One of EDGE’s focal mammals: the red slender loris (Loris tardigradus). Photo by: James T. Reardon/ZSL.

What do Attenborough’s echidna, the bumblebee bat, and the purple frog have in common? They have all received conservation attention from a unique program by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) called EDGE. Five years old this week, the program focuses on the world’s most unique and imperiled animal species or, as they put it, the most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species. In the past five years the program has achieved notable successes from confirming the existence of long unseen species (Attenborough’s echidna) to taking the first photos and video of a number of targeted animals (the purple frog).

“Since we started our work we’ve achieved measurable conservation gains for more than 20 species but still have a long way to go to reach our goal of securing the future for all top 100 EDGE species,” Carly Waterman, EDGE Program Manager, said in a press release.

Likely new species of elephant shrew, or sengi, in Kenya. Photo by: ZSL. |

A first in conservation, the EDGE program chooses its target species not based on fame and beauty (factors that bring in donors), but on a scientifically determined EDGE “score”. This carefully calculated score informs scientists both how threatened a species is and how unique it is on the tree of life. In other words, a species with a lot of close relatives—say a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus)—would have a lower EDGE score than one that stood alone—the duckbill platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)—just as a species that was classified as Critically Endangered would have a higher score than one deemed generally safe. Targeting animals with high EDGE scores means the program has largely focused on species that have been long neglected by big conservation NGOs.

“When we launched the list of the top 100 EDGE mammals, we realized that over two thirds of those on the list were receiving little or no conservation attention. The situation is even bleaker for the EDGE amphibian and coral species,” says Waterman.

The program started with mammals in January 2007, listing the world’s top 100 EDGE mammals and choosing ten to focus on initially. The next year the program kicked-off EDGE amphibians, and EDGE Coral Reefs was launched in 2011. Bird and shark lists are expected in the new few years, after those “fish, reptiles, and various plant groups in the near future,” according to the website.

Successes

The EDGE program has had an eventful five years. It has re-discovered three lost species, took the first photos of five species, and was instrumental in the discovery of a new mammal.

In 2007 the group found evidence of the survival of Attenborough’s echidna (Zaglossus attenboroughi), which many researchers had feared was extinct; also that year EDGE captured the first ever footage of the long-eared jerboa (Euchoreutes naso), a rodent from the deserts of Mongolia that quickly endeared itself to the global public. In 2008 camera traps took the first photo of the pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis) in Liberia during an EDGE expedition. In 2009 the purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis), which spends most of its life underground, was caught on video camera by EDGE for the first time, chirping happily away; also in 2009 EDGE confirmed the existence of the Hispaniola solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) in Haiti, a weird, endangered venomous mammal with teeth that sport poison; and the group rediscovered the Horton plains slender loris (Loris tardigradus nyctoceboides) in Sri Lanka after it had not been recorded for 65 years. In 2010 an EDGE fellow startled the world with the likely discovery of a new species of elephant shrew in a dwindling forest in Kenya, where she was busy studying a different elephant shrew. Last year an EDGE fellow recorded the first record of Bullock’s false toad (Telmatobufo bullocki) in six years.

The first ever photos of pygmy hippo in Liberia. Photo by: ZSL. |

In addition to these and other discoveries, EDGE has trained 26 fellows from 17 countries around the world. It has also conducted research that led to some species happily being taken off the EDGE, for example by discovering larger populations than expected, such as with the bumblebee bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai) and the long-eared jerboa.

Currently the EDGE is focused on 33 amphibians, 11 mammals, and 10 coral species. This year, EDGE has an expedition to Isla de Escuda off the Panamanian coast to assess the state of the world’s rarest, and smallest, sloth: the aptly named pygmy sloth (Bradypus pygmaeus). Surviving on the single island, the sloth is thought to be down to just a few hundred individuals.

Extinction

Of course, working with some of the world’s most neglected, and endangered, species is not all happy discoveries. When the program premiered in 2007 the number one EDGE species was the baiji, or the Yangtze river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer). A few months later and the baiji was declared “functionally extinct” after an intensive survey failed to find a single animal. Very likely the baiji is gone for good, killed off by numerous and large environmental impacts on China’s Yangtze River over the past few decades.

“It may be too late for the baiji, but with the help of their global community of supporters, the EDGE team is determined that the world’s most extraordinary species receive the attention they deserve,” Waterman says. “Once these unique species are lost, a whole branch of the world’s evolutionary tree is gone forever. We must not let that happen.”

_S-D-Biju.568.jpg)

The truly bizarre purple frog. Photo by: S.D. Biju.

EDGE’s next expedition will be to assess the pygmy sloth. Photo by: Bryson Voirin.

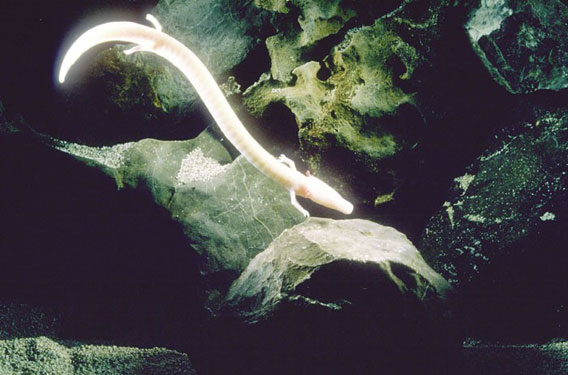

The olm (Proteus anguinus), a blind cave-dwelling amphibian, is a focal species of the EDGE program. Photo by: Arne Hodali.

The baiji, once the world’s number one EDGE mammal, likely went extinct a few months after the organization kicked-off. Photo by: Wang Ding.

Related articles

Updating the top 100 weirdest and most imperiled mammals

(01/24/2011) A lot can change in three years. In January 2007, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) jumpstarted a program unique in the conservation world: EDGE, which stands for Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered, selects the species it works with not based on popularity or fund-raising potential but on how endangered and evolutionary unique (in laymen’s terms: weird) they are. When EDGE first arrived in 2007, it made news with its announcement of the world’s top 100 most unique and endangered mammals. While this list included a number of well-known species—such as the blue whale and the Asian elephant—it also introduced the public to many little-recognized mammals that share our planet, such as the adorable long-eared jerboa, the ancient poisonous solenodon, and the ET-like aye-aye. However, after three years the EDGE program found that their top 100 mammals list already need updating.

Photos: Scientists race to protect world’s most endangered corals

(01/11/2011) As corals around the world disappear at alarming rates, scientists are racing to protect the ones they can. At a workshop led by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), the world’s foremost coral experts met in response to a decade of unprecedented reef destruction to identify and develop conservation plans for the ten most critically endangered coral species.

Seeking out the world’s rarest and most endangered birds

(02/02/2009) For an evolutionary biologist there is no conservation group whose work is more exciting than EDGE, a program developed by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Unique in the conservation world, EDGE chooses the species to focus on based on a combination of their threat of extinction and evolutionary distinctness. Katrina Fellerman, an evolutionary biologist herself and the EDGE birds’ coordinator, describes the organization as one that focuses on species, which “to put it bluntly, if lost, there would be nothing like them left in the world today”. Explaining further Fellerman says “We use evolutionary distinctiveness (ED) as a species-specific measure of the relative evolutionary value of species – it is a way of apportioning conservation value according to a species’ phylogenetic position. Species with few or no close relatives on the ‘tree of life’ have the highest ED scores.”