Over the weekend more than 100 Shuar indigenous people, also known as Wampis, blockaded the Morona River in Peru in an effort to stop exploratory oil drilling by Canadian-owned Talisman Energy. The blockade in meant to prevent oil drilling in an area of the Peruvian Amazon known as Block 64, home to four indigenous tribes in total and the Pastaza River Wetland Complex, a Ramsar wetland site.

“We do not consider the oil company as a creator of jobs but instead as murderous, criminal and abusive. We do not want Talisman in the Wampis territory,” a statement from the Shuar reads pointing to Talisman Energy’s track record in Peru as well as alleged human rights abuses in Sudan during the nation’s civil war. The company sold off its Sudan holdings in 2003 after international criticism, while a lawsuit in the US against Talisman was thrown out due to sufficient admissible evidence. The US Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

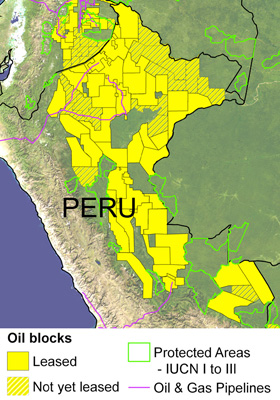

Oil and gas blocks in the western Amazon. Solid yellow indicates blocks already leased out to companies. Hashed yellow indicates proposed blocks or blocks still in the negotiation phase. Protected areas shown are those considered strictly protected by the IUCN (categories I to III). Image modified from Finer M, Jenkins CN, Pimm SL, Keane B, Ross C, 2008 Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002932 |

The Shuar blockade comes at a time when the new Peruvian administration is working to repair battered relations with indigenous groups. Earlier this month, Peru’s new president Ollanta Humala signed into law a measure requiring that industry consult indigenous groups prior to any activities on their land, including oil drilling. Although the law does not go so far as to give indigenous groups a ‘veto’ over industrial activities on their land.

“What we want to do with this law is have the voice of indigenous people be heard, and have them treated like citizens, not little children who are not consulted about anything,” Humala said at the signing.

The Shuar indigenous people contend that Talisman Energy had “not completed the prior process of consultation” before drilling on their land. Talisman drilling in Block 64 began in 2004.

Despite this, the CEO of Talisman, John Manzoni, has said the company will “only operate in areas where it has consent and support from local communities.”

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) the Pastaza River Wetland Complex—also located in Block 64—is the world’s largest Ramsar wetland site in the Amazon, exceeding 3.8 million hectares. Local people depend on the area for fishing and water.

“Talisman must respect the decision of the indigenous people living in and around Block 64 and halt oil exploration,” said Gregor MacLennan, Peru Program Coordinator with indigenous rights NGO Amazon Watch, in a press release. “The Shuar, together with the Achuar and other indigenous groups, are sending a clear message that they do not want to risk contaminating important watersheds and their ancestral hunting and fishing grounds by allowing oil development to go ahead.

Around 70 percent of the Peruvian Amazon has been opened for oil and gas exploration and drilling under an aggressive industrialization of the Amazon by previous Peruvian president Alan Garcia. The opening up of so much of the Amazon to exploitative activities has led to numerous conflicts between large companies and indigenous people. The situation came to a head in 2009. A standoff between indigenous protestors and government police ended with 23 police officers and at least 10 protesters dead, though indigenous people say that bodies of protesters were dumped in rivers to hide the numbers killed.

Related articles

Peru president signs indigenous rights act into law

(09/07/2011) Peru’s new president, Ollanta Humala, has signed into law a measure requiring that indigenous groups are consulted prior to any mining, logging, or oil and gas projects on their land. If properly enforced, the new legislation will give indigenous people free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) over such industrial projects, though the new law does not go so far as to allow local communities a veto over projects. Still, the law puts Peru in line with the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of 1989, which the South American nation ratified nearly two decades ago.

Oil company hires indigenous people to clean up its Amazon spill with rags and buckets

(07/13/2011) On Sunday morning children swimming in the Mashiria River in the Peruvian Amazon noticed oil floating on the water. A pipeline owned by Maple Energy had ruptured in Block 31-E, polluting the Mashiria River which is used by the Shipibo indigenous community in Nuevo Sucre for fishing and drinking water. In response to the spill, Maple Energy’s local operator—Dublin incorporate transnational—hired 32 Shipibo community members to clean up the spills using only rags and buckets.

ConocoPhillips withdraws from oil exploitation in uncontacted indigenous territory

(05/11/2011) ConocoPhillips has announced it is withdrawing from its 45% share of oil drilling in Block 39 of Peru’s Amazon rainforest. The withdrawal comes after pressure from indigenous-rights and environmental groups to leave two Peruvian oil blocks—39 and 67—alone, due to the presence of indigenous people who have chosen to remain uncontacted. ConocoPhillips and other companies have been warned they will ‘decimate’ tribes if they remain. However, Spanish oil company Repsol-YPF still operates in block 39 and is currently doing seismic testing for oil reserves in the untouched region. ConocoPhillips has not divulged what company is taking their place.