How to Save Snow Leopards

How to Save Snow Leopards:

An interview with Dr. Rodney Jackson of the Snow Leopard Conservancy

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 28, 2008

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is one of the rarest and most elusive big cat species with a population of 4,500 to 7,500 spread across a range of 1.2 to 1.6 million kilometers in some of the world's harshest and most desolate landscapes. Found in arid environments and at elevations sometimes reaching 18,000 feet (5,500 meters), the species faces great threats despite its extreme habitat. These threats vary across its range, but in all countries where it is found — Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Nepal, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and possibly Myanmar — the species is at risk. In some countries snow leopard are directly hunted for their pelt, in others they are imperiled by depletion of prey, loss of habitat, and killing as a predator of livestock. These threats, combined with the cat's large habitat requirements, means conservation through the establishment of protected areas alone may not be enough save it from extinction in the wild in many of the countries in which it lives.

Camera trap picture of a wild snow leopard. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Working to stave off this fate in half a dozen of its range countries is the Snow Leopard Conservancy. Founded by Dr. Rodney Jackson, a biologist who has been studying snow leopard in the wild for 30 years, the Conservancy seeks to conserve the species by "promoting innovative grassroots measures that lead local people to become better stewards of endangered snow leopards, their prey, and habitat."

Jackson says that by enhancing livelihoods through sustainable activities like tourism and teaching people techniques to reduce livestock losses to predators, snow leopards can co-exist with humans in areas that are otherwise unprotected.

"Most of the population actually survives outside reserves," he told mongabay.com. "Therefore it is imperative to involve local people as part of the solution."

"We don't want them to bear the burden, obviously, but to make them the stewards of this rich biodiversity."

Dr. Rodney Jackson. Photo by Brian Keating |

Jackson, who has spent weeks at a time hiking across rugged terrain at high elevation just to reach a study site, has been widely lauded for his approach, including winning the 1981 Rolex Award for Enterprise, being featured in the June 1986 National Geographic cover story on his groundbreaking radio-tracking of snow leopards, and being selected as a 2008 finalist for the prestigious Indianapolis Prize, the largest individual monetary award for animal conservation in the world. Jackson has also authored a number of papers and popular articles on snow leopards and currently sits on the IUCN's Cat Specialist Core Group, a panel that determines the conservation status of the world's cat species.

In an October interview with mongabay.com, Jackson spoke about snow leopards and the threats they face; his research and the Conservancy's conservation initiatives; and the use of technology to revolutionize the tracking and monitoring of these elusive cats.

Mongabay: What lead you to snow leopards in the Himalayas?

Rodney with Mongolian biologist Munkhtsog and their sedated, satellite-collared cat in the Gobi Desert. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: That is a long story. I was born in South Africa, grew up in Zimbabwe, and I fully expected that I would be studying African wildlife. I never really dreamed that I'd end up in the Himalaya.

I went to the University of California at Berkley to get a graduate degree and one day I picked up a copy of National Geographic that had the first pictures of snow leopard in the wild. The pictures showed not only the incredible cat, but of course its habitat — the Himalayas. I just thought, “I have got to go to this place.” And that is what happened. I've stayed in the Himalayas ever since; I never went back to Africa.

Mongabay: Working in the Himalayas must present a lot of special challenges for field work, right?

Snow leopard habitat in Pakistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: There are huge challenges with working in the Himalayas, and in our other program sites. There is the elevation — most of my work is above twelve thousand feet and often as high as eighteen thousand feet because that is typically the elevation range of the snow leopard. I find that I am often working in the middle of winter because this is the best time to see this elusive cat since you can track it in the snow and it tends to go to lower elevations. January, February and March coincides with the snow leopard's very narrow mating season.

There are other challenges of course. There is the very rugged topography. The cats live in highly remote areas. In fact, when we did the first radio tracking of snow leopards back in the 80s it took a month to walk to our study area. We had to walk from the Indian border due north into the foothills, through the foothills, into the south slopes and then to the north slopes in the Himalayas near the Tibetan border. Even now many of the places I go are accessible only on foot, sometimes a week's walk.

Mongabay: Do you pack in food?

Herder in Pakistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: We used to pack in all our food because back in the 80s a lot of these communities were totally isolated. They had very little food; in fact they lived in a food deficiency. Now the communications are improving in many areas and they are beginning to grow different crops. We are able to pick up a fair amount of food in most areas. It is a local diet; it can be very restrictive in a sense. They can grow potatoes well, and in the 80s we would buy surplus from local families and make them into curries.

Mongabay: How is your work received when you go into these local communities? Do most people know about you? Or are you still going to a lot of areas where they haven't seen researchers before?

Rodney Jackson: I am often in areas where researchers are a recent phenomena. Many of the researchers tend to be anthropologist types that are interested in the culture, geologists exploring for minerals or oil, or occasionally engineers who are looking into new roads or bridges. In Ladakh, where the Snow Leopard Conservancy-India has been growing from within the community for 8 years, people in nearby areas are asking for SLC's assistance, and we are increasingly expanding our network at the invitation of local communities. And I'm happy to say that other wildlife conservation organizations are beginning to recognize that true community-based conservation is a big key to saving species.

Mongabay: Is the Snow Leopard Conservancy active across the entire range of the snow leopard?

Rodney Jackson: Of the twelve countries that have snow leopards, we are active in China, India, Nepal, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Mongolia, and we support some local conservation activities in the former Soviet Union.

Mongabay: Do you see different threats depending on the country?

Sheep herd in Tajikistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: We do indeed. If you were to classify the major threats to snow leopards, you would say that in the southern part of the range, and maybe on much of the Tibetan plateau, threats are linked with human-wildlife conflict. That mostly arises from the fact that herders in these areas are totally dependent upon domestic livestock — yaks, cattle, cross breeds, sheep and goats. In the summer, the large-bodied livestock like horses are extremely vulnerable to snow leopard predation. Typically what happens is sheep and goats are kept outside in poorly constructed stone corrals. These are great at containing the livestock, but they are not good at keeping snow leopards out. Once the cat gets in, mêlée follows where animals are frantically running around, causing a lot of confusion, and repeatedly triggering the predator's hunting and killing instincts. So at the end of the night you can have thirty, forty, the most we know about is almost one hundred sheep and goats either dead or mortally wounded. That's the equivalent of the entire bank account of one or more households and they get extremely angry and naturally they start wanting to kill the predator and they will poison traps to do so.

That is the problem in the southern part of the range where animal husbandry is really the dominant land use. In the northern part of the range — places like Mongolia or Tajikistan or Kyrgyzstan — although there are livestock, for some reason predation doesn't seem to the be the big problem. What is the more likely problem is humans actually trapping the snow leopards or their prey. They are trapping snow leopards for the pelts to sell on the black market, which is a source of income, or the bones and the body organs which then go to China for medicinal uses, aphrodisiacs and so on.

Mongabay: So it sounds like the conservation approaches would be quite different in the two areas.

Woman boiling milk in Tajikistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy. |

Rodney Jackson: They are but there are commonalities to both the areas. I believe that ultimately wildlife conservation is in the hands of local communities. I say that primarily because there are maybe as many as a hundred protected areas set aside that are thought or known to contain snow leopard. But most of them are extremely small, so they only have enough area or territory for less than a dozen cats, sometimes not even one or two. I believe most of the population actually survives outside reserves, most of which exist largely on paper only. Management is weak or virtually non-existent.

Mongabay: When you work with local communities on things like reducing predation, what are some of the strategies? Are you looking at guard dogs and things of that nature?

Predator-proofed corral in Pakistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: There are a number of strategies that we employ and they mostly go in tandem with cooperative planning involving the local community where we would go into a village and identify what sort of anti-predator strategies they have, how these can be refined, and then come up with a solution that meets not only conservation needs but local livelihood needs. The communities almost invariably recognize that their guarding of livestock is not very good. They either lack sufficient labor — people out there all the time — or they lack the materials for making the enclosures predator-proof. So one strategy is to work with all members of the community, including elders and women, to develop a collaborative plan. They provide the stones and the labor to predator-proof a corral and we provide wire mesh to put up on the roof, doors and windows so it is secure — so a predator cannot get inside the structure and cause such havoc. That is one approach. That would help eliminate the incidence of multiple killing, where you lose more than a few animals at a time and creates so much anger from herders. It will not eliminate all predation. These herders will continue to lose livestock on the open pasture, one or two at a time, to carnivores – not only snow leopard but also wolves, fox, lynx, and wild dog.

A predator-proofed corral in Matho village in Hemis National Park, Ladakh. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

In addition to preventive measures, we work with communities to identify incentives whereby they can better afford to coexist with large predators. Those typically involve activities that improve their income so that if they lose one or two sheep it is not so critical to them. They can replace them as commodities if they have the cash.

One of our most successful incentive programs is called Traditional Himalayan Homestays in northern India. It is basically a “Bed & Breakfast” operation where people set up accommodation for visitors in a spare room. Tourists are encouraged to spend the night and have a communal meal in the kitchen with the family and learn something about the culture. Each tourist pays about $10 a night, including three meals. It's a lot of money in that economy.

Mongabay: There is enough interest from tourists to make that viable?

Home stay. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: Well, there is. The way this grew up — it actually wasn't our idea at all, it was a local woman's idea, which was echoed by many villagers in one of our planning meetings. There are trekkers that hike independently in Ladakh and basically go from village to village. They don't carry their own food or their own tents so the local people started catering to them but didn't have formal training in accommodating visitors. The villagers were not sure what kind of food to provide, they weren't sure of the hygiene and all that kind of thing. So Snow Leopard Conservancy-India provides one or two weeks of training on how to operate a Homestay, how to maintain good standards, and what kind of food they should offer — local of course so they don't have to invest their money in foreign foods. Homestays are all managed by a women's group in each village. We do facilitate marketing with travel agents, and I believe that some groups have even asked the agencies to build a Homestay in their trip. In 2005, Himalayan Homestays were awarded Travel+Leisure's Global Vision Award, and the World Travel Market First Choice Responsible Tourism Award.

Bachor Women’s meeting in Tajikistan. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

In each community not everybody can qualify to have a Homestay because maybe they don't have a big enough house or maybe they don't have enough family members to manage it. But those that do we put on a rotational basis, so that over the summer season, the busiest time, every household will get an opportunity to have a visitor. You won't get a situation where one or two households won't have any visitors, or where others are more active and one family captures most of the business.

Mongabay: Are you looking at broader livelihoods, like developing so-called predator-friendly meat products or other things of that nature?

Rodney Jackson: Other organizations are looking at that. For example, the Snow Leopard Trust in Seattle has been working on handicrafts, training people in Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan to produce handicrafts that are airfreighted to the U.S. and sold in zoos and at public events. The income then goes back to the people to pay them for their time and give them a bonus for protecting wildlife. We see no reason to duplicate this effort, the Trust is doing a fine job with it.

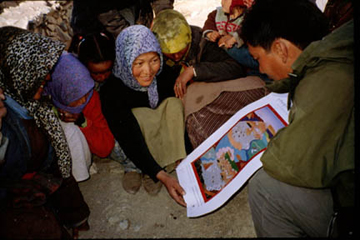

Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

We aim for activities or programs that can be picked up and operated sustainably on a local basis, by local people themselves, where there is no need for foreign input over the long-term. That specifically comes down to ideas that build in an ecologically and culturally responsible way upon existing tourism, keeping in mind that it is a tenuous business, and it may crash at any time due to political upheavals or natural disasters. We have been aiming far at more at dealing with domestic tourists whenever we can. Those are growing in China, India and even places like Mongolia.

Mongabay: Between the different countries where you are active, do you see a big difference in the government support of your efforts?

Rodney Jackson: Yes we do. I would say that countries that are really leading the way are countries like Bhutan. I think Mongolia has been very progressive, although it faces some very, very serious internal problems right now. I think some communities even in a beleaguered country like Pakistan are taking things into their own hands, especially at the community level and the government goes along with them.

Female snow leopard with cubs captured by a camera trap. Photo by the Snow Leopard Conservancy, with assistance from Richard Goold. |

Some countries will place more emphasis on research rather than on direct conservation. Other countries basically feel that research takes money away from conservation and they really put far more emphasis on development activities. A lot of the areas we work in are border areas and sometimes the countries are at war with one another. Most snow leopards live within one hundred miles of an international border.

In almost all the countries where we work, governments would rather see local researchers and conservationists at the forefront than foreign professionals. So would we, and it's actually one of our goals — to build local capacity. But only recently have young biologists come up who have the training, commitment and dedication. And even then these are few and far between.

Mongabay: Do you have members of these communities who end up helping you out as field workers or trackers or staying behind and helping with conservation?

Snow Leopard Conservancy collaborates extensively with in-country conservation and education groups. In Nepal and India, for instance, environmental education, with a focus on the local web of life, is conducted entirely by local education specialists, with minimal oversight and funding from the Conservancy. |

Rodney Jackson: As I mentioned before, trained local professionals are largely lacking, so one thing we try to do to compensate for that is train interested people in the communities, even if they don't have what would be considered the right educational qualifications. But it's a challenge. There is generally an outward migration from the local communities into the city. That is happening because the youth of today have been exposed to television, and foreigners, and nice clothing and so on. They're less willing to live the really hard life of a shepherd. They want more to go into the local town or the administrative center, get a job as a teacher, a government worker, or a soldier. So even if we can find people to hire, after a few years, they go back to the city and start a family there.

From a biodiversity conservation standpoint this exodus might not be a bad thing because it reduces the pressure on the fragile, alpine environment, which has a very low carrying capacity. On the other hand, the down side is that – like globalization in general – it can lead to the erosion of the very rich culture of that part of the world.

Mongabay: Regarding modern changes, it looks like you have some pretty interesting technology that you are applying to your efforts. Can you elaborate on these tools?

Snow leopard captured by a camera trap. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy. |

Rodney Jackson: Sure, there are a couple of technologies I would like to talk about. One is the CyberTracker which is a simple Palm Pilot, a little hand-held computer that has a GPS built into it. It can be programmed with icons to record animal observations with their geographic locations so they can be brought into computers and analyzed. One difficulty we are finding with that technology is that all these little Palm Pilots have built-in batteries that need to be charged by electricity and many, many villagers do not have electricity. So we had to rely on some of the older equipment that uses AA batteries. The problem with that equipment is that its GPS software programs don't work very well in rugged terrain. It would be wonderful if they would manufacture something that would allow you to use the latest hand-held device with it's huge database and storage space while also operating on batteries that you could buy in the local market.

In terms of other technology, I just came back from the Gobi Desert area of Mongolia where we placed a satellite collar on a male snow leopard in late September. The collar is programmed to get a GPS location every seven hours around the clock and we are able to download that information from a secure website. It is almost real time, close to real time anyway, we can know exactly where our cat is and we can follow it from the other side of the world. That is a great technology for learning about snow leopard movement, dispersal patterns, and habitat utilization. Of course it is very expensive.

Local education program at Hemis Shukpachan in India. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy. |

In some countries they are reluctant to provide researchers with permits to live-trap, immobilize, and radio collar endangered species like the snow leopard. Also, it's important to realize that collaring a snow leopard is going to be limited relative to a big animal like an elephant whose much bigger collar can generate so much more information. For snow leopards we hope the collars we can get out there will provide enough data to enable us to make some models for snow leopards that we could then test indirectly through the geographical information — habitat, vegetation and topography maps from an area — and then try to predict how a snow leopard might move through there, how many might be able to survive in an area, what kind of movement through what we might call projected home range they might have, and understand how they go about searching for their prey. All this is really helpful for a species that you never see. I have really only seen this cat maybe once a year in my whole career and I have been working on this for thirty years. So we really have to be innovative about how we go about researching such an elusive creature.

Mongabay: A little different than an African-type safari.

Rodney Jackson: Conservationists in the African Savanna have it so much easier. They can get in their Land Rover and drive to a spot where they know their subject will be on a daily basis and spend the next several hours watching it. You just don't know how unusual that is in the Himalayas. But we are beginning to see the cats much more now in the areas where they are being protected by local communities. Last year I watched one on a hill for maybe 3-4 hours from about 50 yards away; it was an incredible experience. I would hope that one day Asia would have wildlife viewing opportunities that can compete with Africa!

Getting back to your question on new research tools, there is a new technology we are working on with Jan Janecka from Texas A&M University and other partners. I really think genetic analysis holds the key to finding out where snow leopards live, how many there are, what the current distribution is and simple things like number of individuals present in a potential protected area, how many males, how many females, and the family relationships of those individuals. This is non-invasive, powerful work.

Rinchen Wangchuk, director of SLC-India, collecting data at a rock scent-marked by a snow leopard. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

We can take the scat of snow leopard, which is fairly easy to find if you know something about their movement patterns and habitat use. We collect a tiny bit of scat, bring it back to the lab and analyze it genetically. It tells us a lot of information: the cat's identify, its gender and relatedness to other snow leopards in the same terrain. Even three-month-old scat can be used to identify individuals. The technique should give us a good understanding of the number of snow leopards living in the area and their population density, from which we can extrapolate to have a far better handle on the size of the world population. And again, I want to say that the training we are providing local biologists, and the involvement of the herders — in the on-the-ground collection, and followup — means that ownership resides where it should: with the people who share the snow leopard's habitat.

We are still using camera trapping as well. Camera trapping is a little more expensive – you need ten or 15 stations to cover an area and they have to be deployed for 40-60 days to make sure you get an image of every cat there. But they can be very useful. We pioneered the use of camera traps for snow leopard, first in the 80s, and between 2002 and 2003 our team got over 300 images in Ladakh. The most recent place we did it was on an isolated range in Mongolia. We estimated there were four individual adults and three cubs and that actually matched very well with the independent survey using genetics that estimated there were five cats in the area.

Mongabay: What is the current estimate of the world population of snow leopard?

Snow leopard photographed (not camera trapped) by our associate, Som Ale, proving that snow leopards are returning to the Mt. Everest area after a long time. That’s near where Rodney is now, assessing the wildlife corridor. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy. |

Rodney Jackson: The estimate is between four-and-a-half to about seven-and-a-half thousand animals across 1.2-1.6 billion square kilometers. They are very sparsely distributed throughout that area, and I'm sure there are big gaps where they used to be historically, but are no longer present because of illegal poaching, human activity and so on. China occupies something like 60 percent of the total range of the snow leopard, and I am extremely worried about them there. The estimate of snow leopard in China is somewhere between two to two-and-a-half thousand. Well, I seriously doubt there are that many. I have been to now a number of prime snow leopard areas and found very little or no sign of the cat. Spending a four or five days in an area looking for signs I can pretty well tell whether one or two cats are present or not. And we really need more than one or two because they have a very narrow breeding season, it's only about two months of the year, in which that male has to find the female, otherwise you lose the whole year and that animal faces a high probability of being killed in the interim. So this is why some populations are declining rather than stabilizing.

Mongabay: So what's your overall outlook? Is the population stabilizing or is it still declining? Or do you not know?

Camera trap picture of a wild snow leopard. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: We have to consider that question on a country-by-country or region-by-region basis. If we look at the Himalaya, and by that I mean the ranges that run through Nepal, India into Northern Pakistan, I would say snow leopards are generally doing well. The population appears stable overall and in many places is increasing slowly. So the prognosis for the Himalayan countries looks good. Conversely, the prognosis for China, Mongolia, and much of the former Soviet Union countries, now independent republics, does not look very good. Following the break-up of the USSR all of the really good protected areas, as well as sound conservation and protection measures that the Soviets had in place, broke down almost totally. The economy went from a top-down supported economy to a free-market economy in which people had no idea how to generate income except to harvest all the resources in desperation. Poaching was extremely rife and the population of snow leopards in Kyrgyzstan for example declined by almost 90 percent in a few years to the very low level of today. However numbers appear to beginning to recover thanks to the sort of conservation programs that have been so effective in the Himalayan region.

Mongabay: How can people in the U.S. help snow leopard conservation?

Rodney Jackson: Snow leopards really are a world heritage animal that should be treasured, even from half a world away. We need to bear some responsibility in helping other countries preserve them for the benefit of future generations and ecosystem balance. To do that of course we need funding. We offer special Quest for the Snow Leopard trips to northern India. We run them summer and winter. Winter offers the best chance of actually seeing a snow leopard, and I myself spend 10 days in camp with the group, leading the daily search for sign. Anyone who goes on the winter trip needs to be a hardy, experienced trekker willing to snow camp in freezing temperatures. For that privilege, each guest makes a significant donation to the Conservancy! But we have seen cats during each of the past 3 winters, and our guests say it was a life-changing experience. Details are on our website: snowleopardconservancy.org/visitladakh.htm

Our website's Donate and Buy section also has some unique items for sale, including the book Vanishing Tracks: Four Years Among the Snow Leopards of Nepal, by my partner Darla Hillard. It's a behind the scenes account of the years we spent between 1981 and 1984 with our colleagues in Nepal doing the first radio tracking study of snow leopards. The cover story we had in the June 1986 issue of National Geographic helped her find a mainstream publisher, and it's a great read – based on the diary she kept all those years.

Another way to help is by doing a Traditional Himalayan Homestay

And of course we always accept donations in any amount!

Mongabay: Where are you headed next?

Male blue sheep in Ladakh. Photo courtesy of the Snow Leopard Conservancy |

Rodney Jackson: I'm off to Nepal next week. I'll be working in the Mount Everest area. Mount Everest is of course is so well known for the mountain climbers, but beneath those peaks is an incredibly rich biodiversity that includes animals like Himalayan tahr, blue sheep, snow leopard; many, many birds, insects, and reptiles. And their future is totally dependent on protecting a diversity of habitat types and landscapes; which means that we've got to look at things in the bigger picture. We've got to look at corridors and we have to start linking the different types of habitat areas which support sub-populations (or could do so). And that, I think, requires not more parks that are costly to establish, but basically to figure out what local communities can do to enhance their livelihood, while protecting their environment. We don't want them to bear the burden, obviously, but to help them benefit from wildlife conservation and enable them to be the stewards of this rich biodiversity. So our goal now is to go out and do some noninvasive techniques, identify the areas where we need to concentrate our efforts. That’s where conservation activities will be most effective.

The Snow Leopard Conservancy is a partner of the Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), a group that focuses on funding, supporting and developing the next generation of “conservation entrepreneurs”.

Special thanks to Tiffany Roufs for her help putting this interview together.