Lizards have evolved a variety of methods to escape predators: some will drop their tail if caught, many have coloring and patterning that blends in with their environment, a few have the ability to change their colors as their background changes, while a lot of them depend on bursts of speed to skitter away, but how does a lizard escape climate change? According to a new study in Science they don’t.

The study finds that lizards are suffering local extinctions worldwide due exclusively to warmer temperatures. The researchers conclude that climate change could push 20 percent of the world’s lizards to extinction within 70 years. Some places like Madagascar—with 210 species of lizards and half of the world’s chameleons—appear particularly susceptible to a mass extinction of lizards.

The story begins Mexico in the 1970s when study co-author Jack Sites, a biology professor at Brigham Young University, began surveying populations of Sceloporus (i.e. spiny) lizards.

“I had provided a baseline data set with precise localities where the lizards were common,” Sites explained. “But Mexican ecologists were going back every few years, and pretty soon the lizards were hard to find, and then they weren’t seeing any. These are protected areas, so the habitat’s still there. So you start to think there is something else going on.”

Madagascar is a hotspot of predicted extinction for lizards and members of the Chamaeleonidae family like this Furcifer lateralis are currently going extinct. Photo by: Ignacio De la Riva. |

Intrigued by the data professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Barry Sinervo, went to Mexico and surveyed 48 species of the spiny lizards in 200 sites in Mexico. Disturbingly, Sinervo found that 12 percent of the local populations had disappeared entirely.

But was this warmer temperatures or something regional that the team hadn’t noticed? The researchers then turned to other research projects in South America, Africa, Australia, and Europe. On all five continents the story was similar: lizard populations were dropping even in protected area.

“To get this kind of pattern, on five continents in 34 different groups of lizards, that’s not random, that’s a correlated response to something big,” Sites says. The researchers were especially careful to ensure that other factors, especially habitat degradation, weren’t causing the decline.

“We did a lot of work on the ground to validate the model and show that the extinctions are the result of climate change,” Sinervo said. “None of these are due to habitat loss. These sites are not disturbed in any way, and most of them are in national parks or other protected areas.”

The researchers believe that temperatures are simply rising too fast for lizards to adapt. For one thing on hot days, lizards must spend their day cooling off in the shade and so are unable, due to their cold-bloodedness, to seek out food.

“There are periods of the day when lizards can’t be out, and essentially have to retreat to cooler places,” Sinervo explains. “When they’re not out and about, lizards aren’t foraging for food.”

Many species have yet to be discovered and named across the world, as exemplified by this unnamed Liolaemus species from Bolivia. Many of these species could disappear before they are formally described. Photo by: Ignacio De la Riva. |

In addition, if temperatures are particularly hot during the reproductive cycle, lizard mothers aren’t able to get their energy-requirements to support eggs or embryos.

“The heat doesn’t kill them, they just don’t reproduce,” Sites said. “It doesn’t take too much of that and the population starts to crash.”

In fact, lizards that bear live young rather than eggs appear to be more negatively affected by climate change.

“Live-bearers experience almost twice the risk of egg-layers largely because live-bearers have evolved lower body temperatures that heighten extinction risk,” Sinervo said. “We are literally watching these species disappear before our eyes.”

The researchers also found evidence of lizard migrations due to a changing climate, a phenomenon that has been shown in a wide-variety of species from birds to mammals to trees.

“We are actually seeing lowland [lizard] species moving upward in elevation, slowly driving upland species extinct, and if the upland species can’t evolve fast enough then they’re going to continue to go extinct,” Sinervo explains.

Researchers say that the prediction of a 20 percent extinction rate could decline if humans effectively slow anthropogenic climate change. However they expect lizard populations to decline significantly over the next few decades regardless: in fact they estimate that approximately 6 percent of lizard species will vanish by 2050 whether emissions are lowered or not, since carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for decades.

Lizards play important ecological roles in the world’s environments since they are a vital prey source for a variety of species, including birds and snakes. Dropping lizard populations is likely to hit lizard-eaters hard. In addition, lizards prey heavily on insects.

“We could see other species collapse on the upper end of the food chain, and a release on insect populations,” Sinervo says.

For researchers who have spent their life studying lizards, the news that the small reptiles are far acutely susceptible to warming temperatures—and already disappearing—is disheartening to say the least.

“It’s a terrible sinking feeling,” Sites says of the study’s dire conclusions. “When I first saw the data, I thought, ‘Can this really be happening?'”

“If the governments of the world can implement a concerted change to limit our carbon dioxide emissions, then we could bend the curve and hold levels of extinction to the 2050 scenarios,” Sinervo concludes. “But it has to be a global push… I don’t want to tell my child that we once had a chance to save these lizards, but we didn’t. I want to do my best to save them while I can.”

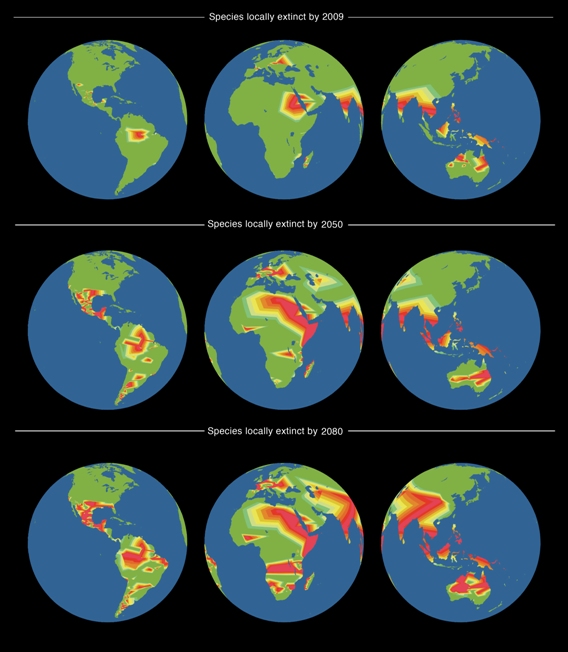

Global maps of observed local extinctions in 2009, and projections for 2050 and 2080 based on geographic distributions of lizard families of the world. Map by: Barry Sinervo.

Related articles

Climate change could devastate lizards in the tropics

(03/04/2009) With help from data collected thirty years ago, scientists have discovered that tropical lizards may be particularly sensitive to a warming world. Researchers found that lizards in the tropics are more sensitive to higher temperatures than their relatives in cooler, yet more variable climates. “The least heat-tolerant lizards in the world are found at the lowest latitudes, in the tropical forests. I find that amazing,” said Raymond Huey, lead author of a paper appearing in the March 4 Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Reptiles underrepresented on the IUCN Red List

(11/04/2009) Currently there are an estimated nearly 9,000 reptiles in the world, while the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List has assessed all of the world’s described mammals, birds, and amphibians, reptiles have yet to be fully assessed, leaving herpetologists with an unclear picture of how reptiles are faring in the world. Currently, 1,677 reptiles have been assessed (less than 20 percent of the total number of reptile species known) with 293 added this year.

World’s only blue lizard heads toward extinction

(03/07/2007) High above the forest floor on the remote Colombian island of Gorgona lives a lizard with brilliant blue skin, rivaling the color of the sky. Anolis gorgonae, or the blue anole, is a species so elusive and rare, that scientists have been unable to give even an estimate of its population. Due to the lizard&spod;s isolated habitat and reclusive habits, researchers know little about the blue anole, but are captivated by its stunning coloration.