Self-organizing networks and open-source ventures in the age of global disruption

“The American Empire, and the global political economy it has spawned, is unraveling—not because of some far-flung external danger, but under the weight of its own internal contradictions. It is unsustainable—already in overshoot of the earth’s natural systems, exhausting its own resource base, alienating the vast majority of the human and planetary population. The solution in Tunisia, in Egypt, in the entire Middle East, and beyond, does not lay merely in aspirations for democracy. Hope can only spring from a fundamental re-evaluation of the entire structure of our civilization in its current form. If we do not use the opportunities presented by these crises to push for fundamental structural change, then the ‘contagion’ will engulf us all.”

—Dr. Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed.

For decades, climate change scientists have called for urgent change in the “Business-as-Usual (BAU) paradigm” to cope with the interlinking social, economic, and environmental issues of the 21st Century. In 2001, one of the world’s largest earth science organizations, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program (IGBP), published “A Planet Under Pressure,” a summary report for policy makers. The report’s critical statement was largely ignored:

-

[W]e know that the Earth System has moved well outside the range of natural variability exhibited over the last half million years at least. The nature of changes now occurring simultaneously in the global environment, their magnitudes and rates, are unprecedented in human history, and probably in the history of the planet. The Earth is now operating in a no-analogue state. On the other hand, we do not yet know where critical thresholds may lie. (1)

The IGBP’s description of the consequences of BAU are clearer when the veil of jargon that typically ensnares global change summary reports for policy makers is removed. Their statements may be translated as: the current, dominant global economic system functions as a massive, growth-generating hierarchy to support extractive, unsustainable lifestyles of a relatively small number of beneficiaries while the majority of the human population, as well as wilderness and intact ecosystems, absorb the externalities.

In sum, the Earth system cannot support an exponentially increasing human population adhering to the normative standards of industrial civilization. Systemic alteration is inevitable, and the recent success of self-organizing, leaderless revolutions as well as open-source collaborative movements reveal powerful alternatives. These developing trends may evolve into the framework for complex societies that are immune to many of the inherent shortcomings of ‘Business-as-Usual’ practices, and can adapt rapidly to modern global change conditions.

Sprawl outside Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

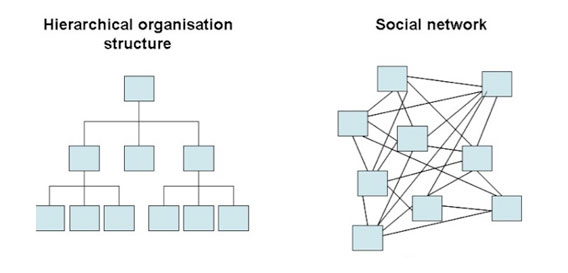

A pattern of crucial themes has begun to materialize in the search for viable economic solutions, environmental justice, and social welfare worldwide. The complex dynamics of social and environmental systems seem best conceptualized within the context of an overarching conflict between hierarchical organizations and the introduction of localized, do-it-yourself (DIY) adaptations to global change crises.

In regard to this systemic conflict between state and non-state entities, analyst and author Jeffery Vail explains, “Having spent the past nine years in the intelligence and counter-terrorism community, I am forced to conclude that our increasing failure to combat terrorism is not merely a failure of programs and policies but rather the fundamental failure of the Nation-State paradigm… globalization and multiculturalism are invalidating the Cartesian geography that is the foundation of the Nation-State laying the framework for the coming structural, epochal conflict of hierarchy vs. rhizome (2).”

Vail describes the ongoing systemic change in terms of hierarchy versus decentralized, self-organizing networks, or ‘rhizome’ power structures: “In order to resolve the deficiencies fundamental to the structure of hierarchy we must, by definition, abandon hierarchy as an organizing principle. We must confront hierarchy with its opposite: rhizome.”

Hence, the systemic changes that may deliver societies beyond industrial civilization cannot be expected to originate from within BAU organizations, though they may be capable of eventually altering these power structures. Kevin Carson of the Center for a Stateless Society says, “All proposals for ‘reform’ within the present system are designed to be implemented within existing structures, by the sorts of people currently running the dominant institutions. Anything that fundamentally weakened or altered the present pattern of corporate-state domination, or required eliminating the power of elites running the dominant institutions, would be—by definition—’too radical.'”

The severity and extent of contemporary global change conditions affect all facets of modern life, demanding solutions beyond the capacity of most dominant power structures. As droughts, famine, economic collapse, corruption, over harvesting, decimation of entire ecosystems, and violent conflicts erupt worldwide, traditional, hierarchical governments and most established BAU organizations are increasingly unable to provide legitimate solutions. The shift of influence from over-burdened, brittle governance to global communities of self-organizing yet autonomous collaborators presents the initial phases of the transition; as their success becomes evident, networks and non-hierarchical organizational strategies are likely to become increasingly adopted.

The ongoing, massive floods in Thailand are another of the recent climate-linked catastrophes effecting both regional as well as global markets. Environmentalists’ descriptions of apocalyptic disaster scenarios may no longer be dismissed as over-sensitive hyperbole. Recent floods, fires, droughts, and similar climatic disasters have led to systems disruption that ripples through the highly interconnected global economy (4). Photo by: US Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Robert J. Maurer.

The shortcomings of the “Business-as-usual” paradigm (and hierarchical power structures in general) share many similarities to the ongoing failure of global governance and NGOs to confront the feedback cycles of failed states and environmental catastrophes. Just as big banks, national governments, and global policy makers have been paralyzed in the face of widespread social, economic, food, and environmental crises, so also do mainstream environmental organizations and institutional science hesitate to confront catastrophic global change. The disturbing inability to address climate change from a systems perspective exemplifies this trend. Both policy planners as well as the majority of scientists remain locked in the habits and procedures of the hierarchy (3).

Hierarchical human social structures are organizations in which one agent or group exerts complete power over various levels of stratified, subordinate agents. In the hierarchy, group decision making is dictated by a sole entity, and communication is hampered by those lower on the hierarchy who maintain their positions by denying anything that may threaten the system’s structure. Communication, therefore, is often distorted as it flows up the chain of command or status, an unintentional side-effect of the cultural forces imposed to support the power structure and status of adherents. The IGBP’s year-after-year, unrequited clamoring that the ‘business-as-usual paradigm’ of coping with global change is not sustainable exemplifies the issue: the changes required to introduce appropriate non-BAU models are not only radically alien to governments and institutions, but also directly threaten their existence. Equitable, globalized protection of natural resources and autonomy for the sake of all of life have no part in national, market, or hierarchical/growth-dependent organizations’ interests.

Violence, information dissemination, and financial support within hierarchies tend to flow in unique and limited directions. Violence is acceptable so long as it flows down from higher to lower levels of stratification, such as widespread acceptance of the inherent violence required for the extraction and use of fossil fuels. Humankind survived and prospered without fossil fuels during periods with far fewer alternatives, intelligence, and communication abilities than present day. Industrial society cannot, however, survive without fossil fuels. The social norms and culture of fossil-fueled societies condition group members to accept the accompanying violence of fossil fuel extraction. This culture typically vilifies any threats against the system or those at the highest level of stratification, regardless of the violence done to those on the lower stratifications. Unconscious social patterning and assumptions reinforced by culture are predominantly responsible for our treatment of violence, as author, environmentalist, and activist Derrick Jensen notes:

Civilization is based on a clearly defined and widely accepted yet often unarticulated hierarchy. Violence done by those higher on the hierarchy to those lower is nearly always invisible, that is, unnoticed. When it is noticed, it is fully rationalized. Violence done by those lower on the hierarchy to those higher is unthinkable, and when it does occur is regarded with shock, horror, and the fetishization of the victims (5).

Castle Gate coal-fired power plant in Utah. Nearly half of the US’s electricity is from coal, the most carbon intensive energy. Photo by: David Jolley. |

Morality and group behavior evolved for the support of hierarchical social arrangements and ‘within group’ social adhesion. The delineations of ‘self’ and ‘other’ in previous, unconnected groups served the needs of the social organizational structure. The conflict between hierarchical and rhizome/networked societies is between those clinging to power, status, and exclusive, competitive behaviors and those who extend their self-image to include cooperating, like-minded groups and a stable Earth System (6).

Coordination and decision-making in rhizome/networked societies are opposite to those of typical hierarchical structures. Rhizomes are collaborative, collective, and determined by group consensus instead of by an arbitrarily positioned and dominant leader. The structure is alive and adaptive: ideas and guidance generally spring from that which benefits to the entire group, opposed to those highest in status (7).

Yochai Benkler describes the advantages of novel social and economic collaborations:

-

Computation, storage, and communications capacity are in the hands of practically every connected person. And these are the basic physical capital means necessary for producing information, knowledge, and culture—in the hands of something like 600 million to a billion people around the planet. What this means is that for the first time since the industrial revolution the most important means—the most important components—of the core economic activities… of the most advanced economies… are in the hands of the people at large. …Social production is a real fact, not a fad. It is the critical long-term shift caused by the internet. Social relations and exchange become significantly more important than they ever were as an economic phenomenon… it’s sustainable and growing fast, but… it is threatened by – in the same way it threatens – the incumbent industrial systems (8).

In the ongoing Wall Street and now global “Occupations” or permanent protests, an emergent, self-organizing social scheme presents a significant challenge to the hierarchy. While this may not fit the definition of a true human social superorganism (in the terms of Wilson and Holldobler in “The Superorganism” ), the “Occupy” movements display an extraordinary range of networked self-sufficiency and leaderless organization. The open sharing, widespread connections, and redundancies of the “Occupy” movements exemplify the abilities of network/rhizome structures to adapt and generate novel, unexpected techniques and tactics.

The “Human Microphone” phenomenon is case in point. Since New York City laws demand a permit to use “amplified sound,” and police have used bullhorns to attempt to interrupt speakers, protestors have adopted a tactic of repeating as a group the orations of single speakers. The coordination and power of this type of emergent human social engineering are simple, effective, and replicable. As its adaptive potential is displayed, the tactic spreads virally (10). The clear result demonstrated by the human-microphone effect exemplifies the success of social coordination over technology.

Additionally, “Occupy Wall Street” has developed a rapidly growing system of resources and provisions including food, shelter, medicine, exercise/meditation, media, computer access, and recreation. The viral spread of the movement has attracted celebrities including Mike Myers, Naomi Klein, Kayne West, Michael Moore, Susan Sarandon, Michael Franti, and Noam Chomsky.

Assistant professor of sociology at Fordham University, Dr. Heather Gautney, characterizes the systemic-level nature of leaderless, self-organizing movements:

-

Implicit in this structure is also a rejection of the narcissistic, ‘I know what’s good for you’ form of leadership, now pervasive in this country, in which lawmakers fail to consider the needs and desires of the people they claim to represent. The failure of representative democracy in the United States is perhaps one of the most serious problems of our time, and the Occupy movement is a symptom of this crisis of legitimacy. The people no longer trust their leaders and are even starting to indict the system itself. They think we can do better. We are all leaders.

Attending several of the Occupy movement’s General Assemblies (GA) provides a clear perspective of the profound shift in organizational tactics. While many mainstream media outlets criticize the movement’s “lack of a leader” and “unclear agenda,” a patient and objective observation of the GA meetings demonstrates the shift in tactics, communication, and awareness of the faults of traditional revolutions and revolutionary leaders.

In the face of impending, compounding global disasters, it seems surreal that the archaic habits of consistently failed leadership and hierarchies persist. Apparently our shared evolutionary inheritance of power and status struggle has profoundly imbedded itself in modern human culture (11).

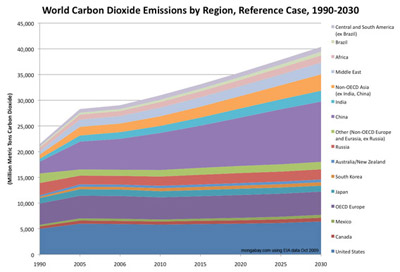

Carbon Dioxide Emissions by Country, 1990-2030. Click image to enlarge. |

Unfortunately, the greatest force uniting a human social organizational paradigm is the need to maintain its own structure regardless of the welfare of its adherents. Just as biologist and author Richard Dawkins exposed the “selfish” gene’s need to propagate regardless of the host organism’s long-term welfare, it seems that “selfish memes” have evolved through cultural selection in order to preserve social organizational models, often sacrificing individuals to preserve cultural traits (12). During the Battle of Saipan in WWII, more than 20,000 Japanese committed suicide to avoid capture by US forces, many jumping off the ‘Banzai Cliff’ or ‘Suicide Cliff’. If the impetus for personal survival and prosperity—true “selfishness” at the individual level—were more powerful than the urges of group selection, these instances of mass suicide would not occur(13). Vexed by Japanese civilians’ willingness to surrender instead of adopting the strict “fight to the death” code of Japanese culture, Emperor Hirohito ordered Japanese civilians at Saipan to commit suicide, promising the same posthumous status as that of soldiers who died in combat. One wonders how a culture adopts and clings to suicidal behaviors that certainly do not benefit the particular group. For the benefit of a stratified class system, however, programming a culture and its lower-status adherents to fight to the death is very beneficial.

Some anthropologists also suspect that Japan’s rugged geography and small size also contributed to the development of warfare in which retreat was difficult. Success in battle depended on a mentality of complete fearlessness and willingness to die. The famous Japanese text,” Hagakure,” reveals some of the memes used to compose a society primed for what may be termed “memetic apoptosis,” the programmed death of the agents composing the group. In many instances, hierarchical social groups will culturally program their pawns—their lower status ranks—with ideals and behaviors that lead to individual sacrifice for the benefit of the elite class as well as the organizational structure. The Samurai text proclaims:

-

“Even if it seems certain that you will lose, retaliate. Neither wisdom nor technique has a place in this. A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death. By doing this, you will awaken from your dreams,” and “Meditation on inevitable death should be performed daily. Every day, when one’s body and mind are at peace, one should meditate upon being ripped apart by arrows, rifles, spears, and swords, being carried away by surging waves, being thrown into the midst of a great fire, being struck by lightning, being shaken to death by a great earthquake, falling from thousand-foot cliffs, dying of disease or committing seppuku at the death of one’s master. And every day, without fail, one should consider himself as dead. This is the substance of the Way of the Samurai.”

Biologist and evolutionary theorist Richard Dawkins explains this conundrum: “A meme that made its bodies run over cliffs would have a fate like that of a gene for making bodies run over cliffs. It would tend to be eliminated from the meme-pool. … But this does not mean that the ultimate criterion for success in meme selection is gene survival. … Obviously, a meme that causes individuals bearing it to run off cliffs has a grave disadvantage, but not necessarily a fatal one. … a suicidal meme can spread, as when a dramatic and well-publicized martydom inspires others to die for a deeply loved cause, and this in turn inspires others to die, and so on.” Evolutionary theory applies to more than just DNA and genes; as Dawkins observes, “all of life evolves by the differential survival of replicating entities.”

A comparison of the hallmark characteristics of social organizational structures reveals the inefficiencies of the hierarchy—especially during times of duress.

The unconscious phenomenon of memetic influence over inherent biological urges (the will to survive as an individual) appears to be controlled predominantly by cultural traits that are reinforced daily in conversation, music, art, status games, economic interactions, and a variety of social cues and conditioning. Hierarchical cultures program the social group on a day-to-day basis to adopt certain behavioral patterns given certain conditions. As the openness of modern communications rapidly reveals the many fallacies and flaws of these cultures as well as the benefits of social networking and autonomy, the emergent, more adaptive scheme spreads. Revealing both the physiological structures and neurochemistry of the mind that may lead to various destructive behaviors, and exposing the memetic influences that hijack these components, may be a crucial step in permanently preventing hierarchies from sacrificing their lower stratifications to fight, kill, and die to maintain centralized power and the status system.

Humans, along with many other social primates, use policing and pomp to bolster the hierarchy, displaying a variety of social signals designed to balance and bolster the status quo. The social cues supporting hierarchy in human cultures are infinite in their bounds and absurdity: slogans like “united we stand,” contrived for the adherence of a nation, may at one moment bring a sense of identity to the masses, yet are promptly discarded in trivial devotion to rival sports teams. Both nationalism and passionate loyalty to sports teams are cultural codifying factors that may drive groups to unify and fight. From family, to tribe, to city-state, to nation-state, to globalized market-state, the biological and memetic basis for hierarchy has remained buried beneath the collective consciousness, allowing the power structure to persist as human social groups evolved. Cultures have evolved and changed, but lacking the pressure to abandon the hierarchy they have retained many of its unconscious habits. The emergence and success of globally networked self-organizing social groups presents an incredible and stark contrast.

The philosopher Simone de Beauvoir observed, “society cares for the individual in so far as he is profitable.” The dominant socioeconomic systems, unfortunately, force us to exist and compete within extractive, destructive markets and unlimited growth-based organizational hierarchies, so that even ‘good’ and ‘profitable’ participants in society are systematically compelled to lead lifestyles with net destructive effects on the Earth system. Even most environmental scientists and researchers are required to support (at some level) destructive industries, corrupt governments, militaries, and ineffective policy through taxation and participation in modern culture. From within our current system we are allowed to contribute mostly insignificant, arbitrary change. The system itself—its adherents, culture, and collective consciousness — unthinkingly rejects alternatives that may pose systemic change. These complex cultural phenomena are rooted in human social biology and group behavior, the evolutionary vestiges of our hierarchical primate societies (14).

Most modern human culture and social organizational structures may be characterized as hypertrophic outgrowths of the basic primate hierarchy. Through competition for power, status, and reproductive rights, evolution has reared most humans as imperial apes. Group decision-making and social adhesion are subjected to the forces of the hierarchy: just as many primate troops typically satisfy their own survival necessities at the whims of an alpha male, humans tend to assume the apes ‘in charge’ are best equipped to satisfy the interests of the group. Human culture remains somewhat entrenched in the habits of the primate hierarchy; we tend to revere and worship the familiar and established emblems, flags, celebrities, organizations, leaders, and institutions of the cultures in which we are raised.

Anthropologists Lionel Tiger and Robin Fox note the often frustrating conventions of power and place in human social groups: “No matter how hard and how often we rail against them, the affections for difference in status are also part of our primate structure… We refine this reflex endlessly; we humiliate others; we are rank-makers and flag planters. We create a god to whom we can subordinate. So committed are we to the notion of hierarchy… that even our mightiest leaders must subserve something or someone.” The notion of ‘gods’ is inextricably linked to power, dominance, and the social habits of civilization and hierarchies (15).

In “On the Genealogy of Morals”, Nietzsche also recognized this pattern of status and rank-placing within human culture and interactions, as well as its relation to the divine authority of gods: “As history teaches us, the consciousness of being in debt to the gods did not in any way come to an end after the downfall of the organization of the ‘community’ based on blood relationships. Just as humanity inherited the ideas of ‘good and bad’ from the nobility of the tribe (together with its fundamental psychological tendency to set up orders of rank), in the same way people also inherited, as well as the divinities of the tribe and of the extended family, the pressure of as yet unpaid debts and the desire to be relieved of them.”

Both tribal and primitive communities and modern culture likely inherited many other socio-organizational elements from the primate hierarchy. Aldous Huxley additionally links strict hierarchies with monotheistic gods: “Totalitarian regimes justify their existence by means of a philosophy of political monism, according to which the state is God on earth, unification under the heel of the divine state is salvation, and all means to such unification, however intrinsically wicked, are right and may be used without scruple. This political monism leads in practice to excessive privilege and power for the few and oppression for the many, to discontent at home and war abroad.”

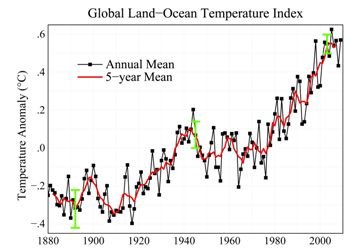

Covering global surface temperatures from 1880-2000, the graph shows global annual surface temperatures relative to 1951-1980 mean temperatures. Except for a leveling off between the 1940s and 1970s, Earth’s surface temperatures have increased since 1880. As shown by the red line, long-term trends are more apparent when temperatures are averaged over a five year period. Image credit: NASA/GISS. |

While hierarchy is not necessarily the sole organizational paradigm of human social structures, it seems to be the default given ample resources and stable conditions. Hierarchy, however, requires centralization of power and dependence, commonly resulting in break-down and revolution when social and environmental circumstances become intolerable for a significant portion of a society. In his critical dissection, “On Human Nature”, E. O. Wilson explains this phenomenon:

Large-scale slavery begins when the traditional mode of production is dislocated, usually due to warfare, imperial expansion, and changes in basic crops, which in turn induces the rural free poor to migrate into cities and newly opened colonial settlements. At the imperial center land and capital fall increasingly under the monopoly of the rich, while citizen labor grows scarcer. The territorial expansion of the state, by making the enslavement of other peoples profitable, temporarily solves the economic problem. Were human beings then molded by the new culture, were they able to behave like the red Polyergus ants for which slavery is an automatic response, slave societies might become permanent. But the qualities that we recognize as most distinctively mammalian—and human—make such a transition impossible.

When formalized slavery as a human social institution is analyzed historically, we find that it repeats a very similar cycle, always resulting in failure. Apparently, aspects of human ontogeny support neither slavery nor hierarchical civilization (which depends on some form of slavery).

Autonomous, non-growth-generating social structures devoted to creating net restorative external effects may be one of the most substantial leaps in the development of human organization since the transition from hunter-gatherer groups into sedentary populations. Emerging networks and open-source movements may be among the most progressive leaps in this direction.

The description ‘open source’ (OS) is borrowed from programming terminology, where it refers to a movement favoring cooperation and the free sharing of programming source code or information in general. The power behind the movement is based in the collective acknowledgment within the OS community that the combined efforts of many individuals sharing and working in unison may contribute to much more than the sum of the parts. While we have been conditioned to recognize power in terms of monetary affluence and military might, 21st century trends indicate a momentous shift in power from organizational hierarchies to social networks. Several decades ago many prominent thinkers foresaw such alterations through the study of systemic trends in the natural world. In “Conscious Evolution,” author and futurist Barbara Marx Hubbard explains the power of networked interactions: “[S]ystems become more complex by non-linear, exponentially increasing numbers of interactions of incremental innovations. At some point apparently insignificant innovations connect in a non-linear manner.”

World culture has already been significantly jolted by the viral success of open-source movements, information campaigns, and tools. The success of the information tool Wikipedia, the spread of “open-source insurgencies” in the Middle East, North Africa, and now globally, the popularity and support for Wikileaks, the advent of the decentralized, peer-to-peer currency “Bitcoin,” hackerspaces/makerspaces, the progress of Open-Source Ecology, and the recent global spread of the “Occupy” movement, indicate the potential of novel collaborative efforts in a diverse range of fields.

Historical characterizations of human societies often fail to grasp the longer-term evolutionary patterns underlying the transitions between archaic, primal power hierarchies and emergent social trends. Placing human social behavior, cultural evolution, history and the persistent phenomenon of revolution within the larger context of cultural and conscious evolution may produce a more complete image.

Humans most certainly have undergone periods of wild and rapid cultural evolution; the difficulty of interpreting the writing, culture, and mindset of early civilizations leaves an abyss in human consciousness studies and paleopsychology that demands exploration. It is doubtful that hunter-gatherer groups at the dawn of civilization were fully or even partially able to describe the details of the transition to sedentary civilizations. Similarly, we are presently stumbling to articulate what may become the next great leap in complex socialization of global humanity. The urgency for revolution is evident, as is recognition that no one leader, revolutionary, nation, institution, culture, or class will be competent to stabilize 21st century global change.

See endnotes and further information: Civilization Shifting: Endnotes

Related articles

11 challenges facing 7 billion super-consumers

(10/31/2011) Perhaps the most disconcerting thing about Halloween this year is not the ghouls and goblins taking to the streets, but a baby born somewhere in the world. It’s not the baby’s or the parent’s fault, of course, but this child will become a part of an artificial, but still important, milestone: according to the UN, the Earth’s seventh billionth person will be born today. That’s seven billion people who require, in the very least, freshwater, food, shelter, medicine, and education. In some parts of the world, they will also have a car, an iPod, a suburban house and yard, pets, computers, a lawn-mower, a microwave, and perhaps a swimming pool. Though rarely addressed directly in policy (and more often than not avoided in polite conversations), the issue of overpopulation is central to environmentally sustainability and human welfare.

Sober up: world running out of time to keep planet from over-heating

(10/24/2011) If governments are to keep the pledge they made in Copenhagen to limit global warming within the ‘safe range’ of two degrees Celsius, they are running out of time, according to two sobering papers from Nature. One of the studies finds that if the world is to have a 66 percent chance of staying below a rise of two degrees Celsius, greenhouse gas emissions would need to peak in less than a decade and fall quickly thereafter. The other study predicts that pats of Europe, Asia, North Africa and Canada could see a rise beyond two degrees Celsius within just twenty years.

Adaptation, justice and morality in a warming world

(07/28/2011) If last year was the first in which climate change impacts became apparent worldwide—unprecedented drought and fires in Russia, megaflood in Pakistan, record drought in the Amazon, deadly floods in South America, plus record highs all over the place—this may be the year in which the American public sees climate change as no longer distant and abstract, but happening at home. With burning across the southwest, record drought in Texas, majors flooding in the Midwest, heatwaves everywhere, its becoming harder and harder to ignore the obvious. Climate change consultant and blogger, Brian Thomas, says these patterns are pushing ‘prominent scientists’ to state ‘more explicitly that the pattern we’re seeing today shows a definite climate change link,’ but that it may not yet change the public perception in the US.