According to a new study published in Science the Arctic should be cooling, and in fact has been cooling for millennia. But beginning in 1900 Arctic summer temperatures began rising until the mid-1990s when the cooling trend was completely overcome. Researchers fear that this sudden up-tick in temperatures could lead to rising sea levels threatening coastal cities and islands.

“Scientists have known for a while that the current period of warming was preceded by a long-term cooling trend,” said lead author Darrell Kaufman of Northern Arizona University. “But our reconstruction quantifies the cooling with greater certainty than ever before.”

Researchers secure a floating platform used to take sediment cores from Sunday Lake in southwestern Alaska. Sediment generated by the small cirque glacier is carried to the lake by meltwater. The amount of sediment delivered to the lake can vary with the intensity of the summer melt season. Photo by: Darrell Kaufman, Northern Arizona University. |

Why a ‘wobble’ matters

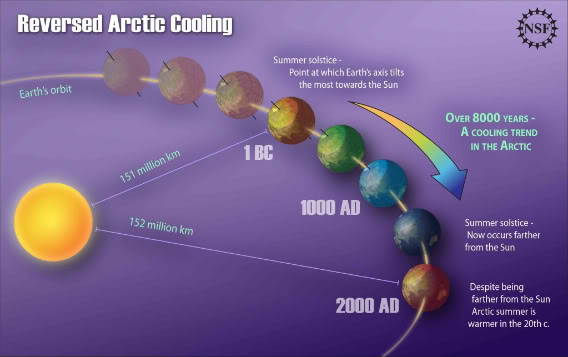

For the past 8,000 years the distance between the Earth and the sun has been increasing due to a wobble in the Earth’s tilt toward the sun. This distance has decreased summer sunshine in the Arctic, thereby causing the long-term cooling trend, which should have continued for another 4,000 years before reversing. However, in the 20th century greenhouse gas emissions have overwhelmed that natural cycle: the decade from 1998 to 2008 was the warmest in the last two thousand years reconstructed by the scientists.

“The amount of energy we’re getting from the sun in the 20th century continued to go down, but the temperature went up higher than anything we’ve seen in the last 2,000 years,” said team member Nicholas P. McKay of The University of Arizona in Tucson, a doctoral candidate in geosciences. “The 20th century is the first century for which how much energy we’re getting from the sun is no longer the most important thing governing the temperature of the Arctic.”

The space between the sun and the Earth continues to grow, however, due to greenhouse gas emissions “we expect the Arctic will continue to warm in the coming decades, increasing land-based ice loss and triggering global increases in sea-level rise,” added Professor Gifford Miller of Colorado University-Boulder’s Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research.

Currently Arctic temperatures average about 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit higher than they would be if the cooling trend had been allowed to continue, explained Kaufman.

Not only will this likely affect sea levels, but precipitation patterns far from the Arctic.

“Winter storms in the western U.S. are going further north than they used to — and these are the same storms that bring our rain and snowfall,” McKay said.

The Arctic warms faster than the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, due to a process whereby decreasing sea and land ice has lead to increased absorption by the sun’s heat on exposed areas of the ocean and on snow-free land areas, which are darker and so absorb more heat. The process is known as ‘Arctic amplification’.

Hallet Lake, near the crest of the Chugach Mountain Range in south-central Alaska. Productivity in the lake is sensitive to summer temperature in the region. Researchers used sediment cores from Hallet Lake and others to construct a 2,000-year climate record for the Arctic. Photo by: Copyright 2006 Nicholas P. McKay. |

“With less sea ice in winter, the ocean returns the heat stored in summer to the atmosphere, resulting in warmer winters throughout the Arctic,” said Miller. “Because we know that the processes responsible for past Arctic amplification are still operating, we can anticipate that it will continue into the next century. The magnitude of change was surprising, and reinforces the conclusion that humans are significantly altering Earth’s climate.”

Reconstructing the Arctic’s past

Data from ancient lake sediments, ice cores, and tree rings allowed the researchers to reconstruct past Arctic temperature for the past 2,000 years on a decade-by-decade basis.

The team sampled two dozen Arctic lakes whose sediments are laid down in distinct annual layers. From these layers scientists can gleam important information related to temperature and climate: changes in the silica remnants left by algae in the layers correspond to the length of the growing season, while thicker annual layers corresponds to warmer summers, since more sediments are deposited due to increased glacier meltwater.

The research team set their findings from the sediment layers next to previously published findings from glacial ice cores and tree rings. They found that cooling occurred at an average rate of 0.36 degrees Fahrenheit (0.2 Celsius) every thousand years, but the trend reversed in the last century.

The team took then their findings from the field and compared it with simulations by the Community Climate System Model, a sophisticated computer model of global climate at National Center for Atmospheric Research(NCAR).

The computer modeling agreed with the researcher’s findings, which gives them greater faith in the ability of computer modeling to accurately predict future Arctic temperatures.

“This study provides us with a long-term record that reveals how greenhouse gases from human activities are overwhelming the Arctic’s natural climate system,” NCAR scientist and co-author David Schneider said. “This result is particularly important because the Arctic, perhaps more than any other region on Earth, is facing dramatic impacts from climate change.”

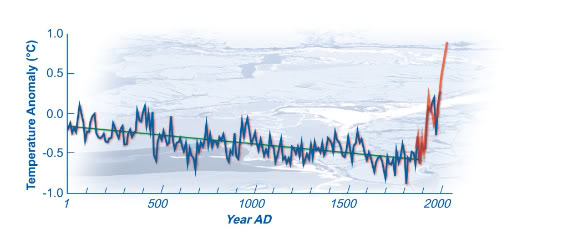

New research shows that the Arctic reversed a long-term cooling trend and began warming rapidly in recent decades. The blue line shows estimates of Arctic temperatures over the last 2,000 years, based on proxy records from lake sediments, ice cores and tree rings. The green line shows the long-term cooling trend. The red line shows the recent warming based on actual observations. A 2000-year transient climate simulation with NCAR’s Community Climate System Model shows the same overall temperature decrease as does the proxy temperature reconstruction, which gives scientists confidence that their estimates are accurate. Credit: Courtesy Science, modified by UCAR.

An illustration showing an abrupt reversal in Arctic cooling despite an increasing distance between the sun and Earth during the Arctic summer solstice. Credit: National Science Foundation.

Related articles

Summer sea ice likely to disappear in the Arctic by 2015

(08/31/2009) If current melting trends continue, the Arctic Ocean is likely to be free of summer sea ice by 2015, according to research presented at a conference organized by the National Space Institute at Technical University of Denmark, the Danish Meteorological Institute and the Greenland Climate Center.

NASA reveals dramatic thinning of Arctic sea ice

(07/07/2009) Arctic sea ice thinned dramatically between the winters of 2004 and 2008, with thin seasonal ice replacing thick older ice as the dominant type of sea ice for the first time on record, report NASA researchers. Scientists from NASA and the University of Washington used observations from NASA’s Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) to make the first Arctic Ocean basin-wide estimate of the thickness and volume of sea ice cover. The researchers found that overall Arctic sea ice thinned about 17.8 centimeters (7 inches) a year, for a total of 67 cm (2.2 feet) over the four winters from 2004 to 2008. The total area covered by thick older ice that survives one or more summers (“multi-year ice”) shrank 42 percent or 1.54 million square kilometers (595,000 square miles), leaving thinner first-year ice (“seasonal ice”) as the dominant type of ice in the region.

Arctic ecosystem in danger as ice thins

(04/07/2009) Recent dramatic news points to both poles undergoing transformation due to climate change. This weekend an ice bridge disintegrated on the Wilkins Ice Shelf in Antarctica, leaving the whole shelf vulnerable to melting, and then yesterday new evidence was released of the impact of warming in the Arctic. Younger thinner ice has become the dominant type in the Arctic over the past five years, reports a new study led by Research Associate Charles Fowler of the Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research. The thinner ice does not bode well for the Arctic ecosystem, as the ice is more prone to summer melting.

Black carbon linked to half of Arctic warming

(04/05/2009) Black carbon is responsible for 50 percent of the total temperature increases in the Arctic from 1890 to 2007 according to a study published in Nature Geoscience. Since 1890 the temperature in the Arctic has risen 1.9 degrees Celsius, linking black carbon to nearly an entire degree rise in Celsius or almost two degrees Fahrenheit.