Economic downturn may slow — or at least delay — deforestation

Plunging commodity prices may offer a reprieve for the world’s beleaguered tropical forests.

The global economic downturn has caused demand for many commodities to plummet. The resulting decline in the prices of timber, energy, minerals and agricultural products may do what conservationists have largely failed to achieve in recent years: slow deforestation.

Fueled by surging demand from China and other emerging economies, and boosted by the convergence of food and energy markets in response to American and European incentives for biofuels, the worldwide commodity boom over the past few years helped trigger a land rush that precipitated the conversion of natural forests into farms, plantations, and ranches. At the same time, high prices for metals, fossil fuels, and other industrial resources drove a global search for exploitable reserves, many of which lie in tropical forest countries.

U.S. consumption of corn to supply domestic ethanol production created a global corn frenzy which drove up prices and spurred expansion of croplands around the planet. Two examples are Brazil and Laos. Brazil increased production of soy to essentially make up for soy acreage lost to corn in America. In Laos (pictured), returns from corn were so high that Vietnamese traders pressured national park officials to open up protected areas in parts of the country to corn fields. They refused. |

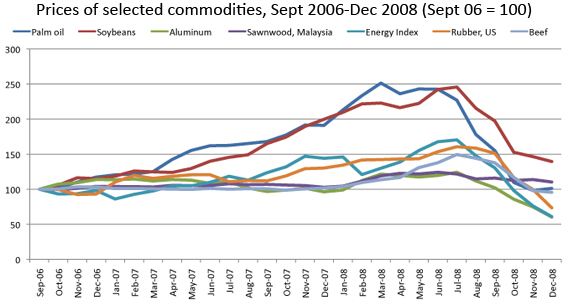

Now that the bonanza is unwinding, with prices for everything from palm oil to bauxite to crude oil cratering, the incentives to clear forests are retreating. Developers large and small are abandoning projects and forgoing planned expansion of existing around the world.

For example in the Brazilian Amazon, where deforestation is increasingly driven by industrial agriculture and ranching, falling grain prices early in the year coincided with a sharp slowing in deforestation. As food and fuel prices peaked through late 2007 and early 2008, it appeared that Amazon deforestation would climb to levels not seen since 2005 — more than 15,000 square kilometers were expected to be lost. The sudden downturn changed all that. When the final numbers came in for 2008, they showed that deforestation only increased a modest 3.8% to 11,968 square kilometers.

The story is similar in the timber sector: the bursting of the property bubble and associated financial crisis has triggered falling demand from consuming countries is forcing producers to scale back operations. According to the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), prices of Malaysian wood products have experience the steepest decline since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, while exports for the Brazilian state of Pará declined 35 percent for 2008. Stockpiles of wood products are building in Indonesia, Malaysia, and China, which experienced a rare drop in the total import and export value its forest products trade in 2008. E.U. imports from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana have slowed since late 2008.

In southeast Asia, a dramatic collapse in the price of palm oil (60 percent off its peak in March 2008) and rubber (down 54 percent from its high in July 2008) is causing a shake-out in the plantation sector, which has become one of the leading drivers of deforestation in the region. Firms operating in Indonesia also appear to be slowing acquisition of forest land for new development.

Still the downturn is not entirely good news for environmentalists. New funds for conservation and research are drying up as donations dwindle and endowments swoon with stock market turmoil (the Wildlife Conservation Society for example saw its endowment fall 27% in 2008 and faces the prospect of 100% cut in state funding for its New York facilities in 2010). Law enforcement, including park protection and monitoring, may suffer from lack of funding, while “green” initiatives by governments and private entities that are “nice to have” in times of plenty) become an afterthought as the economy sours. The same goes for premium “green” products like certified timber and fair trade coffee — demand is expected to decline as consumers rein in their spending. In places where work is scarce there may be increased pressure on natural resources for subsistence use including fuelwood harvesting and slash-and-burn cultivation. Low prices in the carbon market don’t bode well for nascent “avoided deforestation” projects that would compensate tropical countries for reducing their deforestation rates, nor do low oil prices support development of low-carbon energy technologies. Finally the current economic climate offers opportunities for still-healthy firms to buy up forest land and assets at a discount from distressed companies and cash-strapped communities, enlarging their resource pools to exploit once recovery — no matter how green environmentalists try to make it — is on the horizon.