. It's too important.

Related

Group takes “venture capital” approach to conservation

|

(09/16/2008) An innovative group is using a venture capital model to save some of the world’s most endangered species, while at the same time working to ensure that local communities benefit from conservation efforts. The Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), an organization based in Los Altos, California, works to protect threatened species by focusing on what it terms “conservation entrepreneurs” — people who are passionate about saving wildlife and have creative ideas for dong so. After a rigorous review process to identify and select projects that will have the greatest impact on conservation in developing countries, WCN provides the conservationist with fund-raising and back-office support, technology, and access to its network of people and resources.