Sankuru Nature Reserve draws ire from some conservationists, other protections planned

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are often touted by scientists as a peace-loving great ape species, opting to solve social conflicts through sex rather than aggression. But their only refuge, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is a country torn by war for decades.

Amid the conflict, bonobos continue to survive in forests south of the Congo River in the DRC, albeit under constant threat of hunting, loss of habitat and the growing demands of an increasing human population. It is thus no wonder that their numbers have been declining across most of their historic range. Protecting bonobos is not easy, either, especially since these apes are elusive and difficult to survey.

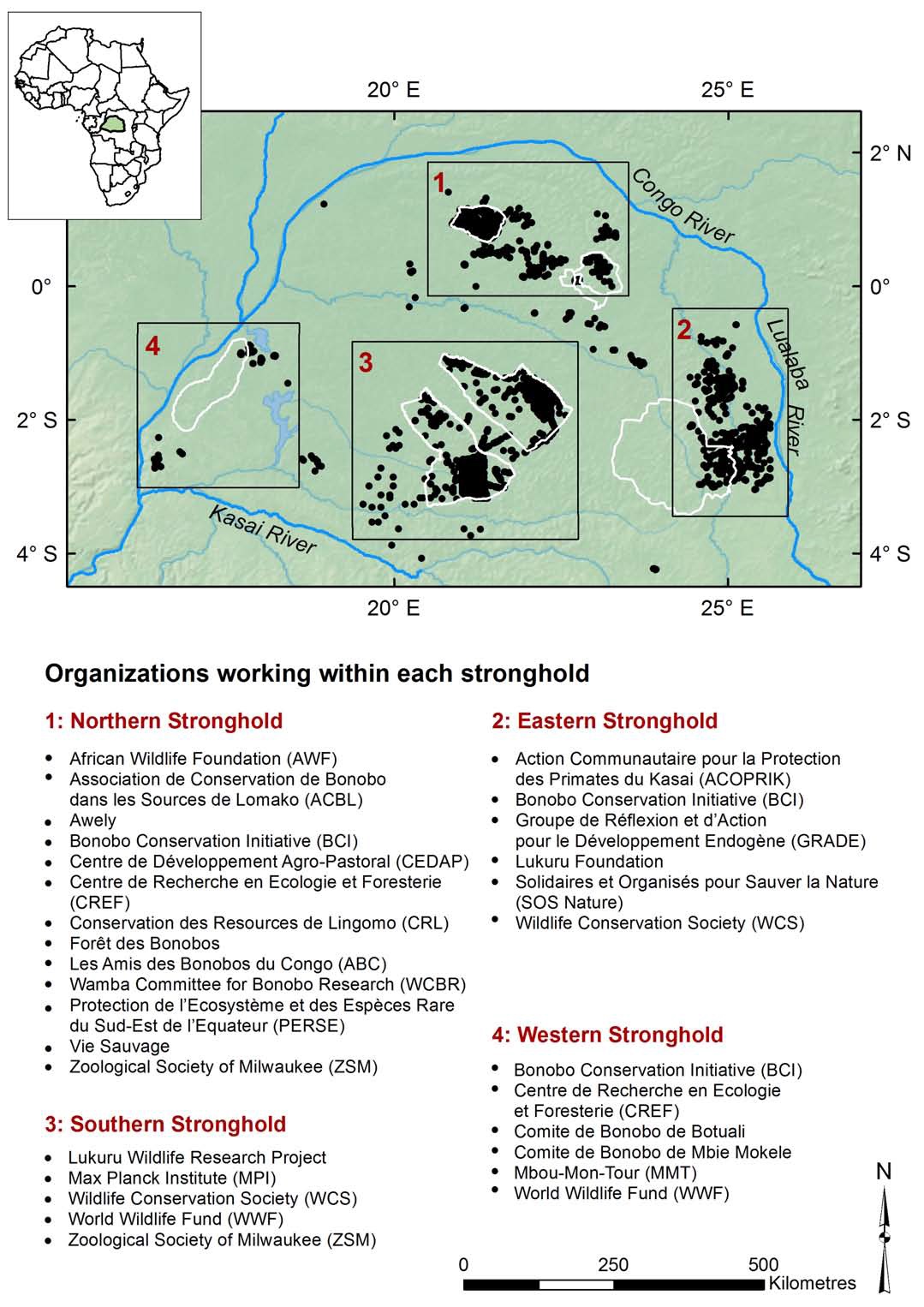

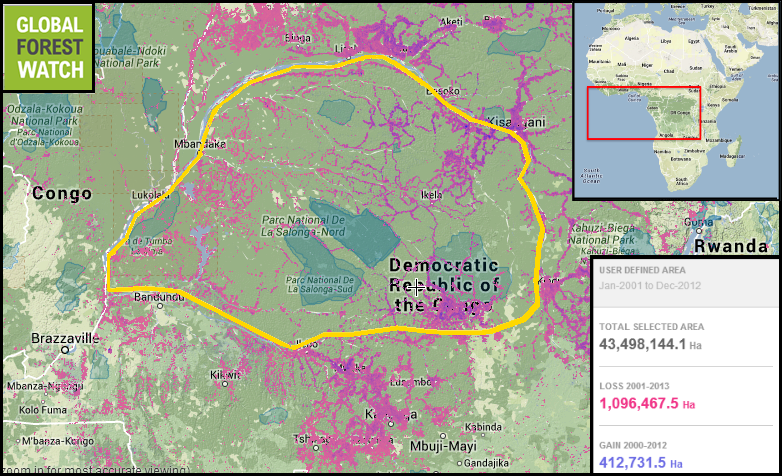

Approximate bonobo range showing tree cover loss from Jan 2001 to Dec 2012. Range adopted from Hickey et al., 2012, and map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Despite the paucity of information, conservationists in the DRC have, over the years, tried and tested different conservation strategies to protect the last of the bonobos. And some of these strategies have invited considerable debate.

Clash of conservation approaches

Sankuru Nature Reserve (SNR), established in 2007, has been one such topic of debate (read Part I, Part II and Part III for more details on the reserve). The park was set up to serve two main purposes: protecting bonobos, and protecting the forest.

But has it achieved what it set out in its goals? Some conservationists seem to think otherwise.

Recent figures by Global Forest Watch show that SNR has lost over 36,000 hectares of forest to date. In addition, according to a report by IUCN’s Primate Specialist Group, two independent surveys in the region found that bonobos were present in only 17 percent of SNR, in the east, while the south-central and southwest areas of SNR had none.

Moreover, SNR has over 78,000 human inhabitants, signs of hunting are widespread, and over half of the reserve is secondary or degraded forest, the report states.

“The two main objectives for creating the Sankuru Reserve failed from the beginning,” Jo Thompson, bonobo-expert and executive director of the Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation, told mongabay.com. “They were not realistic when made, and were designed without facts from the ground.”

Another point of contention that surrounds Sankuru Reserve is the lack of transparency at the time of its creation.

“When the reserve was created in 2007, no faunal surveys were carried out and the local communities were not consulted,” Ashley Vosper, a consultant formerly with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), told mongabay.com. Vosper was part of the WCS team that surveyed the western and southern parts of SNR in 2009, and found no evidence of elephants or other large mammals. In fact, according to Vosper, the local communities seemed to claim that elephants had disappeared from the area more than 20 years ago.

Bonobos caught on camera in the proposed Lomami National Park. Courtesy of the TL2 project.

Thompson adds that once the establishment of SNR was announced, several conservation organizations working in DRC requested documentation that could provide details about the reserve. But they received none. The development of SNR seems to have flown under the radar of DRC’s conservation community, suddenly appearing on the “protected area map” of DRC one day.

“There was no chain of paperwork to document the process of creating the reserve, and no funding structure was shared to support the process of creating the reserve,” she added.

Terese Hart, Director of the TL2 project that operates in a region adjacent to Sankuru Nature Reserve in the east, said that they were particularly surprised by the lack of on-ground conservation presence in Sankuru.

“Although we work in an area of very high biodiversity in Lomami-Sankuru border, we have had no interaction with Sankuru personnel on-ground at all,” she told mongabay.com.

A bonobo walks up to the termitarium. A baby sits astride its mother behind some leaves. Courtesy of the TL2 project.

The Sankuru approach

So how was Sankuru Nature Reserve created in the first place?

According to Sally Coxe of Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), “the conception of the Sankuru Reserve began in 2001 with a local initiative led by the Action Communautaire pour les Primates du Kasai (ACOPRIK), specifically to combat the rising trade in primate bushmeat.”

In 2005, BCI and ACOPRIK formed a partnership. Following this, they worked with the local communities in Sankuru, assessing their attitudes and beliefs, and carried out biological surveys of the region in partnership with the DRC government’s national Centre de Recherche en Ecologie et Foresterie (CREF), Coxe said. Their surveys found evidence of bonobos, okapi, elephants and other wildlife in the SNR region.

However, during subsequent surveys by independent conservation organizations, evidence of large mammals across most of SNR was almost non-existent, except in the east.

It appears that BCI, CREF, and ACOPRIK had initially proposed an approximately 7,000-10,000-square kilometer, community-based nature reserve covering this eastern part of SNR. This was based on surveys that determined areas that seemed to have higher biodiversity and intact forest cover, Coxe said. But eventually, the reserve area more than doubled.

“After further analysis and deliberation with local representatives, the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN) decided to enlarge the area to include the broader Sankuru territory, in order to protect the important watershed there, to sequester carbon, as well as to protect wildlife,” she added. “To withhold this protection of this watershed, just because portions of the area are degraded, under threat, and do not have the same abundance of species as elsewhere, for example the eastern section of the reserve, would be shortsighted, at the least.”

A young adult male bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus). Courtesy of the TL2 project.

However, Coxe acknowledged that poaching and habitat loss due to human presence inside Sankuru Reserve is indeed a threat to bonobos. Despite this, “including the people the threatened land has belonged to, and partnering with them, promises better future for that land,” she added.

Vosper disagrees. “Working with local communities would really help in saving the bonobos. But it here it seems to me that the park is being given to the communities so that they can carry on hunting as before,” he said. “This does not make sense to me.”

Gay Reinartz, director of the Bonobo and Congolese Biodiversity Initiative (BCBI), also points out that establishing a reserve as big as SNR is not a guarantee of its protection.

“Poaching and lack of law enforcement is a threat to bonobos (and all forms of wildlife) across all reserves and protected areas, even in national parks,” she told mongabay.com. “The challenges are especially great when a reserve such as Sankuru has within it or near it large and growing human populations, roads, and established areas of active agriculture. These areas are much more vulnerable to hunters and agricultural encroachment, and thus deforestation and fragmentation.”

Camera trap photo of a lesula (Cercopithecus lomamiensis), a new monkey species discovered in the proposed Lomami National Park. Photo courtesy of the TL2 project.

The Lomami approach

In sharp contrast to SNR, the proposed Lomami National Park (LNP) is almost devoid of human settlements. It is a vast expanse of mostly intact tropical rainforest that lies to the east of Sankuru Reserve, and covers approximately 9,000 square kilometers (3,475 square miles).

Lomami National Park has been carved out of what conservationists call the TL2 landscape, named after the three large rivers it encompasses, Tshuapa – Lomami – Lualaba (from west to east). In 2007, Terese and her husband, John Hart, began surveying the unexplored TL2 landscape with their Congolese team. Several years of persistent and systematic surveys revealed more than 5,000 bonobos lived inside TL2, in addition to elephants, okapi and other wildlife. The team also discovered a new monkey called the lesula (Cercopithecus lomamiensis) during one of their surveys.

Additionally, when the TL2 project team surveyed the landscape for signs of human activities, they found that logging and mining was limited. It was hunting that was the main cause for concern.

“Our concentration in Lomami National Park has been anti-hunting patrols,” Hart told mongabay.com. “The bushmeat market is still very profitable. So there is a strong push to maintain it, and the only source of bushmeat in this region is Lomami National Park.”

Elephants with muddy knees amble by night around a clearing in the northern TL2 area, site of the proposed Lomami National Park. Courtesy of the TL2 project.

Despite some resistance from the bushmeat lobby, the Harts now have a lot of support from the communities around LNP. “It has been a long process,” Hart said.

The team established a bushmeat monitoring network, experimented with livelihood alternatives to bushmeat hunting, introduced new crop varieties to farmers, involved the community in most of their endeavors, and trained wildlife agents for better enforcement of wildlife laws.

For most of the DRC bonobo conservationists, LNP has great potential to protect the last of these great apes.

“First, the region is not densely populated,” Reinartz said. “Secondly, the park has been planned over the past decade with critical stakeholders to help provide both local communities and national authorities the capacity to protect the area. Bonobo strongholds have been identified within the reserve, and targeted research and monitoring programs are already underway that can ostensibly measure the impact of conservation activities.”

Poacher caught “red-handed” hunting by a camera trap. Courtesy of the TL2 project.

Bonobos elsewhere

Several other protected areas in DRC harbor sizeable bonobo populations. These include the Salonga National Park, which has almost 40 percent of DRC’s wild bonobo population, the Lomako-Yokokala Faunal Reserve, the Luo Scientific, Iyondji Community, and Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve.

However, these wild bonobos do not occur contiguously across their range, and neither are they continuous within the limits of a protected area, according to Thompson. “In my opinion, the threats to bonobos, as they are today, cannot be reduced or eliminated at any site sufficiently enough to allow the bonobo populations to increase in numbers. We can only work to slow the decline.”

One way to slow this decline, conservationists agree, is for conservation NGOs to come together in their cause to save the last of the bonobos. “They need to share ideas, and have a more united front,” said Vosper.

>

Related articles

Invasion of the oil palm: western Africa’s native son returns, threatening great apes

(07/28/2014) As palm oil producers increasingly look to Africa’s tropical forests as suitable candidates for their next plantations, primate scientists are sounding the alarm about the destruction of ape habitat that can go hand in hand with oil palm expansion. A recent study sought to take those warnings a step further by quantifying the overlap in suitable oil palm land with current ape habitat.

Setting the stage: theater troupe revives tradition to promote conservation in DRC

(07/22/2014) Two years ago, environmental artist Roger Peet set off to the Democratic Republic of Congo to support the new Lomami National Park with bandanas that he designed. This time, Peet is back in Congo to carry out a conservation theater project in remote villages near the proposed Lomami National Park.

(07/18/2014) Sankuru Nature Reserve was established in 2007 primarily for bonobo protection. The largest continuous protected great ape habitat in the world, Sankuru is still losing large swaths of forests to burning and other activities, primarily along roads that transect the center of the reserve. However, hope exists, both from human efforts – and from the apes themselves.

Poaching, fires, farming pervade: protecting bonobos ‘an enormous challenge’ (Part II)

(07/17/2014) Sankuru Nature Reserve in the DRC was established in 2007 to safeguard the 29,000 to 50,000 bonobos that remain in existence. However, while touted as the largest swath of protected continuous great ape habitat in the world, the reserve is still losing thousands of hectares of forest every year. Burning, bushmeat hunting, and agricultural expansion are taking a large toll on the endangered great ape.

Will the last ape found be the first to go? Bonobos’ biggest refuge under threat (Part I)

(07/16/2014) Bonobos have been declining sharply over the past few decades. In response, several non-profit organizations teamed up with governmental agencies in the DRC to create Sankuru Nature Reserve, a massive protected area in the midst of bonobo habitat. However, the reserve is not safe from deforestation, and has lost more than one percent of its forest cover in less than a decade.

Bonobos: the Congo Basin’s great gardeners

(12/11/2013) The survival of primary forests depends on many overlapping interactions. Among these interactions include tropical gardeners, like the bonobo (Pan pansicus) in the Congo Basin, according to a new study in the Journal of Tropical Ecology. Bonobos are known as a keystone species, vital to the diversification and existence of their forests.

28 percent of potential bonobo habitat remains suitable

(11/27/2013) Only 27.5 percent of potential bonobo habitat is still suitable for the African great ape, according to the most comprehensive study of species’ range yet appearing in Biodiversity Conservation. ‘Bonobos are only found in lowland rainforest south of the sweeping arch of the Congo River, west of the Lualaba River, and north of the Kasai River,’ lead author Jena Hickey with Cornell told mongabay.com. ‘Our model identified 28 percent of that range as suitable for bonobos. This species of ape could use much more of its range if it weren’t for the habitat loss and forest fragmentation that gives poachers easier access to illegally hunt bonobos.’

Remarkable new monkey discovered in remote Congo rainforest

(09/12/2012) In a massive, wildlife-rich, and largely unexplored rainforest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), researchers have made an astounding discovery: a new monkey species, known to locals as the ‘lesula’. The new primate, which is described in a paper in the open access PLoS ONE journal, was first noticed by scientist and explorer, John Hart, in 2007. John, along with his wife Terese, run the TL2 project, so named for its aim to create a park within three river systems: the Tshuapa, Lomami and the Lualaba (i.e. TL2), a region home to bonobos, okapi, forest elephants, Congo peacock, as well as the newly-described lesula.