Planktos kills iron fertilization project due to environmental opposition

Planktos kills iron fertilization project due to environmental opposition

mongabay.com

February 19, 2008

Planktos, a California-based firm that planned a controversial iron-fertilization scheme in an attempt to qualify carbon offsets, announced that it failed to find sufficient funding for its efforts and would postpone its project indefinitely.

The announcement came as welcome news to environmentalists who feared the plan would be damaging to marine life. Planktos had planned to dump tons of iron dust in waters near the Galapagos islands.

Planktos claimed it was a victim of “a highly effective disinformation campaign waged by anti-offset crusaders… [which] caused the company to encounter serious difficulty in raising the capital needed to fund its planned series of ocean research trials.” Scientists questioned whether the firm would be able to quantify carbon sequestration from its efforts, while the U.S. government ruled that the experiment would violate ocean dumping laws. Planktos intended to use foreign vessels to skirt the U.S. Ocean Dumping Act.

Citing research showing links between wind-blown iron dust and photosynthesizing-microorganisms known as phytoplankton, Planktos believed artificial iron fertilization would trigger massive blooms of phytoplankton that would absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and help fight global warming. The firm would then sell the carbon credits to individuals and companies looking to offset their greenhouse gas emissions.

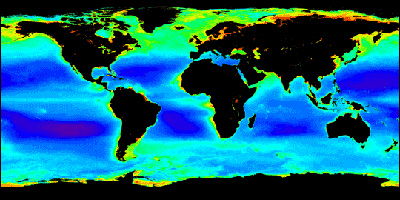

This SeaWiFS image shows average chlorophyll a concentration from October 1997 to April 2002. Image courtesy of the SeaWiFS Image Gallery |

Scientists — including researchers at Stanford and Oregon State Universities — said that any bloom of phytoplankton induced by Planktos would be accompanied by a bloom in bacteria as phytoplankton die. These bacteria may produce gases–like nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas–that counteract the effects of carbon sequestration by phytoplankton. Further, bacterial decay consumes oxygen, which alters water chemistry.

“Ocean fertilization schemes… may not remove as much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as has been suggested,” said Dr. Michael Lutz, now at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “The limited duration of previous ocean fertilization experiments may not be why carbon sequestration wasn’t found during those artificial blooms. This apparent puzzle could actually reflect how marine ecosystems naturally handle blooms.”

Environmental group WWF also warned that the introduction of large amounts of iron to the ecosystem would likely be accompanied by other trace metals that would be toxic to some forms of marine life.

“World Wildlife Fund’s concern extends beyond the impact on individual species and extends to the changes that this dumping may cause in the interaction of species, affecting the entire ecosystem,” said Dr. Sallie Chisholm, microbiologist, MIT and board member, World Wildlife Fund. “There’s a real risk that this experiment may cause a domino effect through the food chain.”

“There are much safer and proven ways of preventing or lowering carbon dioxide levels than dumping iron into the ocean,” said Dr. Lara Hansen, chief scientist, WWF International Climate Change Program. “This kind of experimentation with disregard for marine life and the lives of people who rely on the sea is unacceptable.”

Related articles

Shell Oil funds “open source” geoengineering project to fight global warming

(07/21/2008) Shell Oil is funding a project that seeks to test the potential of adding lime to seawater as a cost-effective way to fight global warming by sequestering large amounts of carbon dioxide in the world’s oceans, reports Chemistry & Industry magazine.

Geoengineering could stop global warming but carries big risks

(6/4/2007) Using radical techniques to ,engineer, Earth’s climate by blocking sunlight could cool Earth but presents great risks that could well worsen global warming should they fail or be discontinued, reports a new study published in the June 4 early online edition of The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.