This is the first in a series of tropical forest policy commentaries John-O Niles will be writing for Mongabay.com leading up to the December U.N. climate meeting in Copenhagen. John-O is the Director of the Tropical Forest Group.

In late 1991, I had just finished my undergraduate degree in forest economics at the University of Vermont. The Rio Earth Summit was approaching and everyone seemed to be wearing “Save the Rainforest” T-shirts. So, being 22 years old and green in more ways than one, I decided to hitchhike across Africa and see the rainforest myself. After a summer working in an Alaska salmon cannery to save some money and thumbing my way back across America in station wagons and 18 wheelers, I grabbed a $199 one-way flight to Spain. I crossed the Strait of Gibraltar on a ferry and proceeded to get solidly conned my first night in Morocco by one of Tangiers’ world-famous touts. I then got sick in the Sahara and stranded during a coup in Algeria. I stayed with a one-eyed farmer (Jo-Man) in Niger, and floated down the Niger River into northwestern Nigeria on a pirogue. I wandered around the notoriously difficult nation for a few weeks and then headed southeast to make my way into Cameroon. In Cameroon, I knew, I could see some real rainforests. While phoning home from Calabar, Nigeria, to my distraught mother (I hadn’t contacted her in months and she had called the State Department to report me missing), I ran into Liza Gadsby. Liza and her partner, Peter Jenkins, run Pandrillus, an excellent primate and forest non-profit working in southeast Nigeria and southwest Cameroon. They invited me to stay at their “ranch” to help care for orphaned chimpanzees and drill monkeys. After several months on my own in Africa and having lost 20 pounds, looking after cute young chimpanzees and eating real food (Liza is a great cook) was a refreshing and welcome opportunity.

John-O in the Afi Mountains in 1992. |

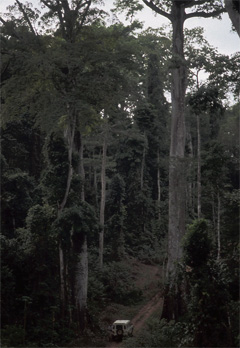

Peter and Liza fed me enough hearty dinners to restore some weight. In exchange I diapered sick and remarkably manipulative young chimpanzees and hand-fed palm-size infant drills that looked like miniature aliens. All the primates cared for by Pandrillus, orphans of the bushmeat trade, get medical care and live with same-species friends in enormous enclosures. After a few weeks of rest and volunteering, I decided to leave my simian friends and continue my jaunt through Africa. Peter and Liza suggested that if I wanted to see a rainforest, I should go to the Afi Mountains, a few hours’ drive north. The Afi Mountains marked a major frontier of deforestation. To the west there were few forests left; most had been cut to feed Nigeria’s growing rural population. To the east, toward Cameroon, there were still plenty of forests, though they too were being exploited fast. Nigeria’s Afi Mountains had key outposts of chimpanzee, gorilla, and elusive drill monkey populations. I caught a lift to the village of Buanchor , a relatively remote village of the Boki tribe. Buanchor, nestled under the Afi mountains, was a colorful and rowdy town, with dozens of chiefs, all whom wore red hats.

The Jeep ride into the Afi Mountains in 1992. Photo by John O. Niles. |

The next morning, having hired guides and met some of Buanchor’s chiefs, I journeyed into my first rainforest. I hadn’t taken more than a few steps into the forest when I stopped, threw off my pack, and then just plain threw up. Months of dysentery and amoebas, some palm wine the night before and a breakfast of fried yams and kola nuts took their toll. The guides were clearly curious about this hairy white guy losing his guts within minutes of what was to be a several-day excursion. Despite my flawed first yards in a rainforest, after a few days of trekking around the majestic and primitive mountains, I was hooked. The rainforest was disorienting, amazing, and completely wild and strange to this Vermonter. The sense of adventure sneaking through a jungle and stalking distant ancestors is beyond description. During the day the jungle’s air glowed green. At night unseen animals joined together in a cacophony of wild sounds that rose and fell in a disorienting and muddled unison. There was a religious sense of awe from the intertwined trees that towered above me. We spent a few days scrambling up and down mountains, calling to attract duikers (small African antelope), reading animal clues, and eating sardines and hard bread in caves. It was during a lunch break, when I heard my first stories about Udoga, a famous hunter who wore only a loin cloth and caught everything from bush rats to gorillas.

Since that fateful trip to the Afi Mountains, I have spent most my life trying to do something positive for tropical forests. This has included several return trips to Nigeria (where I lived with a growing ranch of chimpanzees and worked beside the former hunter Udoga), as well as writing academic articles, helping diplomats, leading an effort to create global forestry projects standards, and starting a non-profit to support forestry projects in post-conflict zones. And this year, for the first time in decades, I have a sense of hope.

The world seems to finally recognize the severe human and environmental costs of tropical deforestation. Ambitious plans are being assembled to provide massive new support for tropical countries to rein in the devastation.

Tropical Deforestation

The village of Buanchor, Nigeria, underneath the Afi Mountains. Photo by John O. Niles. |

Every year, tens of millions of acres of tropical forests are destroyed. This is the most destabilizing human land-use phenomenon on Earth. Tropical forests store more aboveground carbon than any other biome. They harbor more species than all other ecosystems combined. Tropical forests modulate global water, air, and nutrient cycles. They influence planetary energy flows and global weather patterns. Tropical forests provide livelihoods for many of the world’s poorest, most marginalized people. Drugs for cancer, malaria, glaucoma, and leukemia are derived from rainforest compounds.

Despite all these immense values, tropical forests are vanishing faster than any other natural system. No other threat to human welfare has been so clearly documented and simultaneously left unchecked.

Since the 1992 Rio Earth Summit (when more than 100 heads of State gathered to pledge a green future) 500 million acres of tropical forests have been cut or burned. For decades, tropical deforestation has been the No. 1 cause of species extinctions and the No. 2 cause of human greenhouse gas emissions, after the burning of fossil fuels. For decades, a few conservation heroes tried their best to plug holes in the dikes, but by and large the most diverse forests on Earth were in serious decline.

In short, until very recently there has been no concerted effort to tackle what is arguably the most acute threat to Earth’s ecological integrity. Developing countries had other priorities. Conservation can rarely compete financially against putting in a soy bean crop or palm oil plantation, or selling trees, or growing coffee, or raising cattle. Wealthy countries were spending substantially more on toothpaste than on trying to save magnificent tropical forest ecosystems.

A New Plan

Some of the Boki people in Buanchor, Nigeria. Photo by John O. Niles. |

And then in 2005, a small group of countries changed everything. Papua New Guinea teamed up with Costa Rica and a handful of other countries to make a formal plea to the United Nations. Their request was simple—if developing countries can credibly reduce rates of deforestation and the associated CO2 emissions, the countries should get paid. This band of countries, organized as the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, was even more specific. They asserted that tropical nations should get lucrative carbon credits for each ton of CO2 that otherwise would have been emitted because of deforestation. The global market for carbon credits was worth tens of billions of dollars, so tying rainforest protection to carbon finance would raise vast new sums to conserve tropical forests. Since almost 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions are from tropical land-use change, and with growing concern about global warming, other countries began to listen.

Since 2005, the concept of paying countries to conserve their forests and reduce global warming has been dubbed by diplomats as reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries, or REDD. REDD is a bold and evolving plan to radically slow the pace of CO2 emissions by offering hefty incentives for developing countries to stem deforestation. Instead of a couple hundred million dollars per year in conservation charity, billions of dollars in carbon credits could be spent to curtail logging, stop agriculture expansion, or in other ways prevent forests from getting knocked down or set on fire.

|

REDD is also an incredibly risky gamble. The whole plan relies on resolving gaping problems in forest tenure and governance, technological capacities, and regulatory oversight. In many countries it is not obvious who has rights over a forest. And nowhere in the world are there clear answers to the trickier question of who has rights to the carbon stored in the trees. Another key challenge is the need for a new, uniform way of “interlocking” satellite data with tree measurements taken from forests around the world. We can tell reasonably well from space where and when forests are cleared. Not so well understood is how much carbon is stored in a particular forest and how much is oxidized upon deforestation. In addition to issues of rights and technologies, new global institutions are needed to make this REDD plan work. And even with all these pieces in place, REDD assumes that appropriate price signals for saving trees will make a real difference on the ground in forest communities. This is a huge leap of faith, given that many developing countries currently deforesting have only loose control over vast areas of their land. There are also huge political differences about the ideal way to design a new REDD system of forest conservation payments.

What is amazing is that, despite these challenges, some of the brightest conservation minds on the planet, and most governments, now believe that this so-called REDD plan is the best shot for saving millions of acres of tropical forests. REDD has inspired a whole new cadre of optimistic, creative, and determined people who are self-organizing to stop tropical deforestation. Non-profits, forest communities, governors, presidents, consultants, and scientists are working to usher in this ground-breaking plan for saving rainforests. Others are equally determined to prevent a REDD fiasco, citing the problems already noted with particular concerns about REDD’s impact on indigenous peoples and on the global price of emitting carbon dioxide.

|

But for now, the overwhelming momentum points to several new policy mechanisms that would pay developing countries that can demonstrate credible drops in deforestation rates and carbon emissions. The idea of using carbon finance to pay for reductions in deforestation has been introduced in United States legislation (in a bill that passed the House of Representatives as well as in earlier Senate bills) and in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In other words, REDD proposals are moving ahead in the two mega-forums that matter when it comes to climate change policy. What is left to decide now are the details. As in all things, the details will make a huge difference as to whether REDD will succeed or fail.

My future Mongabay.com commentaries will investigate the details, disagreements, and developments of emerging REDD policy proposals. I’ll also explore how the concept of REDD got started in the “voluntary carbon” markets and how proposed policies could dramatically hurt or help these early efforts to make saving tropical forests more profitable than tearing them down. With the United States and the United Nations scrambling to complete new agreements to limit greenhouse gas emissions, this year will be monumental for climate change and tropical forests, one way or another. So far, the signs are dramatically positive but there are many obstacles yet to overcome.

|

John-O Niles is the Director of the Tropical Forest Group, a non-profit that “catalyzes policy, science and advocacy to conserve and restore the planet’s remaining tropical forests.”

This is the first in a series of tropical forest policy commentaries John-O Niles will be writing for Mongabay.com leading up to the December U.N. climate meeting in Copenhagen. |