A new report from published by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) highlights the benefits — and controversies — of large-scale expansion of oil palm agriculture in Southeast Asia.

The review, titled “The impacts and opportunities of oil palm in Southeast Asia: What do we know and what do we need to know?”, notes that while oil palm is a highly productive and profitable crop, there are serious concerns about its environmental and social impact when established on disputed land or in place of tropical forests and peatlands.

“Implementing oil palm developments involves many tradeoffs,” write the authors. “Oil palm’s considerable profitability offers wealth and development where wealth and development are needed—but also threatens traditional livelihoods. It offers a route out of poverty, while also making people vulnerable to exploitation, misinformation and market instabilities. It threatens rich biological diversity—while also offering the finance needed to protect forest. It offers a renewable source of fuel, but also threatens to increase global carbon emissions.”

Oil palm seed. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

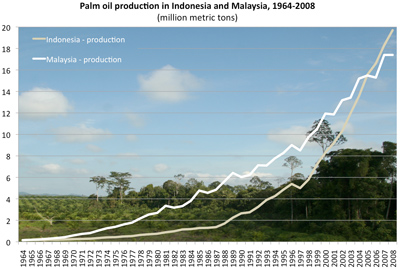

The report notes that the area allocated for oil palm has expanded dramatically since the early 1980s, more than tripling to 14 million hectares in 2007. With around 6.2 million hectares officially designated for oil palm, Indonesia is the world’s leading grower and producer, followed by Malaysia. This growth has created new fortunes in both countries, but has come at a high ecological cost: more than half of oil palm expansion in Malaysia and Indonesia between 1990 and 2005 occurred at the expense of natural forests. Expansion has further been linked to water and air pollution as well as substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Growth has also driven a shift in regional fire regimes. Today wild fires regularly char vast tracts of land across Sumatra and Borneo, two major frontiers for oil palm agriculture.

But if not oil palm, then what?

Although oil palm expansion has been linked to environmental problems, its high yield means palm oil can help meet future demand for vegetable oil at a lower land cost than other crops, including soy, rapeseed/canola, and sunflowers. But as the CIFOR report notes, much of the clearing done ostensibly for oil palm establishment isn’t actually planted with oil palm.

|

“The area cleared of forest in the name of oil palm establishment is believed to be several times the area actually planted, particularly in Indonesia,” write the authors. “This reflects the impacts of associated labor migrations and of plantation failure. It also reflects a form of timber theft in which investors clear-fell the forest in the guise of a plantation development and profit from the timber sales but abandon the project without developing plantations.”

Such details, which reflect the complexities of oil palm agriculture, have made the report itself controversial. It was held up for months due to political concerns. Nevertheless the report is now available online at www.cifor.cgiar.org/Publications/Detail?pid=2792.

The report is authored by Douglas Sheil of CIFOR; Anne Casson of Sekala; Erik Meijaard of The Nature Conservancy; Meine van Noordwijk of the World Agroforestry Centre; Joanne Gaskell of Stanford University; Jacqui Sunderland-Groves of CIFOR; Karah Wertz of CIFOR; and Markku Kanninen of CIFOR.

Sheil, D., Casson, A., Meijaard, E., van Nordwijk, M. Gaskell, J., Sunderland-Groves, J., Wertz, K. and Kanninen, M. 2009. The impacts and opportunities of oil palm in Southeast Asia: What do we know and what do we need to know? Occasional paper no. 51. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia.