Emerging regional and national networks seek to build connections between local communities and provide support to their fights against dams, mines, and other environmental threats.

An anti-mining protest in the mountain town of Artvin, Turkey. Photo: Green Artvin Association.

An anti-mining protest in the mountain town of Artvin, Turkey. Photo: Green Artvin Association.

Neşe Karahan pointed out the car window as it wound its way through a snow-covered pine forest on a chilly morning this April. “Over there, that’s the mining reserve; on the other side of the hill, that’s the ski area,” she said. “It’s such a ridiculous thing: This same place is where our water comes from, where we go picnicking in nature — and a mining area.”

Karahan brings out a map to highlight the absurdity: Other than the ski resort, nearly all of this mountainous region in far eastern Turkey lies within the overlapping boundaries of both an area designated for mining and an area designated for tourism.

“Walking in these mountains is so wonderful, it’s like walking on a soft carpet. We have 40 different kinds of orchids in this area, and all five of the rhododendron varieties found in Turkey. When the rhododendrons bloom, they give off such a beautiful smell — and the bees that feed on them make delicious honey,” Karahan, a bakery owner in the nearby town of Artvin and the tireless president of the Green Artvin Association, told mongabay.com.

She was quick to point out, proudly, that the Artvin area is home to Turkey’s first and only UNESCO-recognized biosphere reserve, the Camili Biosphere Reserve. “But the mining companies only care about what’s under the ground, not what’s on top of it.”

This mountain in Artvin lies within the boundaries of both an area designated for tourism and an area designated for mining. Photo: Jennifer Hattam.

Mines, dams, and access roads have already scarred much of the landscape around Artvin, where activists rallied last year to keep a gold mine from being constructed in Cerattepe, part of the mountainous recreational area. “None of these projects could have happened before the 1980s, but if people keep leaving the villages, it will be even easier to build them,” said Karahan.

Like other parts of Turkey, the Black Sea region that includes Artvin has experienced mass migration from rural areas to urban ones since the middle of the twentieth century, with the pace of demographic change quickening from the 1980s onward. Reduced government support for agriculture and livestock husbandry encouraged the move to cities, as did the economic growth created by the opening of land borders to nearby Georgia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Activists say development of hydropower plants and extractive industries in the region’s villages and valleys has also created a vicious cycle in which construction pushes people out, leaving fewer residents to protest future development.

“In a lot of these villages, the young people have gone off to study and work, leaving only the older people. They don’t have a lot of money, and may be afraid to go up against the companies and the government [that backs them],” said Murat Deha Boduroğlu, an Istanbul-based attorney who does pro bono work representing Black Sea villagers fighting environmentally damaging projects.

Turkey’s governing Justice and Development Party (AKP), in power since 2002, lost its parliamentary majority in elections held 7 June. The coming months are expected to bring either the formation of a coalition government, or a call for a new election. Whether this will temper the AKP’s ability to continue its longstanding support for mining and hydroelectric interests in rural areas remains unclear.

In any case, the out-migration that has left many Black Sea villages vulnerable is also helping give others a broader base of support, and a louder voice, in some of Turkey’s largest cities.

“People who have moved to Istanbul and other big, crowded cities still go back to their villages for holidays and often hold onto a desire to keep these places green, and intact, and somewhat productive agriculturally for their retirement years,” Sinan Erensu, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Minnesota studying the resistance to energy development in Turkey’s Black Sea region, told mongabay.com. “These people can become defenders of what they call their yaşam alanı, or ‘life spaces.'”

Artvin’s fight against the gold mine was bolstered by just such people, many originally from the nearby mining town of Murgul, where the gold dug up in Artvin would have been processed using a method called heap leaching that creates toxic pools of cyanide waste.

“There were solidarity marches in Istanbul, Bursa, İzmit, and other Turkish cities where people have migrated to from Murgul,” said Alper Şeyhoğlu of the Murgul No to Cyanide Platform, an advocacy group that helped organize local demonstrations in September. Three thousand people participated, pulling their children out of school and closing up their shops for the day in protest.

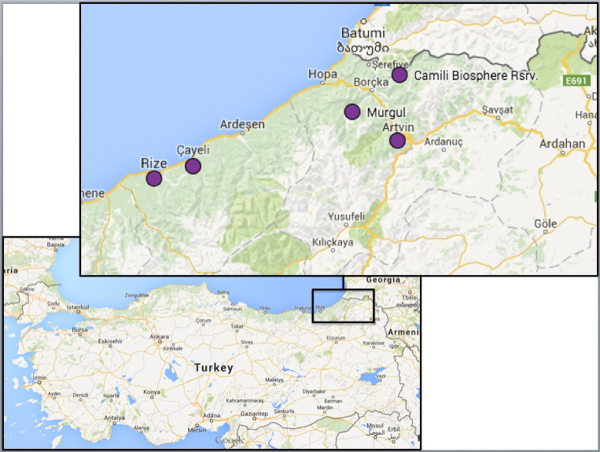

Map of Turkey. Map credit: Google Maps. Click to enlarge.

“People don’t lose their connection to their valley when they move away,” said Ahmet Ali Kork, an electrical engineer from Çayeli, a Black Sea village in the steep, tea-growing Senoz Valley, where Turkey’s little-known Hemşin culture, an ethnic group with Armenian origins, still thrives. When locals rose up against the building of stone quarries and hydropower dams, Kork said, “Senoz people in Istanbul also fought to block this assault on nature.”

New activist networks within the region and throughout the country are also helping connect often-isolated Black Sea residents with each other, and with outside support. Attorney Boduroğlu and his law partner, Alp Tekin Ocak, are part of the Ecology Collective, a group of lawyers, journalists, social scientists, and other professionals who provide free legal assistance and technical support to local communities around Turkey and help them get publicity for their causes.

“It’s been hard for a strong environmental resistance to develop in Turkey, because no single site is an epicenter, but we’re trying to help join up the different efforts,” Doğu Eroğlu, a journalist member of the collective, told mongabay.com.

In recent years, many environmental groups have also started to seek common cause. Activists in Istanbul, Ankara, and other large cities organized bus trips to fortify the ranks of olive growers fighting now-cancelled plans to build a coal-fired power plant in the Aegean village of Yırca, and to show support to Hasankeyf, an ancient town in Southeastern Turkey threatened with submergence by a massive dam.

One group that started out protesting individual hydropower projects around the Black Sea city of Rize has emerged as a strong voice for environmental protection across the region.

A protest in Istanbul organized by the Brotherhood of the Rivers Platform against a planned nuclear power plant in the Black Sea town of Sinop and various hydropower plants elsewhere in the Black Sea region. The banner reads: “No to nuclear and hydropower.” Photo: Brotherhood of the Rivers Platform/Fuat Yüksek.

“The first big battle against hydropower in the region was in the 1990s; by the mid-2000s these projects were starting in every valley,” Ömer Şan, a Rize-based journalist and spokesman for the advocacy group Brotherhood of the Rivers Platform, told mongabay.com. Folding up fresh-off-the-presses copies of his small, local newspaper and affixing mailing labels to them in his one-room office in downtown Rize, Şan explained how the steepness of the land and the level of rainfall in Turkey’s Black Sea region makes it a prime target for run-of-the-river hydropower generation.

“We kept hearing about these projects being initiated everywhere, so we started calling people up to share information and ask if they needed any help,” he said. Eventually, the Brotherhood developed into a regional umbrella organization, perhaps the first of its kind in Turkey. Its members — all volunteers — create expert reports, provide legal help, and offer media expertise to communities fighting to preserve their natural environment and way of life.

These fights can be lengthy, and permanent victory hard to declare. The Green Artvin Association has been working to keep mining out of Cerattepe for 20 years. Its legal case against the gold-mining operation bore fruit in January when an administrative court in Rize cancelled the Environment Ministry’s approval of the environmental impact assessment for the project. Artvin and Murgul celebrated the win with a traditional Black Sea horon, a type of circle folk dance, in the streets.

“We showed Turkey that there can be a success against a company as big as Cengiz,” said Murgul activist Şeyhoğlu. Turkish conglomerate Cengiz Holding, which owns major mining operations in the Artvin area, has close ties to the government and a role in controversial projects around the country, from a third airport under construction in Istanbul to a planned nuclear power plant on the Mediterranean coast.

But with the rich deposits of gold, copper, and other valuable metals and minerals in the Artvin area, few expect that mining companies have given up for good. “The case we won was appealed to a high court; we’re still waiting for a decision from them,” said Karahan. “If we stop our resistance, Artvin will be no more.”