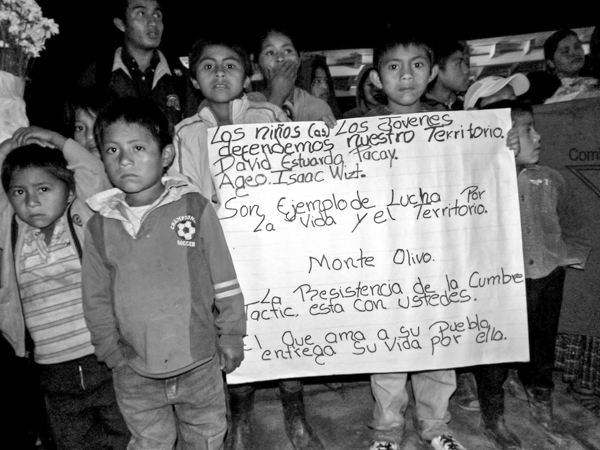

Children carry a banner commemorating two children allegedly killed in 2013 by an employee of the company that owns the Santa Rita dam. The banner reads in part "They are examples of the struggle for life and land." Photo credit: Peoples’ Council of Tezulutlán.

Children carry a banner commemorating two children allegedly killed in 2013 by an employee of the company that owns the Santa Rita dam. The banner reads in part "They are examples of the struggle for life and land." Photo credit: Peoples’ Council of Tezulutlán.

A hydropower project planned on Guatemala’s Icbolay River has resulted in major human rights abuses, advocacy groups are charging.

The 24-megawatt Santa Rita dam would be located in the country’s central Alta Verapaz department. It is backed by the World Bank and several European banks, as well as the Guatemalan government. In spite of the alleged abuses, the dam’s owner has been granted approval by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) to earn carbon offset credits for the electricity the dam would generate. The credits could be traded under the European Union’s Emission Trading System. The project, in a nation currently wracked by political upheaval over government corruption, is one of several prompting efforts to reform the CDM.

Ever since construction of the Santa Rita dam was assigned to a Guatemalan company called Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita, S.A in 2008, it has been marred by controversies, and the construction of the dam is currently on hold. Human rights groups say the dam was approved despite the lack of free, prior, and informed consent of the Maya Q’eqchi´ and Poqomchí indigenous communities that reside in the area where it would be built. The rights groups contend that the construction of the dam will take away the communities’ lands and limit their access to the Icbolay River, which they rely on for drinking water and agriculture, while giving nothing in return. They say most of the communities do not have access to electricity, but the project will not bring it to them, instead feeding power into the national grid.

“In the region, the company is the biggest violator of both collective and individual human rights of people,” Maximo Ba Tiul, a spokesman for the Peoples’ Council of Tezulutlán, an indigenous activist group in Guatemala resisting the dam, told mongabay.com.

Peaceful protests and blockades by the communities have ended in violence, including several murders, forced evictions, and the unlawful imprisonment of community leaders, the Tiul’s group and others allege.

In 2013, for instance, an employee of Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita, S.A, which owns the project, shot and killed two Mayan children, aged 11 and 13 years, local activists alleged according to news reports. The assailant was reportedly looking for the children’s uncle, David Chen, an activist fighting the Santa Rita dam who had previously escaped a kidnapping attempt.

The children’s murder created uproar. According to news reports, 17 local organizations issued a joint press statement on the day of the murders holding the “Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita S.A Company and the government responsible for violating the rights of the population and provoking conflict in the area.”

Later, in April 2014, a local landowner and his security guards with links to Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita, S.A. opened fire on indigenous community members participating in a religious ceremony, killing one person and injuring five, according to rights groups. A few months later, in August, over 1,500 police officers entered the region, unleashing a tear-gas assault on about 200 indigenous families gathered in a peaceful protest against the dam. Three women and two men were also captured illegally and humiliated by the officers, according to a letter sent in October by the more than two-dozen local and international human rights organizations to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples.

A sign demands justice at a funeral procession for three indigenous people allegedly killed during an operation by the Guatemalan government in August 2014. Photo credit: Peoples’ Council of Tezulutlán. |

Clashes of these kinds have claimed the lives of 7 people and injured 70, according to the letter. In addition, 30 people have been illegally arrested, 30 houses have been burnt to the ground, and several families have been forced to flee their homes and seek refuge elsewhere, the letter stated.

Dams, mines, and other projects with heavy environmental footprints and government backing are getting renewed scrutiny and public attention in Guatemala, where allegations of violence and intimidation related to new infrastructure projects are widespread. In recent weeks the country has seen massive protests over a wave of corruption scandals that led to the resignation of numerous top government officials, including Vice President Roxana Baldetti, Minister of the Environment and Natural Resources Michelle Martínez, Minister of Energy and Mines Edwin Rodas, and Minister of the Interior Mauricio López Bonilla.

Sloppy consultation process

The Peoples’ Council of Tezulutlán and other rights groups stress that the government and the UN’s CDM body have approved construction of the Santa Rita dam without properly consulting local communities.

In 2014, long after allegations of human rights abuse began to emerge, the UN’s CDM board registered the hydropower plant, giving the project a green aura and allowing Hidroeléctrica Santa Rita, S.A to earn carbon offset credits tradable in Europe’s carbon market that would enable countries to reduce their carbon emissions to achieve their emissions targets.

The hydropower dam is expected to cost about $67 million, according to its Project Design Document. The project is supported by a private equity fund that has investment from the World Bank and four European development institutions — the German Investment Corporation, the Netherlands Development Finance Company, the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation, and the Swiss Investment Fund for Emerging Markets — according to Carbon Market Watch, a Belgium-based watchdog organization that analyzes carbon markets.

CDM rules require that project officials consult the affected local communities and take their comments into consideration. But in the case of the Santa Rita dam, public consultation was sloppy, according to human rights groups.

In a May 2014 letter sent to the CDM Executive Board, the Peoples´ Council of Tezulutlán asserted that the project’s official public consultation process communicated only with selected community members, most of who already supported the project. Moreover, the consultation involved only nine of the more than 30 communities that would actually be affected by the Santa Rita Hydroelectric project, the group noted. At community meetings, 24 of these communities rejected the project, according to the letter.

The CDM Executive Board reviewed the allegations laid out by the local stakeholder groups. In fact, according to Carbon Market Watch, this was the first time the CDM formally reviewed a project based on allegations that local consultation was inappropriately conducted. However, in a response letter dated 5 June 2014, the Executive Board concluded that the project was "in compliance with the applicable CDM requirements, including the local stakeholder consultation process.”

Eva Filzmoser, the director of Carbon Market Watch, called CDM’s decision to take local consultation seriously a "milestone." But she told mongabay.com that the CDM board did not explain how they had gone about reviewing the grievances. For instance, correspondence from the CDM board noted that the project complied with all CDM requirements because the designated national authority had assured the board that was the case, she said. The CDM board appears to have based its approval solely on correspondence with officials associated with the project, as Carbon Market Watch and the other human rights groups wrote in their October letter to the UN Special Rapporteur.

A lack of consultation for large environmental projects is common in Guatemala, advocates say. When Dinah Shelton, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples at the time, visited the country in 2013, she expressed concern in a press statement that “the current licenses for mining and hydroelectric plants were granted without the State having implemented prior, free, and informed consultation with affected indigenous communities, as it is obligated to do under international treaties signed by Guatemala.”

A wider problem with green-stamped projects

But Santa Rita is not an isolated case of a green-stamped project embroiled in human rights violations. A number of other CDM-approved power-generating projects in Guatemala and other countries have been implicated as well, according to a 2013 compilation of case studies by Carbon Market Watch.

For example, at least two other CDM-registered hydroelectric projects in Guatemala violated human rights by failing to obtain informed consent from affected indigenous communities and by using violence and forceful evictions against protesting communities, according to rights groups and media reports. These include the 85-megawatt Palo Viejo dam in the municipality of San Juan Cotzal and the 94-megawatt Xacbal dam in the municipality of Chajul.

A month after asserting the Santa Rita dam had followed local stakeholder consultation rules appropriately, the CDM Board agreed to amend those rules at a meeting of its executive board in July 2014. The change followed mounting criticism over flawed consultation processes in many CDM-approved projects. The new amendments re-defined the scope of local stakeholder consultations — for example, the minimum group of stakeholders that need to be involved in consultations, how the consultations would be conducted, and what information must be made available to the stakeholders.

“This is in principle a great step forward,” Filzmoser said. “Unfortunately, it disregards the need for a compliance mechanism, or an investigation panel in cases where national or international obligations are not respected.”

“To date, the CDM does not have a grievance mechanism, something that we hope will change as part of the CDM reform as part of the upcoming UNFCCC negotiations in Bonn, Germany, starting on 1 June,” Filzmoser added, referring to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations.

With business-as-usual in Guatemala disrupted by government and social upheaval and the CDM’s rules in flux, communities in Alta Verapaz may have a new window of opportunity in their fight for a definitive cancelation of the Santa Rita dam.