Putting a price tag on carbon dioxide emissions resulting from various land use practices could dramatically change the way that land is used, including reducing deforestation and limiting agricultural expansion on carbon-rich lands, said a researcher presenting at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“Without valuing the carbon in land, we risk losing large swaths of unmanaged ecosystems to agricultural crops and biofuels,” said Leon Clarke of the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a collaboration between the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the University of Maryland.

Speaking Friday, Clark said that if climate policy aims to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions, it must factor in all sources of emissions, including those from land use. Land use — including deforestation, degradation of forests and other ecosystems, and agriculture — accounts for roughly one-third of global emissions. Such emissions can be reduced through processes that enhance soil carbon as well as reforestation and cutting deforestation.

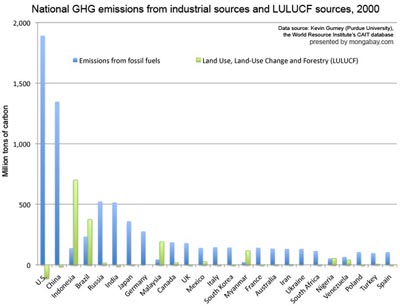

National GHG emissions from industrial sources (electricity generation, transportation, buildings, etc) and LULUCF, 2000. Note that some countries have negative emissions from LULUCF meaning they these sources are a net carbon sink. |

“To limit atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, improving technology for growing crops is potentially as important as energy technologies such as carbon capture and storage,” said Clarke.

Clark’s presentation touched on a delicate question that is still unresolved: how will climate policy address emissions from land use? The U.N. and other entities are presently evaluating mechanisms that would compensate developing countries for reducing emissions for deforestation but some conservationists fear that these policies will be used by agroindustrial firms and forestry companies to subsidize their operations. Since there is presently no “penalty” for their emissions, they may continue to clear and convert forest lands but seek carbon credits for blocks that may be left undeveloped due to their unsuitability for agriculture or timber harvesting. A price on all emissions would be a step towards addressing this concern since companies would have to pay for the emissions associated with all of their activities, but will be strongly opposed by industry. Still as Clarke noted, such a model could be one of the most cost-effective means to curtailing greenhouse gas emissions.

Related

Biofuels can reduce emissions, but not when grown in place of rainforests July 22, 2008

Biofuels meant to help alleviate greenhouse gas emissions may be in fact contributing to climate change when grown on converted tropical forest lands, warns a comprehensive study published earlier this month in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

Reduced impact logging can save 160 m tons of carbon emissions per year August 6, 2008

Improving inefficient logging practices could significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from forest degradation, argues a new study published in the open-access journal PLoS.