Orphaned Orangutan in Central Kalimantan. Photos by Rhett A. Butler.

In December 2007, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono launched Indonesia’s Strategy and Action Plan for National Conservation of Orangutans. Quoting the president from his speech, “this will serve as a blueprint for our efforts to save some of our most exotic but endangered wildlife.” Furthermore, the president said that “the Orangutan action plan formally endorses Indonesia’s commitment to orangutan conservation as expressed in 2005 when Indonesia signed the Kinshasa Declaration on the Protection of Great Apes in the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

And a final quote: “A key understanding that stems from this Action Plan is that to save orangutans, we must save the forests. And by saving, regenerating, and sustainably managing forests, we are also doing our part in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions, while contributing to sustainable economic development of Indonesia. Successful orangutan conservation is the symbol of responsible management of the earth’s resources.”

Excellent stuff. Finally a ray of hope for Indonesia’s endangered species.

Bornean orangutan.

We are now over six years into the 10 years action plan, so signs of progress should be easy to find. The action plan commits Indonesia to stabilizing all wild populations by 2017. With habitat loss and hunting being the main threats, this simply means that all remaining wild orangutan populations should either be incorporated in formally protected areas or other compatible land uses, such as sustainably managed timber concessions, and that conservation laws should be enforced.

Unfortunately there is almost no sign of such progress. In the six years since the plan’s launch, not a single orangutan population has experienced a land use change that will make it any more likely to survive. No new protected areas have been set up for orangutan conservation. And few if any plantation licenses have been canceled because of the presence of orangutans, and the area subsequently turned into permanent forest estate.

In fact, the opposite has happened. Vast areas of orangutan habitat have been converted to oil palm. The Tripa swamps in Aceh are a prime example of disastrous conservation management and the total irrelevance of Indonesia’s stated commitment to orangutan conservation.

But other examples abound. An example from Kalimantan is the situation around the Danau Sentarum National Park. In 2007, the orangutan population here was estimated at 500 individuals in 109,000 hectares of deep peat swamp forest. But as you read this, excavators are taking down trees and clearing peat land for planting oil palms in those same swamp forests. Give it a few more years, and most of those 500 orangutans will be gone, starved to death, caught and stuck in a cage, clubbed over the head, or set on fire, as sometimes happens.

A cynical interpretation would be that a population of zero animals is stable after all, exactly as prescribed by the action plan, but I doubt that this is what the president had in mind in 2007.

Now, to be upfront, I was heavily involved in the development of Indonesia’s orangutan action plan. Indonesia, we thought, urgently needed some kind of government-endorsed strategy for the conservation of orangutans and many other threatened species. The idea was to develop the national strategy, then translate this into local strategies at province and district level, ultimately leading to recommended land use changes that are compatible with conservation, and allocation of sufficiently large budgets and institutional support to ensure that those areas are effectively managed.

Step one was taken, and a bit of step two, but that was pretty much it. I would be very interested to know what further steps are envisaged by the Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation (PHKA) for implementing the action plan. How much is the present budget allocation and how many staff are assigned to the process? Also, what are the annual targets and milestones, and what corrective actions are taken when it is clear that those targets are missed?

Indonesia has an additional target for its key conservation species, including the orangutan. This prescribes a goal of 3 percent population growth, which is even more ambitious than stabilization. Surely, the authorities realize that this target is never going to be met.

After all, every year, several thousand orangutans in Kalimantan are killed in conflicts with people or for food, as reported in three recent studies in the journals PLOS ONE and Biological Conservation. Also, another study in PLOS ONE shows that Kalimantan lost 123,428 square kilometers (four times the area of the Netherlands) of lowland forest, i.e., prime orangutan habitat, between 1973 and 2010. Not all of this area was within the orangutan range, but with good orangutan habitat in Kalimantan containing up to 3 orangutans per square kilometer, it gives some indication of the scale of the population decline.

I may be misreading the numbers, but there seems to be a slight discrepancy between the loss of some 100,000 orangutans over 40 years, and the official goal to increase the population by 3 percent.

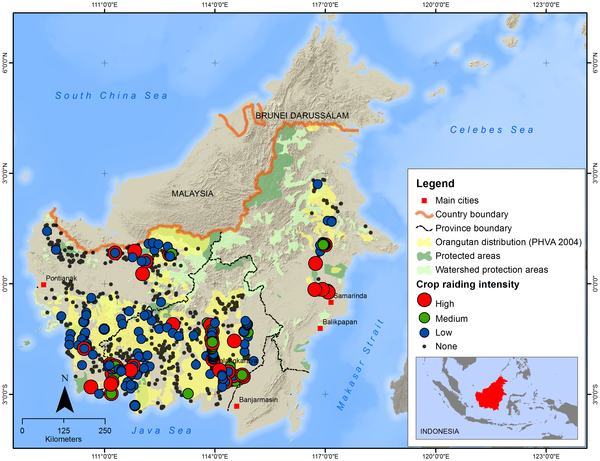

Crop raiding intensity in different villages across Kalimantan. High = reported conflict frequency every week; Medium = every month; Low = once a year or less frequently. Courtesy of PLoS One.

More than anything, Indonesia needs to realize what it is losing along with its orangutans. It is obviously not helping the country’s “green” image. More importantly, the present race to convert most lowland forest areas to plantations for the production of oil palm, rubber, timber, and pulp and paper, is going to generate large environmental costs that will mostly be borne by its rural and urban people.

For example, developing plantations on low-lying peats will inevitably lead to massive flooding after the peat has decomposed and the plantations are basically standing in semi-permanent lakes. No forest, no palm oil yields, no agriculture, no development.

Economic and social development is needed, but badly planned and implemented development primarily benefits the few who are lucky enough to own a plantation, mining lease, or timber concession, and those that help them in the process. The science and knowledge is there to guide development that ensures optimal economic, social, and environmental outcomes in the short and longer term. Our Borneo Futures initiative, for example, has plenty to say about this.

After all, section 14, article 33, of Indonesia’s constitution states that “the land and the waters as well as the natural riches therein are to be controlled by the state to be exploited to the greatest benefit of the people.” Also, “the organization of the national economy shall be based on economic democracy that upholds the principles of solidarity, efficiency along with fairness, sustainability, keeping the environment in perspective…”

This to me seems pretty clear about the responsibilities of the government.

I strongly urge Indonesia’s government institutions to uphold their national and international commitments and legal duties towards environmental protection and social fairness. I also urge them not to ignore the extensive scientific information on what works and what doesn’t in natural resource use, and based on that create and implement realistic policies for sustainable development and species conservation. Only thus will orangutans have any chance to survive in this country.

This op-ed originally appeared in the Jakarta Globe and has been reprinted here at the request of the author.