Illegal gold mining boat in Peru. Photo courtesy of Katy Ashe.

On the back of a partially functioning motorcycle I fly down miles of winding footpath at high-speed through the dense Amazon rainforest, the driver never able to see more than several feet ahead. Myriads of bizarre creatures lie camouflaged amongst the dense vines and lush foliage; flocks of parrots fly overhead in rainbows of color; a moss-covered three-toed sloth dangles from an overhanging branch; a troop of red howler monkeys rumble continuously in the background; leafcutter ants form miles of crawling highways across the forest floor. Even the hot, wet air feels alive.

Suddenly, the forest stops. Bone dry, dusty air burns my nostrils. The harsh equatorial sun, no longer filtered through layers of canopy and understory vegetation, beats down with full force. We are in a vast expanse of sandy desert, the tree line barely visible on the other side. The scar of deforestation reaches miles into the horizon.

An apocalyptic scene unfolds. Enormous muddy craters pepper the sandy terrain, filled with makeshift mining rigs. Illegal gold-miners in tattered clothing stand beside deafening rickety motors sucking earthen slurry through large hoses. Their faces are covered in motor oil and dirt, and they slump wearily from eighteen-hour days. Packs of men holler from the pits as I pass, misinterpreting me as a new prostitute for the camp.

This is the scene I pass through each morning on my way into the illegal gold-mining zones of Madre de Dios, Peru. Being a Stanford University graduate student in environmental engineering, I came to this region of the upper Amazon to study the mercury levels in the human population. These illegal mines use mercury to scavenge tiny flecks and pebbles of gold dust out of the slurry.

Mercury is being released in quantities of around 40 tons each year in this region. The detrimental toxin makes its way into the food, water and air that sustains the diverse peoples and animals found here. It is touching all life in this basin; poisoning even those that have no part in the mining industry and live nowhere near a mining zone. I was intent on determining the extent of mercury poisoning caused by the dramatically increasing mining activity.

Located in the western Amazon Basin, this is one of the most bio-diverse places on the planet. Home to some of the most unspoiled tracts of Amazon Rainforest remaining; it is a vibrant sanctuary of species. Unfortunately, it is rapidly disappearing as artisanal gold-mining has become a booming industry in the past several years. The global market price for gold has doubled in the past year alone, with skyrocketing prices fueled by fear during the global economy crisis.

Record high prices for gold have led to a boom in illegal gold mining in Peru; employing 100,000 people nationally and valued at $640 million a year. A poor migrant population, typically from the Peruvian highlands is flocking predominantly to this region of the Amazon Rainforest; there are approximately 300 new arrivals to the region each day, typically looking for work in gold mining. The government verifies that 2,000 square miles (over 500,000 hectares) of rainforest in Madre de Dios have been destroyed to date due to mining, but the environment groups on the ground claim the figure is actually threefold. The exact number is hard to pin down as the rate of deforestation has more than tripled in the last three years.

The mining zones are the Wild West in the worst possible way. The seemingly endless winding avenues of shanty towns sprawl out across the center of the mining zones; filled with makeshift abodes, brothels, restaurants, night clubs all constructed of black and blue tarps. Cities set up nearly overnight, and by morning the residents are hastily destroying one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet.

The immediate devastation is obvious: slash and burned forest, river channels with heaping rubble, sluiceways through which thousands of tons of Amazon soil are blasted with high-pressure water hoses.

Drunkards stumble down the main corridors at all hours of the day. Women sit out front of the brothels in plastic lawn chairs, lazily advertising their respective tents. Infants splash in the mercury-contaminated mining ponds as children throw rusted metal objects at each other. I grab a jagged, rusty, iron hoop from a toddler boy, only to be reprimanded by his mother for stealing his toy.

I come from a world where a broken mercury thermometer in my high school classroom spurred evacuation for the afternoon and extensive cleaning by people in hazmat suits. This child lives in a world where mercury is often viewed as an acceptable laxative–the incredible weight of mercury essentially pushes everything out of your digestive tract.

Mercury has been used in gold mining since the time of the Inca. But the releases that we are seeing now are devastating. Unfortunately, there is little knowledge in the mining camps about how to properly use mercury. They hold mercury in their bare hands and mix the toxic metal into buckets of dirt with their bare feet. Once they’ve recovered the mercury-gold mixture from the dirt, they heat the mercury off of the gold in a frying pan over an open flame, causing it to turn into a vapor form that is incredibly dangerous to breath. Local superstitions have led to rejection of mercury recycling technologies. The fact that mining this way is an illegal activity makes it nearly impossible to intervene with educational programs.

The health survey I used to interview hundreds of people living in the mining zones contained five simple questions that only required one word responses, yet they frequently elicited life stories.

A weary looking middle-aged man sat in the waiting room of the doctor’s office. His face was covered in the tan dust of the mining camps and his hands were chapped from long hours of work with heavy machinery. The dark circles under his eyes suggested he just got off from a night shift. When I approached him asking if he would care to participate in my study about mercury contamination, he put on a sad half smile. He seemed dejected, but obliged out of pity. I asked him the regular questions, “What is your age? Where do you reside?”

Halfway through my questioning, he stopped me. “The next question you are going to ask me is about how often I eat fish,” he interjected as he grabbed my arm and looked in my eyes. He was right. Soon he was unraveling the long story of how he had ended up in the mining camps. He knew what I was going to ask because he was a professor of environmental studies in the highlands. In one course, he used to teach his students about the environmentally destructive nature of artisanal mining, but he was laid off along with many other professors when the budget at his institution was cut.

He began begging for forgiveness. He explained that he looked for serious work for years before resorting to mining, but eventually followed the promise of at least temporary financial security. “You have to understand,” he pleaded, “There was nothing left for me to do.” I desperately tried to stop his apology.

Frequently, the people I interviewed would ask for my forgiveness or help. Women would beg me to bring medicine to their children. Prostitutes, usually younger than me, would demand to know why they should trust me, a stranger, after all that has happened to them.

“Would you like to participate in my study?” I asked a pack of a dozen young girls sitting outside of a sizeable brothel tent. They all roared with giggling and chattering at my accent. “Are you from the United States?” one of them asked. “Yes,” I replied and repeated the question—would they like to participate in my study? All of them were under eighteen, making them too young to participate in my study.

The contrast was crushing. My research guidelines prohibited me from allowing them to join my study with the intent of protecting minors. Yet, here they were, cast into a life of prostitution. They were disappointed they couldn’t help me out and demanded that I stay and chat for a while.

The girls had ended up in the camp after receiving a tip that there were restaurants looking for waitresses and willing to pay top-dollar. Friends from the highlands, they immediately jumped on a bus together and came down to the rainforest. What they found was not what they were expecting: the mining camp restaurants served food for only a few hours a day—the rest of the time, it was the girls themselves who were on the menu. Literally at the end of the road, and without the money to return home, the girls soon became trapped in prostitution.

“We are making a lot of money,” one girl said as she looked down at her shoes in embarrassment. Another chimed in, “It’s not like we are going to stay here for more than a month.” The other girls echoed with unconvincing agreement. The enormity of their situation weighed on their faces as they sunk into silence, replacing the bubbly flow of their earlier inquiries about my favorite musicians. They all scrawled their email addresses on a sheet of notebook paper and told me to stay in contact as I walked away.

Their story is not uncommon. It is estimated that 1,200 girls between 12 and 17 are, often forcibly, drafted into child prostitution. At least one third of the prostitutes in the camp are underage. If the other women in the mining camps are any indication, the girls will be in the camps much longer than they intended. Once in the camps it is extremely difficult to escape. Miners let pimps know if prostitutes try to escape and gun-slinging guards protect the only paths leaving the camps through the dense rainforest. Even when pimps aren’t holding the women against their will, many women don’t have the resources to escape.

Often, when I asked the women in the prostitution business how long they had been in the mining camp their eyes would widen at the realization of how much time had passed. One woman exclaimed, “two years?… I have been here two years!?,” before trailing into a long stretch of cursing and pulling at her hair in horror.

That was the common response that I heard from both miners and prostitutes after they told me how long they had been in the camps. “I never meant to stay here this long,” one miner said after he informed me that he had been in the camp for a year- and-a-half. Time in the endless sandpits is just a blur of monotonously long days with the 24-hour backdrop of whiny mining motors.

The average miner only spends two years in the camps. Just enough time to save up a bit of money to move back to their hometown and start small business or go back to school. Generally, they told me of very modest dreams. “I want a small restaurant,” one miner in his early twenties explained, “just a small place; I don’t need anything fancy… someplace safe, where I can have a family.” Many people told longingly about their villages in the mountains, where life was simpler, less dangerous in nearly every facet.

My research had landed in the middle of a fiery political debate. I was lucky to gain access to the illegal mining camps, to get past the armed guards and chained entries intended to keep all non-miners away. Every other researcher and journalist that I had heard of attempting the same had been shot. The only difference was that I had befriended a jovial local who was well-loved within the camps for providing advice to expecting mothers and ailing miners free-of-charge.

In the city plaza of Madre de Dios’ capitol, Puerto Maldonado, people shout through megaphones atop their lungs. Local indigenous tribes show up to scream, “we are being poisoned; you are taking our land.” Miners come the next day to violently refute, “Then why hasn’t mercury hurt me?,” or, “We need the jobs to survive.” A constant stream of increasingly futile shouting-matches echo through the region. The struggle between the two disparate viewpoints is unlikely to lead to solutions, but it lays bare the escalating desperation and human suffering at the heart of the problem.

Who is to blame for this catastrophe? The miners themselves have been the most popular and most convenient choice so far. Unfortunately, this stance has also been shown to be the least effective.

In 2010, the Peruvian Minister of the Environment placed heavy restrictions on mining in this region. This led to the unsuccessful approach of stricter permitting and Peruvian military troops attempting forced removal of miners. But even if some miners are successfully sent away, thousands are on their way from the highlands to fill their shoes. A recent study shows that deforestation in this area is increasing even faster than before.

As long as there is mercury available at a low enough price, people will find a way to mine. Gold brings in enough money and the people in the highlands are sufficiently poor to keep this industry booming, illegal or not. But if the supplies of poverty and greed are inexhaustible, the supply of mercury need not be.

Peru imports nearly all of the mercury used in the country, some 280 tons in 2010, and over 95 percent of that is used directly in artisanal mining. That makes an easily accessible tap that the national government could choose to turn off. Yet, even if Peru makes an effective policy that stops illegal gold mining in its tracks, what will happen to the over 30,000 gold-miners that will be out on their luck once again?

There is no simple answer to this problem. Yet, on the path to finding a practical solution one thing is devastatingly clear, the era of finger-point and easy targets needs to end.

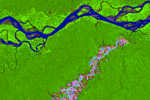

Aerial view of scarring from gold mines in the Peruvian Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Related articles

Peruvian authorities raid illegal gold mining operations

(11/07/2011) Peru’s Defense Ministry destroyed at least 75 illegal dredges and seized 15 vehicles from gold miners operating illegally in one of the most biodiverse parts of the Amazon rainforest.

High gold price triggers rainforest devastation in Peru

(10/11/2011) As the price of gold inches upward on international markets, a dead zone is spreading across the southern Peruvian rain forest. Tourists flying to Manu or Tambopata, the crown jewels of the country’s Amazonian parks, get a jarring view of a muddy, cratered moonscape … and then another … and another in what the country boasts is its capital of biodiversity. While alluvial gold mining in the Amazon is probably older than the Incas, miners using motorized suction equipment, huge floating dredges and backhoes are plowing through the landscape on an unprecedented scale, leaving treeless scars visible from outer space. Sources close to the Peruvian Environment Ministry say the government is considering declaring an environmental emergency in the region, but emergency measures passed two years ago were not enough to contain the destruction, and some observers doubt that a new decree would have any more impact.

Demand for gold pushing deforestation in Peruvian Amazon

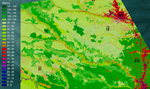

(04/19/2011) Deforestation is on the rise in Peru’s Madre de Dios region from illegal, small-scale, and dangerous gold mining. In some areas forest loss has increased up to six times. But the loss of forest is only the beginning; the unregulated mining is likely leaching mercury into the air, soil, and water, contaminating the region and imperiling its people. Using satellite imagery from NASA, researchers were able to follow rising deforestation due to artisanal gold mining in Peru. According the study, published in PLoS ONE, Two large mining sites saw the loss of 7,000 hectares of forest (15,200 acres)—an area larger than Bermuda—between 2003 and 2009.

First strike against illegal gold mining in Peru: military destroys miners’ boats

(02/21/2011) Around a thousand Peruvian soldiers and police officers destroyed seven and seized thirteen boats used by illegal gold miners in the Peruvian Amazon, reports the AFP. The move is seen as a first strike against the environmentally destructive mining. Used to pump silt up from the river-bed, the boats are essential tools of the illegal gold mining trade which is booming in parts of the Amazon.

Peru’s rainforest highway triggers surge in deforestation, according to new 3D forest mapping

(09/06/2010) Scientists using a combination of satellite imagery, airborne-laser technology, and ground-based plot surveys to create three-dimensional high resolution carbon maps of the Amazon rainforest have documented a surge in emissions from deforestation and selective logging following the paving of the Trans-Oceanic Highway in Peru. The study, published this week in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals that selective logging and other forms of forest degradation in Peru account for nearly a third of emissions compared to deforestation alone.

High mineral prices drive rainforest destruction

(08/13/2008) The surging price of minerals is contributing to degradation and destruction of rainforests worldwide, warns a researcher writing in the current issue of New Scientist.