Failure to develop policies that account for emissions from land use change will lead to widespread deforestation and higher costs for addressing climate change, warn researchers writing in the journal Science.

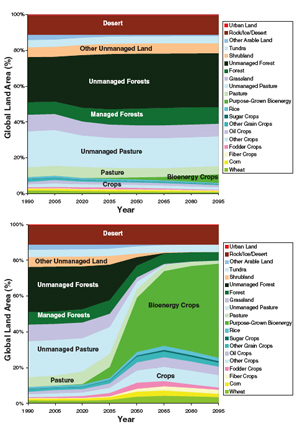

Using a computer model that incorporates economics, energy, agriculture, land-use changes, emissions and concentrations of greenhouse gases, a team of researchers from the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and the University of Maryland found that efforts to limit atmospheric carbon dioxide levels while ignoring emissions from terrestrial sources would lead to nearly a complete loss of unmanaged forests by 2100, resulting largely from increased expansion of bioenergy crops. Meanwhile placing a value (“tax”) on terrestrial carbon emissions equivalent to that on industrial and fossil fuel emissions would lead to an increase in forest cover.

“When society tries to limit carbon dioxide concentrations, if terrestrial carbon emissions aren’t valued but fossil fuel and industrial emissions are, economic forces could create very strong pressures to deforest,” said study leader Marshall Wise of PNNL.

Deforestation for palm oil production in Indonesia |

The results lend support to the current push to include terrestrial carbon sources — forests, peatlands, and other carbon-rich ecosystems — in a future climate framework. The initiative, known as REDD for “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation”, is currently under debate ahead of December’s United Nations climate meeting (UNFCCC) in Copenhagen. While many of the details still need to be ironed out, supporters of REDD say the concept could help save global forests while protecting biodiversity, offering sustainable livelihoods for rural populations, safeguarding important ecosystem services, and helping avoid dangerous climate change.

“The results from this integrated assessment study show that if terrestrial carbon emissions are valued equally with carbon emissions from energy and industrial systems in a regime designed to limit atmospheric CO2 concentrations, there are wide-ranging differences from the case where only carbon emissions from energy and industrial systems are valued,” they write. “Deforestation is replaced by afforestation, crop prices rise, purpose-grown bioenergy becomes an important agricultural product, and people shift away from consumption of beef and other carbon-intensive protein sources.”

The results also demonstrate the importance of relatively high prices for emissions from terrestrial carbon sources in providing an incentive to preserve forests and other ecosystems. Presently credits for “avoided deforestation” are limited to voluntary carbon markets where they fetch only a fraction of the price seen in the E.U.’s compliance market for industrial emissions. The authors suggest that setting a price for terrestrial carbon on par with that for industrial sources would reduce the overall cost of curtailing emissions.

“The total cost of limiting atmospheric CO2 concentrations is reduced, relative to an alternative regime that prices only fossil fuel and industrial carbon emissions.”

The authors also say that agricultural productivity should not be overlooked in policies to mitigate climate change. The show that improvements in agricultural yield to make best use of available farmland will be critical to controlling carbon emissions in the future.

Terrestrial systems store 2000 petagrams of carbon in soils and vegetation worldwide but degradation and conversion of forests, peatlands, and other ecosystems account for more than 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions — a source larger than all the world’s cars, trucks, ships and planes combined.